Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

New York’s history has included everything from transit strikes to riots over Shakespeare to immigration from nearly every country in the world. Yet, for much of this history, people didn’t always know the “correct” time or date. Until 1883, virtually every place in the country set local time according to the sun. According to Sam Roberts in his book Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America, “Typically, noon would be regularly signaled so people could synchronize their clocks and watches.” From dropping a ball down a flagpole in Manhattan to ringing a gong, settlements all across the country would alert people of noon. But as railroads spread throughout the country, it was nearly impossible to standardize the time.

“A passenger traveling from Portland, Maine, to Buffalo could arrive in Buffalo at 12:15 according to his own watch set by Portland time,” Roberts writes. “He might be met by a friend at the station whose watch indicated 11:40 Buffalo time. The Central clock said noon. The Lake Shore clock said it was only 11:25. At Pennsylvania Station in Jersey City, New Jersey, one clock displayed Philadelphia time and another New York time. When it was 12:12 in New York, it was 12:24 in Boston, 12:07 in Philadelphia, and 11:17 in Chicago.”

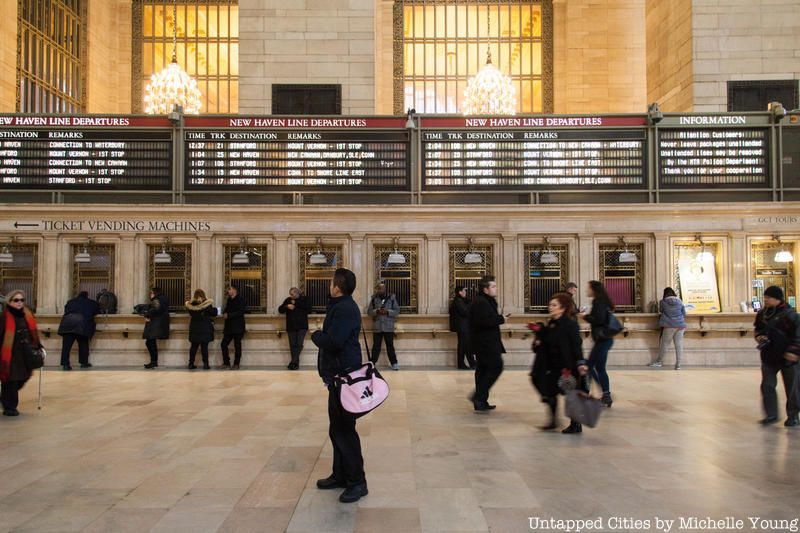

The former Grand Central Departure Boards, now replaced with digital screens

This was not the first time the country had an issue concerning the standardization of time. Over a century before, New York and other British colonies standardized the calendar by losing an entire 11 days. From 1582 to 1752, Europe had two calendars in effect at the same time, the Julian and Gregorian, and both had different starts of the year. The Julian New Year would begin on March 25, yet the Gregorian New Year would begin on January 1. England and its colonies decided in 1752 to change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, yet the discrepancy between a solar year and the Julian Calendar was 11 days out of sync. The legal new year was switched from March 25 to January 1, and 11 days were dropped from September 1752.

Despite losing 11 days, this transition did little to standardize the time in the states. The invention of railroads contributed a little to these time differences, as train whistles were significantly louder than a gong or ball drop, dropping the number of local standards from over 100 to about 53. Yet, while Greenwich Mean Time was adopted by the British in 1848, the states made little progress in adopting a more orderly time system. Amateur astronomer William Lambert proposed a standardized time system to Congress in 1808, but little was done for nearly 80 years.

The five time zones in New York City (found in the NYC Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning & Sustainability in 2011). Photo by Michelle Young/Untapped New York.

Inaccurate times led to a number of fatal crashes in the Northeast in 1853, yet Congress took little action and authorized the building of the transcontinental railroad, which led to even more collisions. A proposal for multiple time zones was first proposed by Reverend Charles F. Dowd, who proposed four zones 15 degrees longitude-wise. On Sunday, November 18, 1883 this proposal was embraced by the General Railway Time Convention, and now people in each time zone operated on the exact same time. Strangely, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit refused to comply, and Cincinnati delayed the new time’s implementation for a few years.

195 Broadway. The building that now stands here was built from 1912-1916.

According to Roberts however, “In New York, they would strike noon approximately 3 minutes, 58 seconds, and 38 one-hundredths of a second earlier than they had the day before.” The official timekeeper prior to this change was the Western Union Company at 195 Broadway in Room No. 48. James Hamblet, the superintendent of Time Telegraph Company stopped the regular clock at 11:00, paused for 3 minutes and 58 seconds, and started it again at standard time. The first noon under this new time was signaled by the dropping of a copper time ball from a 22-foot-tall staff on the Western Union Building. Funnily enough, the bells of one church rang 3 minutes and 58 seconds earlier than the new standard time on November 18, 1883, so New York had two noons that day after the copper ball fell.

Grand Central actually was the first railroad station in the nation to adopt standard time, stopping the regulator clock at 9:00 a.m. Grand Central’s master clock is currently found on the Lower Level by Track 117, synchronized every second by a signal from an atomic clock at the Naval Observatory in Bethesda, Maryland. The builders of Grand Central carved “Eastern Standard Time” into the marble under the master clock to commemorate the station’s role in implementing time zones. This master clock controls the time at every other official clock in the terminal. But until 2004, before the clock was synchronized to the atomic clock, the clocks in Grand Central often contradicted each other — even the four clock faces on the information booth didn’t have the same time. Today, the clock one in the Graybar Passage is still sometimes inaccurate!

Book a future in-person tour of Grand Central Terminal (or take a virtual tour!)

Next, check out The 1966 Transit Strike That Paralyzed NYC For Almost Two Weeks!

Subscribe to our newsletter