Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Con artists were no strangers to early New York City. At one time or another, nearly every major landmark in the city had been sold by a ‘matchstick man.’ Around the turn of the twentieth century, one such fraud was performed by two men who targeted an artifact of slightly less renown: The Great West Point Chain.

The Great West Point Chain was the linchpin of the American defenses at West Point during the Revolutionary War. Prior to the Chain, various other methods of securing the Hudson River Valley from invading British vessels had been tried, but none with success. First installed across the Hudson at West Point in 1778, “General Washington’s watch chain” would guard the River for four years.

George Washington contracted Sterling Iron Works to make the chain, according to the Office of the USMA Command Historian. It contained 750 links weighing 100-120 pounds each. The chain was pulled out of the river each fall so it wouldn’t break when the water froze in the winter. The ice would keep the British at bay during that time. The chain was reinstalled each spring for four years. It was taken in for the last time in the fall of 1782.

After the War, the Chain was left on the riverbanks. The new country was nervous that they would end up in another war with Great Britain and didn’t want to dispose of the Chain in case it became useful again. However, when war did break out again in 1812 the Chain sat idle. Finally, in 1829, it was melted down.

Or so it seemed. Over the next 60 years most forgot about the West Point Chain. Then, in 1889 Chicago confectioner Charles Frederick Gunther began displaying 18 links of the “original” West Point Chain in his curiosity museum. He had bought them from a military surplus dealer in New York City.

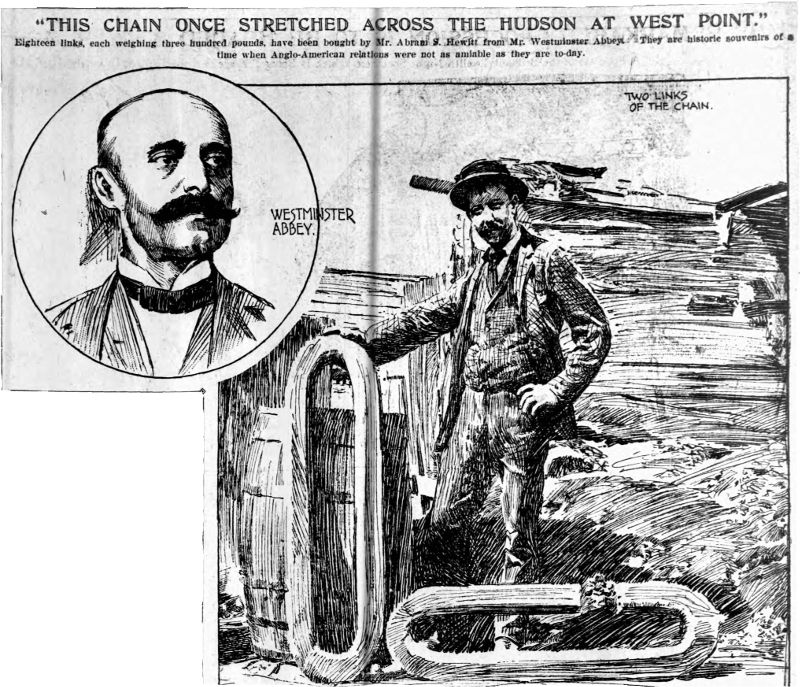

The dealer went by the unlikely moniker of Westminster Abbey (he told people his father had wanted him to be a lawyer and gave him a distinguished name. This would probably have given his father quite a shock, as the elder Abbey actually named his son ‘John’). ‘Westminster’ ran a junk shop on Front Street near the South Street Seaport, advertising everything from “rifles, revolvers, and military pistols” to the “best mixed tea, wholesale or retail”.

Abbey picked up his chain at an auction at the Brooklyn Navy Yard but didn’t pretend to know how it got there. When asked, he simply replied that Gunther had verified it. Abbey hit the jackpot, both in dollars and publicity, when he managed to sell 18 links of the chain to former New York mayor Abram Hewitt in 1898.

Abbey got out of the chain game shortly after the Hewitt sale. He sold his remaining sections to equally dubious (albeit more successful) surplus dealer Francis Bannerman VI, of Bannerman Castle fame. Where Abbey was an amateur self-promoter, Bannerman had gone pro. To go along with his links (and the desk weights he made out of some pieces) Bannerman printed up a booklet detailing the chain’s history.

According to Bannerman, a large section of the Great Chain had survived the furnace and was brought to Manhattan in 1864 to be displayed at the Metropolitan Sanitary Fair, which raised money for the Union Army. Rather than haul the Chain back to West Point after the fair, it was dumped in Brooklyn. It had been Bannerman’s father (also a surplus dealer) who bought the chain at the Navy Yard Auction. His idea was to melt the unremarkable chain down for scrap.

At this point (Bannerman says) Abbey stepped in and, recognizing their importance, saved the links from destruction by buying them all. After making a few big sales, Abbey sold the leftovers back to Bannerman.

The problem is that none of the chain links sold by Abbey or Bannerman were authentic. In reality, Abbey had acquired a British mooring chain, cast in Wales in the mid-nineteenth century. Made of smooth rolled iron (rather than the rough, hand-hammered metal of the authentic Chain), Abbey’s links were almost double the size and weight of the West Point links. Despite the obvious differences, Abbey and Bannerman crafted a fiction from just enough fact that people believed it.

In reality, some of the original Chain was saved from destruction and left behind at West Point. Some of what was saved was exhibited at the 1864 Sanitary Fair. An auction at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1887 is also documented (although no mention is made of any chain).

Although some questioned why their links differed from the originals, most either remained silent from embarrassment or made excuses (the Buffalo Historical Society wrote in 1921 that their Bannerman links are larger because they were made for a point in the Chain where the strain from the River was greatest).

By the time all was said and done, spurious chain links were scattered from Vermont to California, from small-town museums to the Smithsonian archives. The whole fraud wasn’t pieced together until 1990 when Hudson River historian Lincoln Diamant investigated all the known links for his book Chaining the Hudson: The Fight for the River in the American Revolution, a wonderful history of the West Point Chain.

A few authentic links still survive, most notably at Trophy Point in the United States Military Academy at West Point. Thirteen links ring a monument to the ingenuity, dedication, and patriotism of those who created it. Most of the chain was reused during the 19th century by the West Point Foundry.

You can even see pieces of the fake chain links that Abbey sold. A stretch of 25 links runs across the grounds of Ringwood Manor, the former New Jersey summer estate of Peter Cooper and Abram S. Hewitt. Hewitt purchased the chain segment from Abbey in the early 1900s, but almost immediately realized he had been conned. He had the links analyzed and found out they were made of English iron. The chain remained on the grounds as a reminder of the local area’s iron mining history.

Next, check out Famous Landmark Sale Scams from New York to London

Get in touch with the author at Bookworm History

Editor’s Note: This article, originally published in May 2016, has been updated in February 2024.

Subscribe to our newsletter