A Salvaged Banksy Mural is Now on View in NYC

This unique Banksy mural goes up for auction on May 21st in NYC!

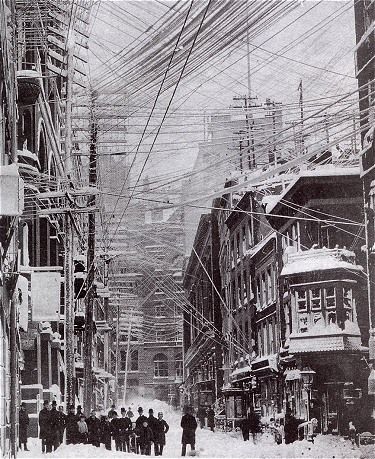

Image via Wikimedia Commons

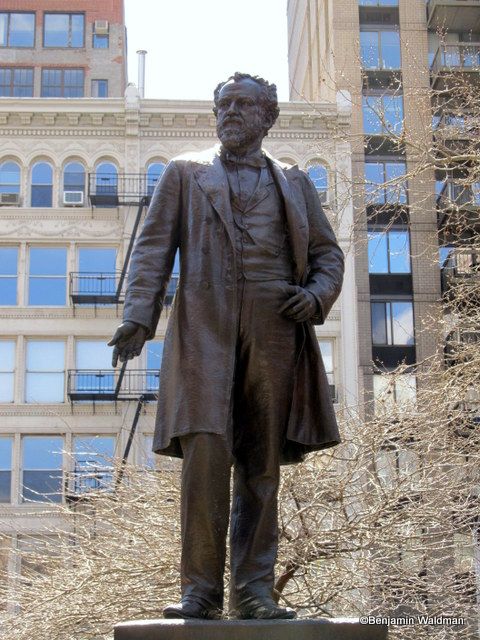

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Towards the end of a warm March day, in 1888, snow started drifting, quite expectantly, into New York City. Within a two day period, 21 inches of snow fell over the City, making it the third largest accumulation on record. This record breaking storm caused 30 foot high snow drifts and wind gusts of up to 75 miles per hour that paralyzed the city. The highest reported drift was 52 feet, in Gravesend, and reports stated that three story houses were hidden beneath the snow.

The Central Park Observatory reported the record for coldest temperature in March was set during the storm at 6 degrees. Referred to as the Great White Hurricane, the storm disabled the City’s transportation and communications systems. Roads and highways were blocked, train service (both at grade and elevated were suspended), ships were stuck in the harbor, horse-drawn streetcars and taxis halted operations, and telephone, telegraph, and electricity was non-existent. Some electricity was even shut off preemptively, an unheard of precaution at the time, and the rest was lost due to the collapse of telephone poles, often in a domino effect. The New York Stock Exchange closed for two days. The New York Times opined that, “[i]t is hard to believe in this last quarter of the nineteenth century that for even one day New-York could be so completely isolated from the rest of the world as if Manhattan Island was in the middle of the South Sea.” The frigid weather and the plethora of snow caused the deaths of over 200 people in New York City, including a famous politician.

On Monday March 12, 1888, Roscose Conkling, a former United States Senator and Representative from New York (and the the last person to refuse a United States Supreme Court appointment after it had been confirmed by the Senate) left his office and headed home. Due to the weather, Conkling hailed a cab to reach his destination at the Hoffman House on Madison Square and Twenty-Fifth Street. To Conkling’s chagrin, the cabbie demanded fifty dollars. Rather than pay the exorbitant fare, Conkling decided to walk the two and one half miles back to his home. When he reached Union Square, he took an ill advised short cut through the Park. There, he fell into a snowbank and was buried up to his armpits.

After twenty minutes, Conkling managed to free himself and make it to the front door of the New York Club, mere feet from his intended destination, where he collapsed. One month later, he died becoming the storm’s most famous victim. Five years later, Conkling’s friends petitioned the Mayor and Parks Board to erect a sculpture of him in Union Square Park. Their request was denied because the officials did not believe that Conkling belonged alongside the likes of Washington, Lincoln, and Lafayette. However, they did allow a statue of him to be erected in Madison Square Park.

The 1893 statue of Conkling in Madison Square Park

October 2012 will forever be remembered as the year the mass transit stopped working and Halloween was cancelled (at least in New Jersey) because of Hurricane Sandy. This hurricane nor’easter caused damage to the City’s ability to operate on a scale not seen since the 1888 storm. Bus, subway, and train service was suspended. Electricity was once again partially shut off preemptively (this time only to portions of lower Manhattan). All major bridges and tunnels connecting Manhattan to Long Island (including Brooklyn and Queens) and the main land were closed, with the exception of the Lincoln Tunnel. Manhattan again felt as if it were “in the middle of the South Sea.” Additionally, Sandy caused the first two day weather related closure of the New York Stock Exchange since the 1888 storm.

While the economic toll from Hurricane Sandy is likely greater than in 1888, the human toll is much smaller (though no less tragic). Additionally most of Northern Manhattan retained its power which can be traced to the aftermath of the Great White Hurricane. In the 1880s, a “forest of poles” and wires clouded the skies above New York City. Wires snapped on a regular basis spraying sparks and occasionally injuring (or killing) an unlucky passerby. By the mid-1880s, the City attempted to have the wires buried. However, the businessmen who owned the wires, including Jay Gould of Western Union, fought the City in court and won.

After the storm, The New York Tribune printed an editorial reminding New Yorkers that not only had a law had been passed to bury the wires, but that the companies, which owned them, had more than enough money to make it happen. The editorial stated that it was “high time to have done with tricks and subterfuges to avoid the plain requirements of duty and of common sense.” While the storm helped garner even more public support to bury the wires and dramatized the myriad of problems with them, the businessmen would have none of it. Brush Electric Company even threatened to leave New York if the City persevered.

In January 1889, Hugh Grant defeated Abraham Hewitt and become Mayor of New York City. This change in administration coupled with two very public deaths from the downed wires finally resulted in an end to the injunctions for the companies that owned the wires. Within the next few years, all of the poles and wires were dismantled and the wires were buried underground where they would be more secure. This ensured that neither wind nor snow would cut off electricity to New York City again.

Just as the Blizzard of 1888 dramatized the limits of the City’s technology at the time and the need to adapt, Hurricane Sandy has had the same effect. Governor Cuomo has spoke about the possibilities of adding levees into Lower Manhattan, other have proposed a surge barrier, and ConEdison will now have to reevaluate how to make it submerged wires even more secure. Change in New York City is often slow to occur, but once it does, it helps the City maintain its edge and prominence well into the future.

Subscribe to our newsletter