Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

In his third annual State of the City address last Thursday, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio put forward a $2.5 billion dollar plan to install a public transportation project connecting Brooklyn and Queens along the waterfront. The plan did not propose the incorporation of new buses or subways, instead he wants to bring the streetcar back. Here’s a recap of the history, plans, pros and cons of the streetcar plan.

It was the end of October 1956 when the last three trolley lines in Brooklyn were finally decommissioned by the city. Since then the notion of streetcars in New York City has been long forgotten by the city’s residents and local government, apart from the abandoned trolleys that once sat on the Red Hook waterfront. New York City was at one point bustling with streetcars not just in Brooklyn but also in Manhattan and Queens. At its peak the city’s complex streetcar system had over 100 lines, but the initial success of overground transport didn’t last long.

New York Railways, a private company invested in most of the city’s streetcar infrastructure and it could not compete with its rival National City Lines. National City Lines owned the majority of buses in the city. During a time of increased investment in oil and automobiles, it gained a competitive advantage. New York Railways had pledged to charge its customers a toll of just a nickel, but with rising operating costs and economic downturns the company went bankrupt. Streetcars in New York City remained predominantly a distant memory until last week when the city announced plans for a new Brooklyn-Queens streetcar route (BQX).

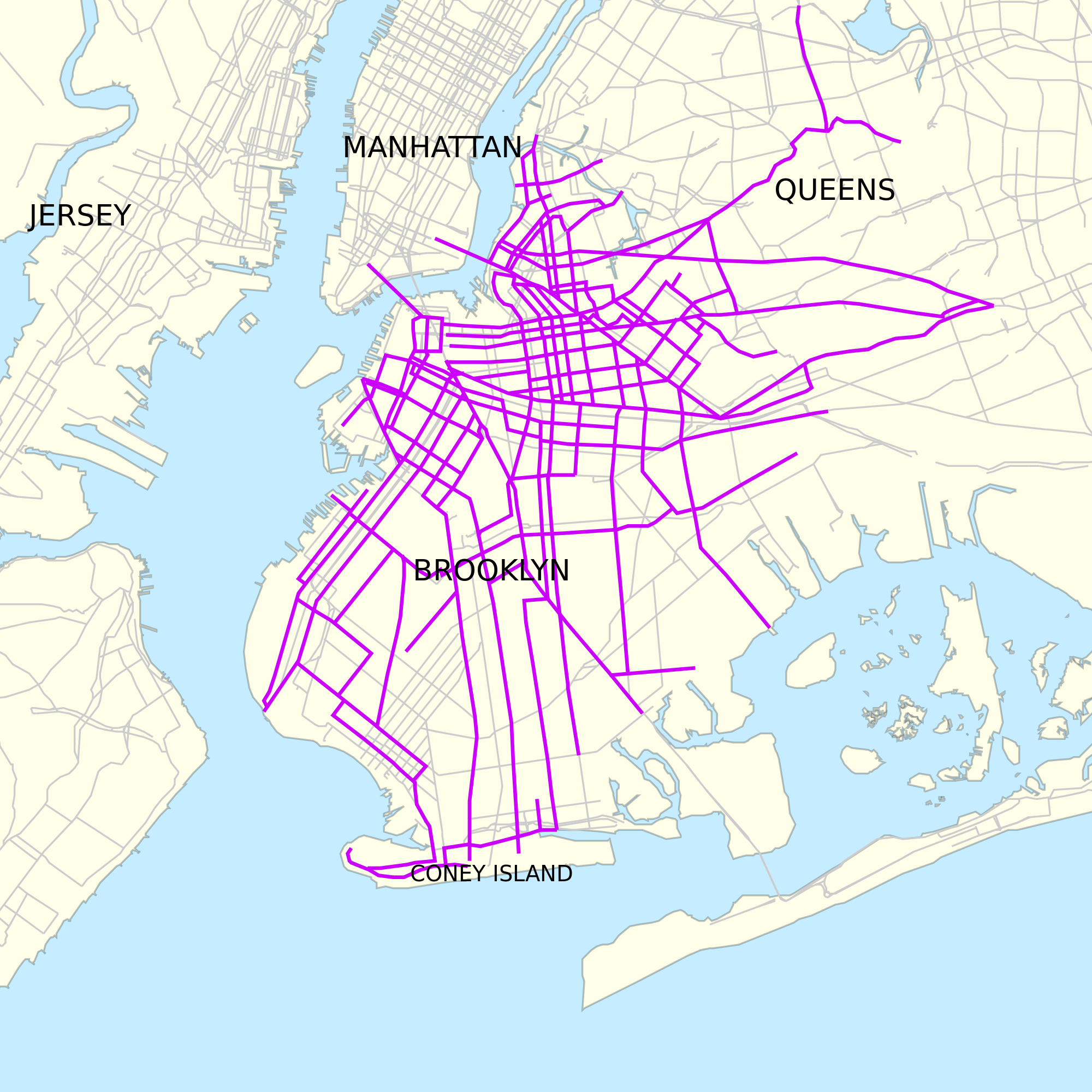

Original streetcar line that ran through Queens and Brooklyn connected the two boroughs, and Manhattan. Map in creative commons from Sharemap.

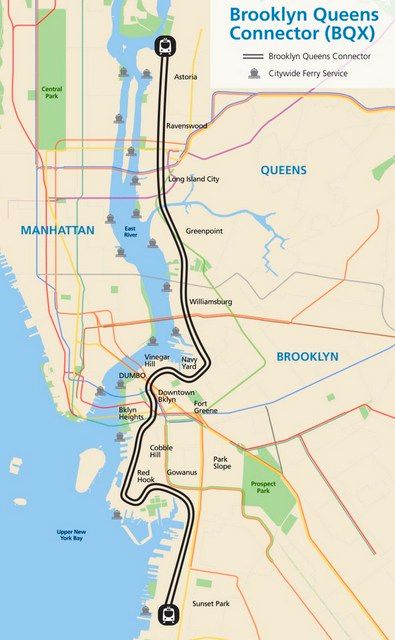

The sixteen mile plan with Sunset Park at beginning of the line and Astoria at the end.

In his annual State of the City speech, Mayor de Blasio spoke enthusiastically about his effort to reimagine the city’s waterfront and proposed the reinstallation of a whole new modern fleet of streetcars. Dubbed the Brooklyn-Queens Connector (BQX), the streetcar line would run from Sunset Park to Astoria, along the waterfront. The new overground system would traverse transportation-starved communities like Red Hook, which has long been cut off from the rest of the city’s vast transit system, along with underserved areas with forthcoming city-backed development plans such as the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Sunset Park waterfront.

Instead of taking detours or traveling in and out of Manhattan, passengers will be able to travel from Red Hook to Long Island City in about 25 minutes compared to the 45 minutes to an hour it would take via subway, or from Greenpoint to DUMBO in about 27 minutes. The trolleys would travel at about 12 miles per hour.

If approved, construction would begin in 2019 with service starting in 2024 at the earliest. A detailed plan of the route has yet to be published, but officials stated that the streetcars would travel periodically, both on the same roads as cars as well as in separate lanes with physical barriers between the streetcar and other forms of traffic.

Image from Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector

The Mayor made it clear that streetcar plan specifically targets neighborhoods undergoing significant development, either ongoing or forthcoming such as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Sunset Park and Long Island City. With more residents and businesses coming to the Brooklyn waterfront through planned development and real estate speculation, improved intra/inter borough transportation is clearly necessary, and the city expects that a rail line will spur further investment in these neighborhoods. Richard Ravitch, former Lieutenant Governor of New York and Chairman of the MTA commented, “The more mass transit we have, the better off we are as a city that is growing.”

In addition, the streetcar line would also relieve pressure on subway lines in Manhattan, taking out commuters who are currently forced to travel into Manhattan just to get elsewhere in Queens or Brooklyn. As Alicia Glen, current Deputy Mayor for Housing and Development explained, “The old transportation system was a hub-and-spoke approach, where people went into Manhattan for work and came back out…This is about mapping transit to the future of New York.” With the L train potentially facing a long-term closure on part of its line, the BQX could also serve as an auxiliary or relief line.

The BQX has received significant support from the private sector as well. Fred Wilson, venture capitalist and co-founder of Union Square Ventures shared the Mayor’s optimism saying, “This is a big deal for NYC and a big deal for the NYC tech sector…Fixing the transportation problems into these developing neighborhoods will bring people and jobs and new vitality to these waterfront neighborhoods.” Another endorsement came from Jed Walentas, developer and founder of Two Trees, the firm behind the revitalization of DUMBO and the Domino Sugar Factory project in Williamsburg. He praised the Mayor’s new plan and even offered to pay for a study to determine the exact cost of the project.

Rendering of streetcar on its way to the Atlantic Terminal near Barclays Center in Brooklyn. Image via Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector

Many questions and criticisms have risen about the Brooklyn-Queens Connector. The $2.5 billion cost is cheaper than digging a new subway line, but some argue that the money may be more effectively used to improve the existing bus system. Funding, according to the Mayor’s office, would come from tax revenues derived from increasing property values in the area.

Another critique has been the streetcar system’s vulnerability to environmental disaster, particularly given the alignment of the streetcar path with the flood zone and damage sustained by the Brooklyn waterfront during Hurricane Sandy. Some areas were without power for two weeks and it took over a year before vital infrastructure in the region was fully restored. With the inevitability of future superstorms, it seems necessary to institute a concurrent plan to protect the streetcar line but a recent $176 million dollars award for a new flood protection program will only cover the lower part of Manhattan. A revitalized flood barrier has not been implemented along the East River and members of the Red Hook community will likely face more damage if another storm were to take place.

The approval process will also likely be ripe with controversy. On one hand, the streetcar will not run on any land that necessitates state jurisdiction, thereby removing any approvals from Governor Andrew Cuomo. But the project will require the approval of local community boards, institutions generally and traditionally hesitant about change, in the standard ULURP (Uniform Land Review Procedure) process. Benjamin Kabak of Second Avenue Sagas contends that this makes the proposed timeline “aggressive.”

For now, we’ll let time and politics hash out the future of the New York City streetcar project.

Next, check out 5 proposed transportation projects that may change NYC and see renderings of MTA’s Open Gangway Prototype Subway Cars for NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter