How to See the Liberty Bell...in Queens

A copy of the famous American bell can be found inside a bank, which itself is modeled after Independence Hall!

The prosperity and opulence of New York in the 1920’s spilled from the speakeasies and jazz parties to the drawing board, as a number of the era’s ambitious architects unveiled dream structures of a future age. The city was rapidly expanding, but faced traffic and population congestion. At the turn of the 20th century, New York City had been linked to the outer boroughs and New Jersey via almost a dozen bridges, including the Manhattan, Williamsburg and Queensboro Bridges. With the rise of these soaring structures came a slew of ambitious proposals for even larger bridges, like Gustave Lindenthal’s Hudson River behemoth. Architect Raymond Hood–who would later help design Rockefeller Center–had a plan to trump them all, with skyscraper bridges of the future that would ease congestion and provide stunning waterfront views.

In a 1925 proposal in the New York Times Magazine, Hood envisioned a bridge stretching 10,000 feet across the Hudson, supported by multiple 60-story apartment buildings. Eventually the city’s bridges would hold dozens of these structures, accommodating up to 50,000 people. Hood told the Times the proposal was a “simple” and “easily practicable plan.” The Times went on to brainstorm a “great water-spanning town” with its own churches, schools, shops, garages and theaters. Residents could even descend to the river in elevators for a daily swim.

A 1930 sketch of Hood’s proposed Manhattan, with apartments on bridges radiating from the island. Courtesy of Bill Leuthold, University of Florida.

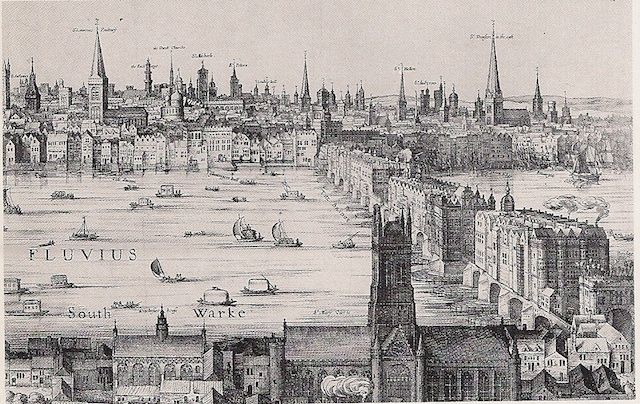

“Land has often been reclaimed from water for purposes of habitation and agriculture. What is so extraordinary about creating land over water?” the Times asked. Indeed, while new to America, Hood’s homes-on-bridges plan had been in use for centuries. It could be seen in Florence’s Ponte Vecchio, which has shops and homes built into it. Similarly, people in Tudor London built their houses and shops right on top of London Bridge.

A sketch of London Bridge in 1616. Source: London History.

Hood’s proposed 10,000-foot-long structure (20,000 feet of building property, taking into account two sides of the road) that was 50 feet deep would have an immediate value of $60 million, not including the apartment buildings. The mammoth cost was an immediate barrier to realizing Hood’s proposal. The Times acknowledged the economic costs of Hood’s plan, but did not refrain from endorsing his ambitious dream:

“With a dozen such bridges at intervals upholding their vast gleaming facades of differing design, with gayly dressed people upon their balconies and terraces, flags flying from their spires and boats weaving below them in the stream, the river would seem a Titan pageant, picked bodily out of the dream world.”

Fellow architect Hugh Ferriss’ 1929 rendering of Hood’s vision.

A year after unveiling his plans to the Times, in 1926, Hood’s vision became even grander as he told Liberty his dreams of building up to one hundred bridges 20,000 feet long, as wide as Park Avenue. In 1930, Hood presented a more detailed plan, called “Manhattan 1950,” at the Architectural League of New York’s annual exhibition. Manhattan in 1950 looked nothing like Hood’s vision, but a decade later, his optimistic outlook propelled him to design Rockefeller Center, a skyscraper city on land much like the bridge cities.

Subscribe to our newsletter