Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Some people might say New York City has a hard time holding on to its past, and it’s not just classic architecture and cool dive bars that disappear without a trace. Fossils, too, are easily lost beneath the city streets. Thousands of years ago, prehistoric animals roamed the area, including the mighty mastodon (Mammut americanum), an ancient animal with an outsized presence and huge historical significance.

The first mastodon fossil ever discovered was unearthed in 1705 by a Dutch farmer in Claverack, New York, a small town about 100 miles north of Manhattan. Rumor has it that the farmer brought the fossil—a tooth about the size of a man’s fist—to town and promptly exchanged it for a glass of rum. The tooth then went up the political food chain, making its way to the governor of New York and finally the King of England.

What made this mastodon fossil so significant is that it came well over a hundred years before dinosaurs were officially discovered. At the time, some believed the tooth belonged to one of the giants mentioned in the book of Genesis because nobody knew what a mastodon was. The concept of fossils, extinction, or even an earth more than a few thousand years old was unfamiliar to say the least.

Mastadon tooth in the collection of the Staten Island Museum

A little more about that tooth. The word mastodon is Latin for nipple tooth, and it’s these uniquely shaped teeth of theirs that distinguish them from their cousins, the woolly mammoth and the modern elephant. Mastodons were also shorter than their cousins, standing about ten feet tall. They lived in North America, typically near the coast, up until about 10,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, at which point their species died off completely. This event, also known as “the fifth extinction,” saw the end of other North American megafauna, including giant ground sloths, saber tooth tigers, and Camelops, a relative of modern-day camels.

According to Carl Mehling of the American Museum of Natural History, there have been over a dozen mastodon fossils found in New York City. But, there’s a catch.

“Almost none of them exist anymore,” says Mehling. “They were found way before there was a proper repository like us. There’s just records of them being found, but no specimens.”

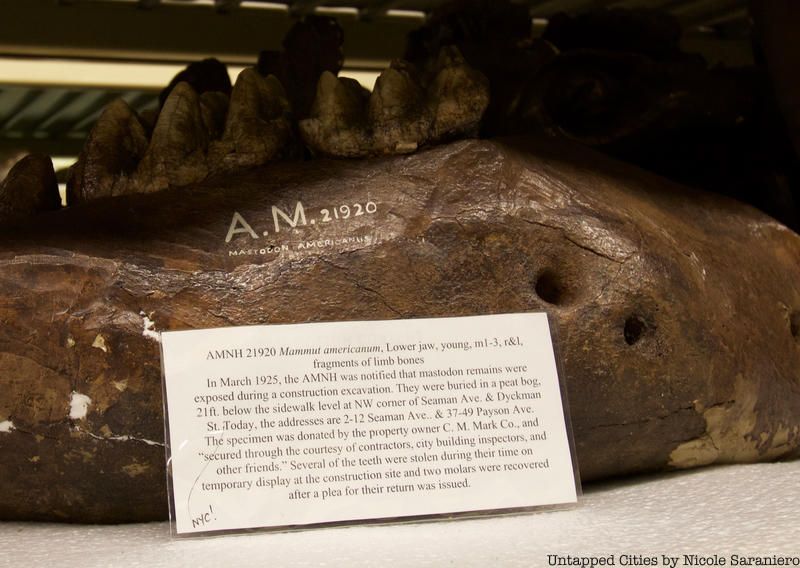

One of the more famous discoveries—one that eventually made its way to the museum—was found in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan in 1925. Up on Seamen Avenue (where it incredibly intersects with Cumming Street), a new apartment building was under construction. As the crew hollowed out the grounds for the foundation, their shovels struck bones, specifically the lower jaw and teeth of a young mastodon.

Later that day, Dr. CC Mook from the Museum of Natural History was dispatched uptown to collect the bones. Only, before he could arrive on the scene, Inwood locals made off with the majority of the specimen. One story, reported in The Sun on March 25, 1925, recounts a construction worker showing the fossils to a local milkman only to have the milkman run away with the bones. By the time Dr. Mook arrived on the scene, only three teeth were left. The story goes on to say that two of those remaining three teeth were promptly picked out of Dr. Mook’s pocket as he made his way from the construction site to his car.

By now, most if not all of those bones have been returned to the museum. Joining the Inwood specimen are other New York City mastodon fossils, including a piece of a tusk found during the digging of the Harlem River Canal.

Despite this relatively small amount of fossilized evidence, Mehling is quick to point out that many mastodons lived and died in New York City. The only problem is that finding a mastodon fossil—or any fossil for that matter—in New York City is, as Mehling puts it: “insanely hard.”

That’s because typically fossils are found in sedimentary rock, a mix of sand and mud or dirt. New York City’s foundation, on the hand, is mostly metamorphic rock, and therefore produces too much heat and pressure for anything to leave an imprint or a record.

“We have every indication that mastodons were all over the northeast. The fossils in New York aren’t some rogues who made it here. These animals were New Yorkers,” says Mehling. “There’s a damn good chance there were mammoths here and giant ground sloths and native horses, too,”

New York City, however, is simply not well equipped to preserve its past. What makes the Inwood mastodon so unique is that it died in the right place, where thousands of years later, New York City was given a rare glimpse into its ancient history. Carl Mehling chalks it up to “luck” that any fossils should exist here at all. Because, geologically speaking, New York City really is designed to carry on as though the past never existed.

Next, check out the new Titanosaur at the American Museum of Natural History

Author Tom Hynes writes a series for Untapped Cities about the history of NYC’s wildlife. Contact the author at @ThomasHynes.

Subscribe to our newsletter