Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

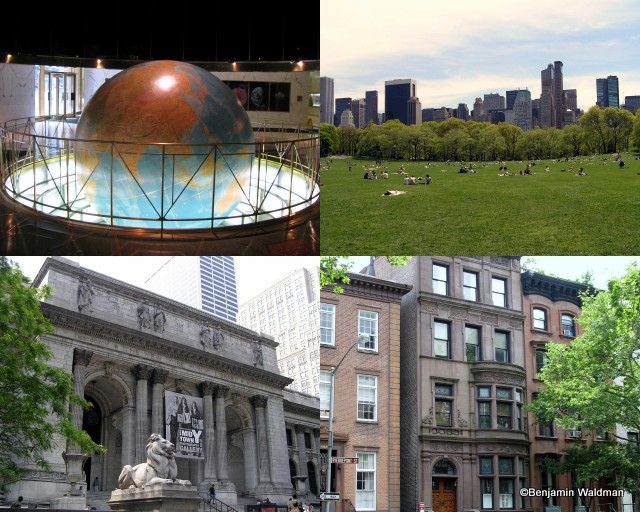

The different types of NYC landmarks: The Daily News Building (Interior Landmark), Central Park (Scenic Landmark), New York Public Library, Main Branch, (Individual Landmark), and Brooklyn Heights Streetscape (Historic District)

The different types of NYC landmarks: The Daily News Building (Interior Landmark), Central Park (Scenic Landmark), New York Public Library, Main Branch, (Individual Landmark), and Brooklyn Heights Streetscape (Historic District)

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission arose out of the fires that consumed McKim, Mead, and White’s Pennsylvania Station. Their work has ensured that New York City’s history will forever be a part of the City’s landscape. The Commission was established by Mayor Wagner in 1965 pursuant to the Landmark’s Law in order to:

(Source: NYC Landmarks Preservation)

The Commission is governed by Chapter 3, Section 25, of the New York City Administrative Code and has four types of designations at its disposal. The Commission can designate a property, object, or building an individual landmark, which protects the designee’s exterior; an interior space can be designated as an interior landmark, such spaces must be customarily accessible to the public; a landscape feature or group of features can be designed a scenic landmark, which must be situated on city-owned property; and lastly, the Commission can designate an area as a historic district, which must represent at least one period or style of architecture typical of one or more areas in the City’s history. As a result of this broad spectrum of designations, New York City landmarks form a diverse corpus.

From time to time, the Commission’s designations, or nonfeasance, have caused controversy and legal action. In their early years, the Commission was accused of not wielding a big enough stick. Ernest Flagg’s masterpiece, the Singer Building, was lost because the Commission did not want to take on US Steel, which then owned the building, and the former Metropolitan Opera House was lost when the Commission caved into pressure from the Metropolitan Opera. Recent controversy include the commission’s rejection of the proposed Clinton Hill Historic District.

Simultaneously, the Commission’s decision to designate a landmark has been as vociferously fought. One of the Commission’s earliest tests resulted from its decision to designate Grand Central Terminal an individual landmark. Pennsylvania Central Railroad, which owned the station at the time, wanted to build a large office tower above the station. In a landmark Supreme Court decision, the Court upheld the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission’s mandate to designate landmarks, and the protective status thereby attached. Modern controversies include the Octagon, on Roosevelt Island, the Mount Morris Bank (later Corn Exchange) Building, in Harlem, and the ruins of the Smallpox Hospital, on Roosevelt Island, which were allowed to fall into disrepair, and 2 Columbus Circle, whose facade the Commission allowed to be altered.

Today, groups including Landmark West! and the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation argue that the Commission needs to protect larger swaths of the City and do a better job protecting structures that have been landmarked. Simultaneously, groups including the Responsible Landmarks Coalition, and other real estate trade organizations seek to limit the Commission’s powers. Recently proposed bills before the City Council would mandate that the City Planning Commission review whether a historic district designation would conflict with any city plans for future development and repeal the current requirement that the Commission approve changes made to homes in historic districts.

Despite some of the above mentioned controversies, there is generally a wide consensus that, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission plays an extremely important and successful role in the City.

This is the first in a series of articles exploring landmarking in New York City.

Subscribe to our newsletter