Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

For students and American expats in Paris, there is a nearly cult-like worship of Hemingway’s old haunts. Even for Parisians, Hemingway is a figure that seems to belong in Paris, like his namesake bar at The Ritz. Though his fiction is largely set elsewhere, in Spain, Africa, or the United States, Hemingway left a testament to his love for the City of Light: A Moveable Feast.

For better or worse, many of the Paris institutions mentioned in the book still remain. Perhaps the only curse of Hemingway’s legacy is that so many of his haunts have become tourist destinations, and have lost their air of authenticity. But, after following the routes set out on this map, you can be the judge of that for yourself.

View

France & Hemingwayin a larger map

We start at Place Contrescarpe, where Hemingway opens the book with the cold wind that would strip the leaves off the trees and patrons huddled in the Café des Amateurs would stay drunk all the time. From there, Hemingway would walk up Rue Moufftard, “that wonderful narrow crowded market street” towards Rue Cardinal Lemoine, where he rented a room on the top floor of the hotel where Verlain died.

After working for a while in that cold room, he’d walk down past the Lycée Henri IV and the church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont and Place du Pantheon, til he cut into Boulevard Saint-Michel and continued past the Cluny and Boulevard Saint-Germain until he arrived at a good café on Place Saint-Michel, where he ate oysters with white wine and wrote short stories.

Rue Moufftard, in the 5th arrondissement

Rue Moufftard, in the 5th arrondissement

Hemingway and his wife often called on Gertrude Stein at her studio apartment at 27 Rue de Fleurus. He describes it as “one of the best rooms in the finest museums except there was a big fireplace and it was warm and comfortable and they gave you good things to eat and tea and natural distilled liquors made from purple plums, yellow plums or wild raspberries.”

Gertrude Stein apparently loved giving out advice and preferred talking about writers’ personal lives instead of their work. She instructed Hemingway to forgo buying clothes and buy paintings instead, like the Picassos and the Matisses she had in her apartment. She was the first one to call Hemingway and his contemporaries “The Lost Generation.” Hemingway and his wife soon moved to 113 Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, on the southern tip of the Jardin du Luxembourg, a brief walk from Stein’s apartment.

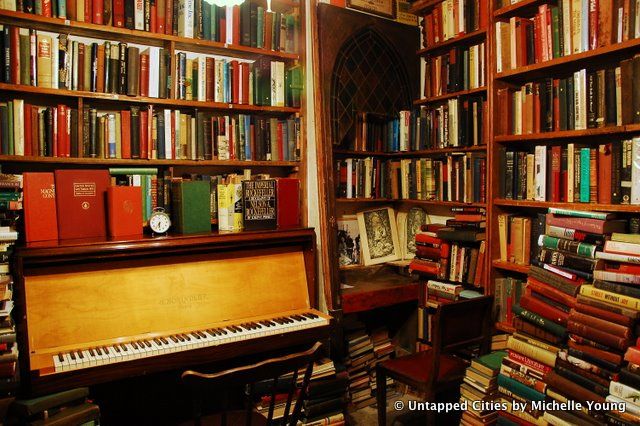

Hemingway often visited Shakespeare & Co., Sylvia Beach’s bookstore and lending library, which was originally located at 12 Rue de l’Odéon. When Hemingway was young and broke, Beach gave him a card for her lending library and told him to pay at his convenience. Now the iconic English-language bookstore is located on the quay across from Notre Dame.

Hemingway reports asking Beach when Joyce usually came in and telling her that he had seen Joyce and and his family eating at Michaud’s. It was an expensive restaurant, but Hemingway and his wife treated themselves to dinner there after winning some money at the races. He often bet on the horse races at Auteuil or Enghien.

When Hemingway hadn’t gone to the races in a while and was low on cash, he’d often alter his route, walking from Place de l’Observatoire to Rue de Vaugirard, so he wouldn’t be tempted by the bakeries. He writes about hunger as “good discipline” and tells the reader, “There you could always go into the Luxembourg Museum and all the paintings were sharper and clearer and more beautiful if you were belly-empty, hollow-hungry. I learned to understand Cézanne much better and to see truly how he made landscapes when I was hungry.” When the hunger pangs finally became too bothersome, he’d stroll over to Brasserie Lipp, where he’d enjoy a cold liter of beer (yes, a liter!) with pommes à l’huile and sausage.

Other times, he’d go to the Closerie des Lilas, which he preferred over Le Dôme or La Rotonde, because it was less ostentatious. Even before Hemingway’s time, poets used to frequent the Lilas, which might be why he liked it so much. For a glimpse into 1920s Paris, Hemingway tells us, “In those days many people went to the cafés at the corner of the Boulevard Montparnasse and the Boulevard Raspail to be seen publicly and in a way such places anticipated the columnists as the daily substitutes for immortality.”

When Hemingway went to those places, he often ran into someone important like Ford Madox Ford or Ezra Pound, who was trying to get everyone to give some money to T.S. Eliot so he could quit his job at a bank and devote himself to writing.

One day, Hemingway met F. Scott Fitzgerald at the Dingo Bar in Rue Delambre. Fitzgerald lived at 14 Rue de Tilsitt, near L’Étoile and often went to the Ritz Bar. Shortly after they met, Fitzgerald asked Hemingway to accompany him to Lyon to retrieve his car, which he and Zelda had to abandon because of bad weather.

Hemingway goes on to describe a rather bizarre trip. Fitzgerald had instructed Hemingway to take the train to Lyon, but missed it, so Hemingway didn’t know if he was coming at all. They managed to find each other at the hotel. The journey became stranger as Fitzgerald revealed himself to be increasingly neurotic, obsessive and hypochondriac, as a reaction to Zelda’s controlling nature. Later, the bar chief at the Ritz asked Hemingway who was that Monsieur Fitzgerald that everyone was always asking him about? Hemingway promised to write something about him in a book about the early days in Paris. Today the main bar in the Ritz is still referred to as the Hemingway Bar.

Get in touch with the author @lauraitzkowitz.

Subscribe to our newsletter