An Original Stone Eagle Comes Home to Penn Station in NYC

A 7,500-pound eagle sculpture from the top of the original 1910 Penn Station building has been returned after years in hiding!

Today there is hardly any trace of a community that inhabited the more than 100 structures that once existed along the A train tracks north of Broad Channel and east of the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center. The area had the unusual name of “The Raunt,” one of the few places in New York City, including “The Bronx,” that incorporates an article in its name. The Raunt Channel, which surrounded the community on three sides, may have itself been inspired by the Dutch word for “duck breeding place.

As the Raunt developed, squatters felt encouraged to settle there because the Town of Jamaica had jurisdiction over the area, but did not exercise title or collect taxes. By the late 1870s, the Town of Jamaica government noted the presence of buildings it had not permitted. On piles connected by boardwalks, residents had built small houses where they often crabbed from their windows. Other than three small hotels — Sehey’s East Side Hotel, O’Sullivan’s beside the trestle, and Paschke’s or Pasky’s — the area boasted fishing stations and boat-fishing clubs. Fisherman, crabbers, and summer vacationers even built a few summer residences along the railroad’s 4.8-mile-long wooden trestle.

Transportation to the area vastly improved when the New York, Woodhaven and Rockaway Railroad opened their line across Jamaica Bay in 1880. When The Raunt became a stop in 1888, the railroad rented space along their 150-foot wide right-of-way next to their stations for hotels and fishing stations. Four fishing villages were established in Jamaica Bay between the Rockaways and Howard Beach: Beach Channel, Broad Channel, The Raunt, and Goose Creek. Most of these villages had a wooden pedestrian bridge between their two platforms.

The railroad trestle monopolized traffic across Jamaica Bay, with the exception of steamboats from New York to the Rockaway Peninsula in the late nineteenth century. In the summer of 1884, as many as 87 trains crossed Jamaica Bay daily. However, during the winter months, the number of daily trains dropped to one or two. In 1887, the rail line was sold to the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) and eventually became the Rockaway Beach Division. In the early 20th century, Patrick Flynn began building a roadway across the bay, which was to include a trolley line and bicycle path. Opposition by the railroad and others and legal complications doomed the project. However, this did not stop the growth of The Raunt.

With added transport, came an increasing population in this fisherman’s paradise, the center of the shellfishing industry, and a joy to boatmen and yachtsmen. By 1897, there were six structures at The Raunt. By the turn of the 20th century, the area could house 250 summer residents. The area continued to gain popularity, leading to more than a hundred leases to be issued by 1913. Yet only fifteen leases remained as of 1953 as a result of various governmental and transit reasons. Most water (as well as coal, wood, and ice) arrived by boat or train. Pipes were later installed on the trestle. Some houses had flat roofs that drained into barrels.

The Town of Jamaica, followed by Canarsie and East New York began to discharge raw sewage into the bay in 1899. This ruined the shellfishing industry and made fishing a health hazard. Throughout the next decades, The Raunt declined drastically. Boating parties from the city ceased patronizing the boating stations at places like Goose Creek and The Raunt. At the beginning of the 20th century, railroad traffic to the fishing stations on the trestle began to decline. Prohibition shut down waterside bars and hotel saloons. The completion of the Cross Bay Boulevard Causeway (utilizing some of Patrick Flynn’s earlier roadway) in 1925 provided automobile access to Broad Channel and the other islands, but spelled doom for the waterside rail stops. Still, a long wooden footbridge was built to connect the road to The Raunt. A fire caused the further decline of The Raunt in 1931.

In the early 20th century, a plan surfaced to create the world’s largest deep-water port in Jamaica Bay with massive artificial islands containing three deep basins, later shown on a map from an October 22, 1930, New York Times article. After the plan faltered when regional planning supported new port facilities in New Jersey, business interests unsuccessfully lobbied to hold the 1939 World’s Fair there.

Through the efforts of Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, Jamaica Bay became a park in 1938, ending all plans to create a large industrial port and a new landfill. At more than 19,000 acres, Jamaica Bay Park is New York City’s largest park. Just over a decade after the bay became a park, Moses ordered The Raunt to be demolished. It became part of the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, the United States Department of Interior’s only wildlife refuge administered by the National Park Service. The Refuge contains an open bay, salt marsh, mudflats, upland field and woods, and small freshwater ponds.

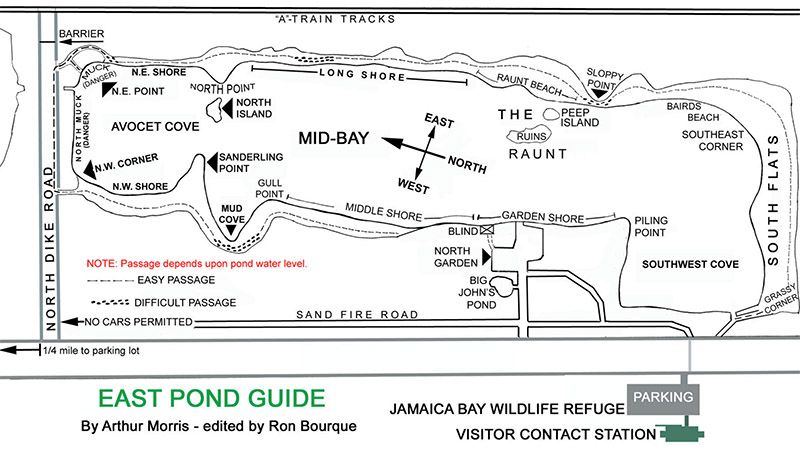

Yet, remnants of The Raunt lived on in the tons of rubble from the Pennsylvania Railroad tunnel excavation in Manhattan that were dumped at Goose Creek, The Raunt, and Broad Channel in 1906 to reduce the cost of trestle maintenance and eliminate fuel for fires. Years later, the NYCTA wanted to dredge the bay for material to build an embankment to replace the fire-prone and costly trestle. Moses would not permit the dredging unless dikes were constructed to impound fresh water to create two ponds for wildlife. With the creation of these ponds — the 117-acre East Pond and 45-acre West Pond — The Raunt ceased to exist.

The next time you ride the A train from the Howard Beach-JFK Airport Station to the Broad Channel Station, look out the right windows and imagine a small site where more than one hundred structures once lined its right of way. Today, they merely exist in memory.

Next, check out the 12 largest parks in NYC’s five boroughs! Get in touch with the author at PTannen9@gmail.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter