Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

It’s a cold November evening, and I’ve just valiantly fought my way through the sardine-packed Line 2 metro car and emerge, victorious, from the bowels of the Anvers station onto the pavement of boulevard de Rochechouart in the 18th arrondissement. I stand there for a bit, trying to remember if I should turn left or right (directions have never been my strongest suit). But Le Trianon Concert isn’t very hard to spot from where I stand. It’s my first time here, and I am struck by its beautiful facade. It stands illuminated and regal, almost out of place in the gritty neighborhood.

Montmartre is a place packed with tourists, but there aren’t a lot of cultural offerings. Maybe that will all change with Le Trianon Concert, which reopened to the jubilant public in early 2011. It has gone through many lives since it first opened in 1895, built on the garden of l’Elysee-Montmartre as a music hall. The place was patronized by artists, dancers and singers like Mistinguett, La Goulue and dancer/contortionist Valentin le Désossé. Its architecture was special as well: architect Edouard Jean Niermans reused the metal from the Gustav Eiffel’s Pavillion of France from the Universal Exposition of 1889.

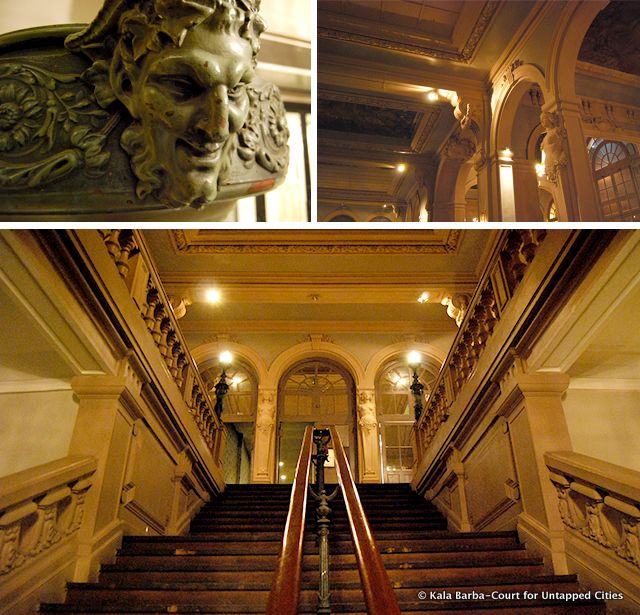

In 1900, at the height of the Belle Epoque, a fire ravaged the building to the ground. The owner, Albert Chauvin, lost no time in rebuilding. Architect Joseph Cassien-Bernard, student of Charles Garnier and designer of Pont Alexandre III, took charge of the reconstruction. The facade was inspired by Versailles‘ Grand Trianon, and it reopened two years later as “Trianon-Theater,” an elegant, 1,000-seater Italian-style theater, with two balconies leading to the sumptuous main theatre.

In the following years, Le Trianon adapted itself to the changes of time: it welcomed classic plays, opera, and cabaret. It was frequented by Picasso and Toulouse Lautrec, the latter known to have painted the regulars of Trianon. In 1938 it became “Cinephone Rochechouart“, a movie theater with plush 2-storey balconies, a place where Jacques Brel was said to have composed some of his songs in the 1950s. But for all its glory, the clientele slowly dwindled, and the Trianon closed its cinema in 1992.

***

I am surprised to learn that Le Trianon Concert was bought – or should I use the term ‘saved’? – by the 33-year old Julien Labrousse. Labrousse, at his young age, is no novice to this sort of thing: at the age 27 he was able to convince banks to invest 1,5 million euros into his project of renovating 19th century l’Hotel du Nord in the 10th arrondissement and transforming it into a restaurant and bar. He and his associate Abel Nahmias, a film producer and son of chef Dominique Versini of Casa Olympe, invested a mind-blowing 7 million euros in the project, without any help from the city. It reopened to the public in early 2011 to jubilant reviews. In a French interview last year, Labrousse mentions falling in love with Le Trianon, “this old abandoned castle in Paris”, when he visited it. For someone who loved reconstructing historical places, this project was ideal, a dream come true.

***

The concert ends (amazing set, Beach House!), and I wander over to the ballroom, where a bar sits on one end and a huge mirror hangs on the other. It’s calmer now, with most of the concert-goers heading to the downstairs bar and restaurant cheekily named Le Petit Trianon, to have another beer or a late dinner. At the entrance, the guard who checked my bag had told me not to use my camera; I spot him in a corner, and go over to ask him if I can now take some photos.

“Okay, but no photos of the concert hall,” he tells me. It’s dark, and my camera’s battery is dying. But even in the dimness, it’s easy to see that the 8 months of renovation has paid off. The original Belle Epoque staples have been retained, and the spaces that make up the building are a sight to behold : the theater, the ballroom, the winter garden (with its art nouveau floors and Eiffel staircase, renovated by Michael Gondry’s production designer Pierre Pell) and the art deco restaurant. I must definitely come back in the daytime.

At this point my camera dies, and so I lean against the balustrade and imagine the old and the new together. I see Toulouse Lautrec bobbing his head to a Deftones concert in the theater, or hipsters watching Louise “La Goulue” Weber perform a Can Can onstage. Clearly, reviving Le Trianon Concert was a smart move – these walls have seen too many great times to simply disappear. I say the show must go on.

Subscribe to our newsletter