After-Hours Tour of the Fraunces Tavern Museum: "Path to Liberty"

Explore a new exhibit inside the oldest building in Manhattan, a witness to history throughout the Revolutionary War Era!

Even before Grand Central Terminal officially opened on February 2, 1913 New Yorkers were teased with descriptions of the mural that had been painted on its vaulted ceiling, with the New York Times telling of its “effect of illimitable space” and how “fortunately there are no chairs in the concourse or…some passengers might miss their trains while contemplating this starry picture.” While the effect the painting has on commuters today is the same, the mural on the Grand Central ceiling has undergone significant change. In fact, it’s not even the same mural.

For more secrets of Grand Central Terminal, join us for an upcoming tour:

Tour of the Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

The Grand Central ceiling took dozens of people to create but was primarily the work of five men: architect Whitney Warren, of Warren & Wetmore, the Terminal’s architects, French artist Paul Helleu, muralist J. Monroe Hewlett and painter Charles Basing of the Hewlett-Basing Studio in Brooklyn, as well as astronomer Dr. Harold Jacoby of Columbia University. Drawing heavily from Johann Bayer’s 1603 star atlas Uranometria for the design of the constellations, the mural was originally painted right onto Grand Central’s plaster vaulted ceiling.

Less than two months after the Terminal opened one astute commuter noticed the design of the ceiling is actually backwards; west is east and east is west. This was a bit embarrassing for the New York Central Railroad who, when the Terminal opened, had published a pamphlet about the ceiling writing “it is safe to say that many school children will go to the Grand Central Terminal to study this representation of the heavens.”

Both Jacoby and Basing were asked how the ceiling’s layout could have gotten flipped. Jacoby offered the explanation that the original diagram had been laid out correctly and would match perfectly against a celestial atlas. As such, the diagram was meant to be held overhead. When the image was projected onto the ceiling for painting, Basing (according to Jacoby) must have laid it on the floor and projected it upwards, reversing the image. As for Basing, he “showed little interest in the technical defects and added that he thought the work had been done very well.”

A postcard of the ceiling mural, probably based on the original diagram Jacoby mentioned, shows the layout as it was meant to be, with Cancer in the east and Aquarius in the west. But something about this layout is still troubling. Even though all the constellations are now where they should be, Orion is reversed! Although he’s placed in the correct location, the constellation itself is backwards! Which means that on the ceiling itself (which was projected backwards) he’s the only constellation whose stars are oriented correctly.

To figure out why Orion is flipped around is difficult to do and requires a bit of a logical leap. It could be that someone wanted Orion to be facing Taurus, the celestial hunter squaring off against the legendary bull. In order to do this, Bayer’s Orion would have to be turned around. Which is even more awkward, because he already was.

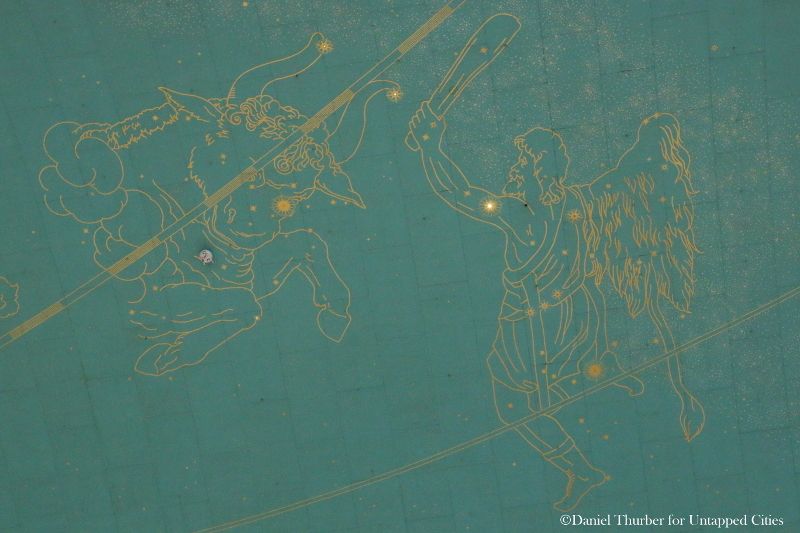

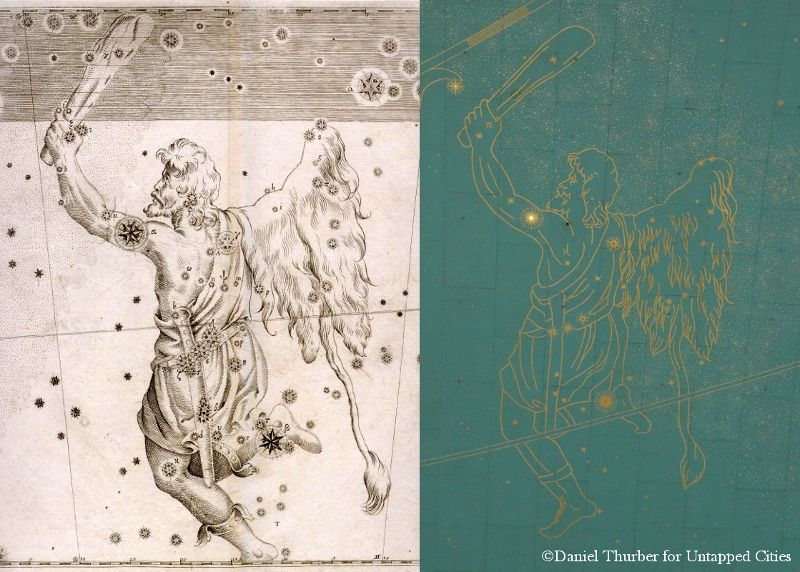

The images of the constellations were based almost line for line on the engravings in the Bayer Atlas and it is here, in the Uranometria, that the source of Orion’s Grand Central confusion lies. Typically, when constellations were depicted in celestial atlases they followed the Hipparchus rule; that is, if the stars are depicted as they would be seen from the earth, the constellation around them will be drawn facing the earth.

But Bayer departs from this rule. While he draws Orion’s stars as seen from the ground, he has Orion facing away. Bayer’s reversal becomes all the more fascinating when you consider Rigel, the star Bayer drew as Orion’s right ankle, is a word derived from Arabic meaning “left leg”. This wouldn’t have been all that confusing except that Bayer then had him looking towards his uplifted arm (depicted holding a club) instead of towards his more traditional lower arm (with the lion’s skin) which would have him staring straight at Taurus.

Bayer faced Orion the wrong way, then the mural turned him around, only to be spun again when the original diagram was projected backwards.

By 1924, just 11 years after it was painted, the mural was in sad shape. A leaky roof had “filled [the] sky with tramp comets and a mildewed way” while causing the original blue background to be “invaded by patches of white, black, and green.” Another twenty years later and the ceiling had “faded to a hue something like that of a khaki shirt overdosed with Navy blue” with “a vast brown streak near the center and most of the gold…flaked off the starbeams.”

In August of 1944 the scaffolds went up, both to repair the leaky roof and the moldy mural. In June, 1945 the mural was revealed to be “entirely restored.” Except that it wasn’t.

Rather than restore the original mural the New York Central simply painted a new one. Covering the entire ceiling with eight-foot by four-foot sheets of cement-and-asbestos board, an entirely new mural was painted from scratch. Looking up at the ceiling today, it’s easy to see the outlines of the boards.

Not only was a completely new mural painted, it was altered from the original design. While the backwards orientation was kept, the new constellations were repainted with much less detail than their original counterparts, bearing only the outlines of the intricate Bayer engravings upon which they were based.

Even more curious is the sudden appearance of an entirely new constellation. Take a good look at the picture below. It shows the ceiling as it was in 1914, shortly after the Terminal opened. Above Aries’ head is depicted the small constellation Triangulum, literally “The Triangle”.

Grand Central Terminal in 1914. Image courtesy of the New York Transit Museum

Now look at Aries today. Do you see it? The second triangle?

Not part of the original design, this second triangle was added during the 1945 restoration. Why it was will probably never be known. The constellation, known as Triangulum Minus (or “The Lesser Triangle”) did appear in a few celestial atlases in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but is not in Bayer and had long been obsolete by 1944.

Will the original mural ever be seen again? Probably not. While it is uncertain how much of the original is even left underneath the “restoration” panels, to remove them may be to invite other issues as they contain asbestos. In their present form, bolted securely to the ceiling, they pose no threat and it is unlikely Metro-North would risk removing them.

Join us for our upcoming tour:

Tour of the Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

Next, read about The Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal. Get in touch with the author at Bookworm History.

Subscribe to our newsletter