Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

As New York City grew and developed in its earliest years, several cemeteries became iconic public grounds. In many cases, the removal of burial sites that contained the bodies of African Americans erased the unpleasant and violent history of a city built on slave labor. In the past twenty years, at least three New York City sites were discovered to have been African burial grounds where slaves were exclusively buried.

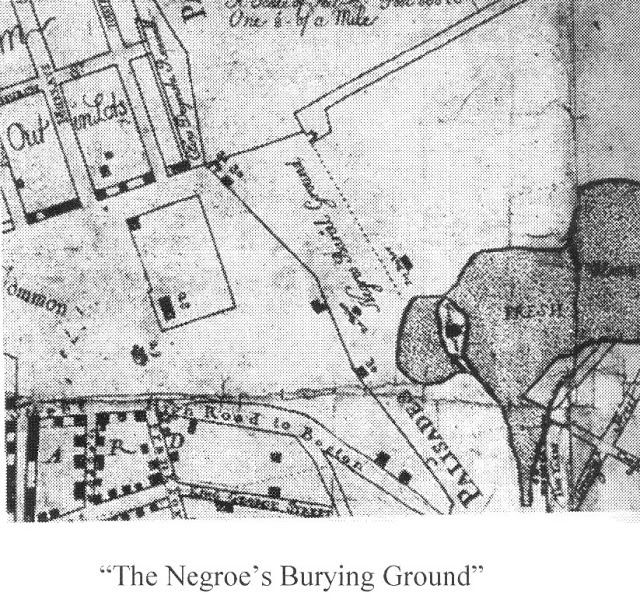

The first rediscovered burial ground for slaves was discovered in 1991 in Lower Manhattan amidst construction for a General Services Administration building. According to the New York Times, graves were discovered 24 feet below ground, and more bodies were soon discovered in the area. It was then determined that these bodies were interred in what was called “Negros Burial Ground” on a 1755 map. 419 bodies were discovered here in total and it is the largest colonial-era African slave cemetery in America.

From Stokes, Iconography of Manhattan Island, Vol. 1- 1763

That year, a fervent case was made for the establishment of a landmark here, and the site was declared a National Historic Landmark by 1993. The African Burial Ground National Monument was declared such in 2006 when George W. Bush signed a proclamation. The proceeding dedication in 2007 officially renamed Elk Street as “African Burial Ground Way.” In 2010, the African Burial Ground Visitor Center was built in the Ted Weiss Federal Building.

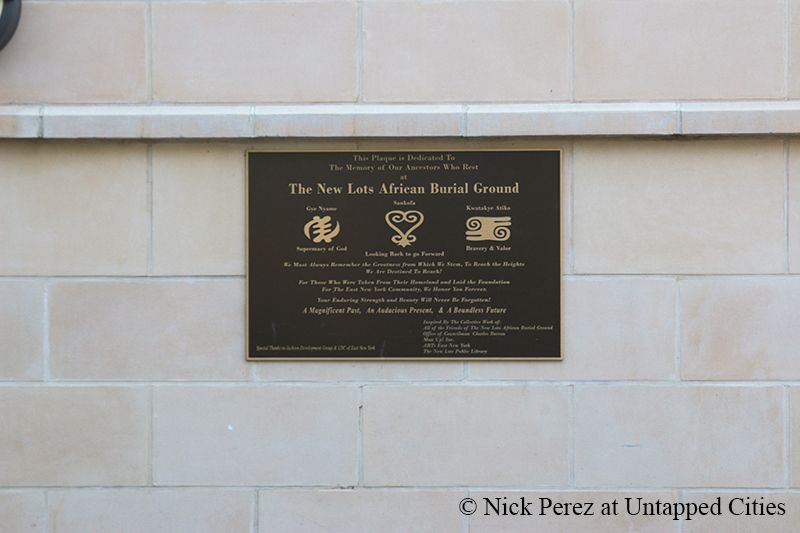

Another burial ground in East New York was officially recognized in 2013. The burial ground was discovered in 2010 on New Lots Avenue in Brooklyn and the area was renamed “African Burial Ground Square.” There is also a plaque with the engraving “Your enduring strength and beauty will never be forgotten.” It is located on Livonia Avenue between Barbey Street and Schenck Avenue.

Local officials discovered the existence of the burial ground when they were digging into historic documents. While studying old maps, they found one from 1878 that showed an African burial ground in East New York. Charles Barron, former council member for East New York, led the recovery project and renamed the area. They designated it as a historical landmark to raise more awareness about the lost lives and culture.

Anna Aguirre, Director of United Community Centers in East New York, says “Charles Barron put a plaque to remember the African Burial Ground in East New York, but they want to do something more visible to remember the people who lost their lives and its history.”

When the Department of Transportation began its environmental review process of the Willis Avenue Bridge in 2008, bodily remains were found under a part of the depot. Upon further investigation, the remains were connected to the Elmendor Reformed Church, the oldest church in Harlem. The Harlem African Burial Ground Task Force was assembled the following year to decide on ways to memorialize and maintain the space.

The 126th Street Bus Depot has since been defunded. In 2011, the MTA officially acknowledged the colonial cemetery. An archeological exploration into the area last year by the City of New York has opened the possibility for the task force to engage in discussion about converting the site into memorial and non-memorial uses. Below is a New York Senate Public Hearing on protecting Harlem’s African Burial Ground:

The Harlem African Burial Ground Task Force aims to obtain landmark status and to build a community center at the space. The Harlem African Burial Ground Task Force, other community stakeholders and New York City agencies are attempting to come up with community-based planning processes for the redevelopment of the space that will honor the history of the site and meet community needs.

Subscribe to our newsletter