✨You Can Touch the Times Square New Year's Eve Ball!

Find out how you can take home a piece of the old New Year's Eve ball!

Grand Central Terminal still stands as one of New York City’s most beloved landmarks, but its history is also a glorious story of creation, decline, and rebirth — much like the story of New York City itself. Grand Central Terminal opened on February 2nd, 1913 atop a previous version, Grand Central Station (built by Cornelius Vanderbilt for his New York Central Railroad). The station replaced an even earlier building, Grand Central Depot, which opened in 1871.

From the very beginning, Grand Central Terminal was intended to benefit both public and private interests — an arrangement that continues to this day. An extensive rehabilitation project in the 1990s restored Grand Central Terminal to its original glory, while the addition of retail and restaurants have made it a popular destination for both tourist and residents alike.

Despite its renown, Grand Central Terminal still holds many secrets and fun facts you may not know. Make sure to join us on our next tour of the secrets of Grand Central, where we’ll delve deeper.

Nestled between the Main Concourse and Vanderbilt Hall is an acoustical architectural anomaly in Grand Central Terminal: a whispering gallery. Here, sound is thrown clear across the 2,000-square-foot chamber, “telegraphing” across the surface of the vault and landing in faraway corners.

Although there are many whispering galleries you can find in New York City, few are as famous as the one in Grand Central Terminal. It was designed by the master tiling company, Guastavino but the real secret is that no one knows whether the whispering gallery was constructed with the intention of producing the acoustic effect that has made it so popular.

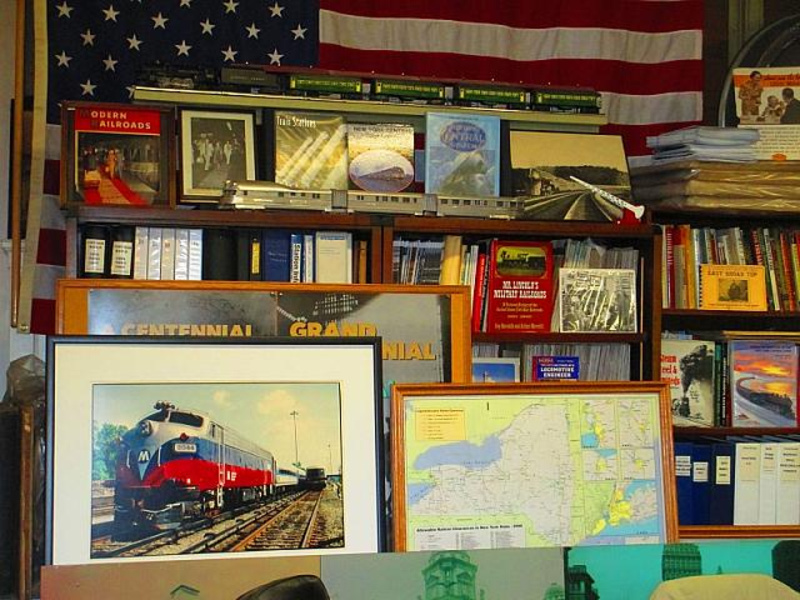

Tucked away on one of the upper levels of Grand Central Terminal is a small room bursting with railroad related books and ephemera. Officially known as the Williamson Library, the library was founded by former New York Central Railroad President Fred Williamson. In 1937, he gifted the space, in perpertuity, to the New York Railroad Enthusiasts, a group which he was a member of.

The Enthusiasts still use the library for meetings and events and it is rarely open to members of the public. In order to get in, you need special elevator access and access to the glass walkways. Once inside, the library is stuffed full of posters, paintings, photographs, over 3,000 books, and other artifacts related to rail travel. One of the most famous items in the collection is a piece of red carpet from the 20th Century Limited. Another fun library find, which we spotted in a photo on the NYRRE website, is a vintage Metro Man, a remote controlled robot introduced in 1983 to educate school children about railroad safety.

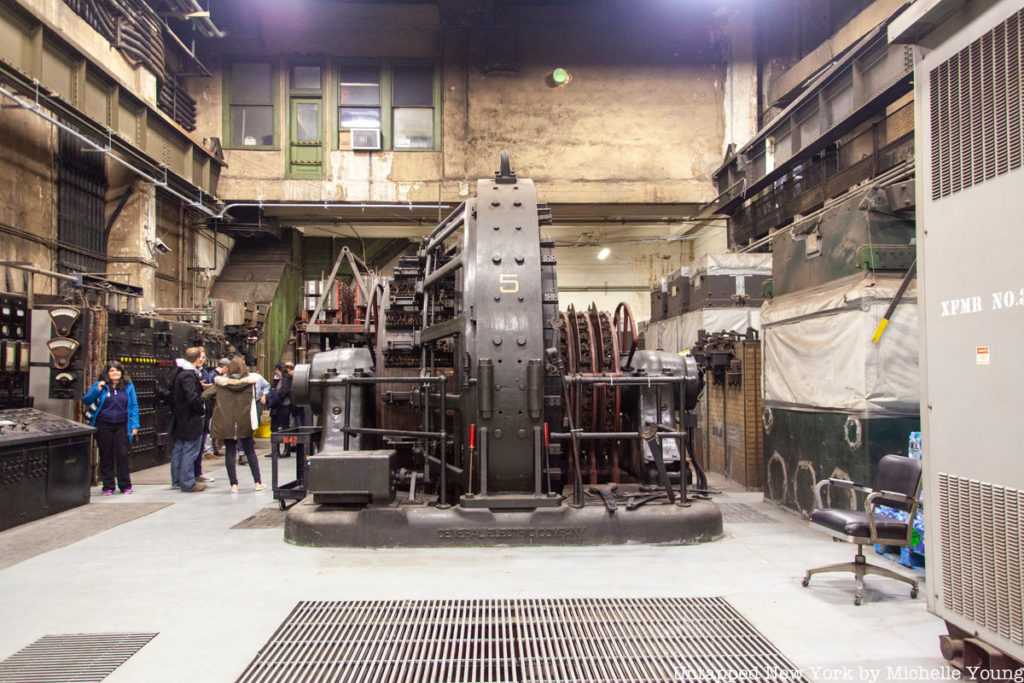

In a story long told by Daniel Brucker, the former docent-in-chief at Grand Central, a hidden room known as M42 does not appear on a single map or blueprint of Grand Central Terminal. Brucker said that this part of the basement played an important, clandestine role in World War II — it was so secret that you risked being shot on site if you went down there. It was allegedly the target of German spies during the war. In truth, while there were spies in America focused on destroying infrastructure, there is no contemporary evidence as of yet that Grand Central, or the M42 basement specifically, was a target.

M42 does exist however, and it houses converters that are responsible for providing all of the electricity that runs through Grand Central. Here, alternating current becomes direct current and provides power for the transportation of more than one million people each week up and down America’s East Coast. Check out our photos of this room deep below the terminal.

If you need to catch a train at the newly opened Grand Central Madison, you better give yourself some extra time. The brand new station is located 14 stories below ground and commuters need to travel down multiple escalators in order to get to the new platforms. The longest and steepest escalator in the MTA system brings travellers from the concourse level to the mezzanine level.

The giant escalator, which made quite an impression on visitors at opening day, is 182-feet long. Standing still, the ride up or down takes over a minute and half, which can feel like an eternity if you’re running to catch a train. Once you finally make it to the mezzanine level, you’ll see beautiful mosaic murals by artist Kiki Smith.

The Campbell Apartment in Grand Central Terminal serves as a testament to the grandiosity of another era. If appropriately attired, you can enter the room and sip on cocktails from the fin de siècle in this virtual museum to the opulence of New York’s high society of the past.

The apartment once belonged to John C. Campbell, a business tycoon; rumor has it that he used to sit behind his desk in his boxers, so that his trousers wouldn’t get wrinkled. The Campbell Apartment is also one of our favorite hidden bars in New York City.

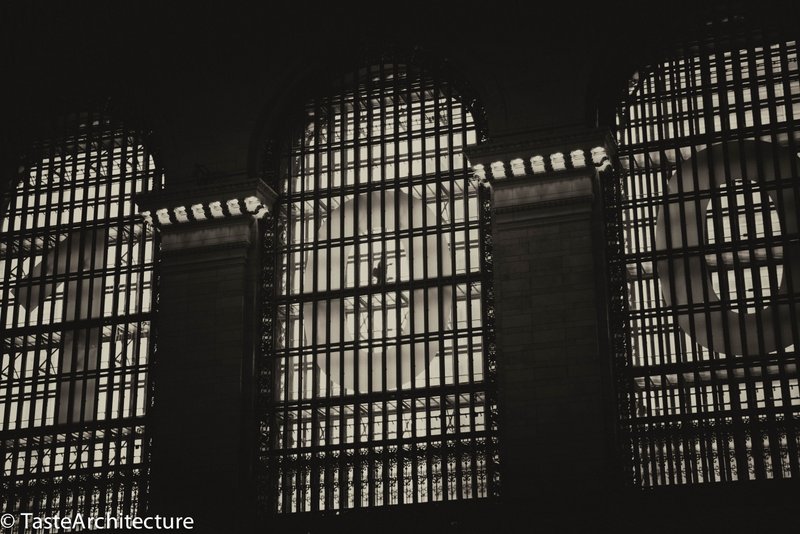

Inside the iconic arched windows of Grand Central Terminal’s main concourse, there are glass cinderblock walkways that go through the windows. If you look closely at the above photo, you’ll see someone crossing right between the first zero in 100. The walkways connect the offices above Grand Central so that employees don’t have to walk through the busy terminal.

The walkways are strictly off limits to the public and required special access for entry. Untapped New York had the chance to go inside once! You can read more about the walkways and check out our photos from inside here.

The sixth floor of Grand Central was once home to the Grand Central School of Art and the Grand Central Art Galleries. The galleries were established in 1922 by a collection of famous artists that included John Singer Sargent, Walter Leighton Clark, and Edmund Greacen. The school was founded a year later and boasted such notable pupils and teachers as Arshile Gorky, Daniel Chester French, Willem de Kooning, and Norman Rockwell. There were 900 students at its peak.

The galleries were designed by the prestigious firm Delano & Aldrich, who also designed the Knickerbocker Club, the Union Club, Oheka Castle on Long Island. At one point, the galleries stretched over 14,000 square feet, taking up 20 rooms. While the galleries lived on in different locations until 1994, the art school closed in 1944. The sixth floor gallery and art school space at Grand Central is now occupied b yailroad operations and offices.

One of the most fascinating things we shared in our article on The Roosevelt Hotel was a secret passageway below the hotel that once connected to Grand Central Terminal. While the hotel side of this tunnel has long been closed off, we recently discovered the forgotten side which emerged into Grand Central. Walking through the passageway through the Vanderbilt Concourse building (also known as the Manhattan Savings Bank Building) between 44th and 45th Street, there is a boarded-up section of hallway that would have led to the Roosevelt passage.

The hotel, opened in 1924, was part of the second phase of Terminal City’s construction between 1920 and 1931 and included such buildings as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the Graybar Building, 277 Park Avenue (where JFK would have his campaign office) and more. This investment underground, and the extension of it as Terminal City expanded, makes sense. Reed & Stem, accompanied by engineer William W. Wilgus, imagined a much more extensive Terminal City — covering dozens of city blocks up Park Avenue. World War II put an end to that grand vision.

The iron eagles perched at the corners of the edifice are vestiges from Grand Central Station, the L shaped predecessor of Grand Central Terminal. They are imposing and massive, with wingspans 13 feet wide. There were at least ten such eagles adorning the transportation hub before it was demolished to make way for the new one in 1902, and almost all of them disappeared after its destruction.

Nine have been located across the state of New York, many having been auctioned off to private estates and institutions. Some were found in backyards or as lawn ornaments; others at train stations on what was once a New York Central line. Another was found on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. Another is at a New Jersey petting zoo. Here’s a look at where all the eagles have gone.

Grand Central Terminal is one of the most romantic places in New York City, but when the station was first built, public displays of affection were relegated to a special room. In a New York Times article from 1913 that describes how the newly opened terminal building solved many problems of existing train stations, the writer notes that “indignant handlers of the baggage trucks would swear that their paths were forever being block by leisurely demonstrations of affection.”

The new “Kissing Galleries,” or “Romeo and Juliet” rooms as some people called them, provided a space away from the hustle and bustle where lovers could reunite, and get out of the way. These galleries, the paper notes, offered “exceptional vantage points for recognition, hailing, and the subsequent embrace.” One of these kissing rooms was located beneath the site of the former Biltmore Hotel in an area of Grand Central that came to be called the Biltmore Room. This room was blocked off due to construction on the East Side Access project but is now open to the public. Inside, you’ll find a remnant of Grand Central Terminal’s past.

There is one track at Grand Central that sits abandoned in the midst of the busiest train terminal in the world. That is Track 61, or the Waldorf Astoria track, originally built for freight and as a loading platform for a powerhouse that sat above it. This track is famously thought to have transported Franklin Delano Roosevelt, to hide the fact that he was wheelchair-bound due to polio.

After a long investigation, we revealed that although FDR did indeed use the track (at least one time was documented by Secret Service), but the long standing myth that the above train car was used by him to transport his Presidential limousine is definitively false. Read even more about this abandoned platform here.

The clock inside Grand Central is one of the city’s most famous meeting places (and it has its own myth!) But there is an even grander clock outside. The statue, “Transportation,” on the facade of Grand Central Terminal was designed by the French sculptor Jules-Felix Coutan, who refused to come to the United States to oversee the construction of his project. His reason: “I fear some of your [American] architecture would distress me.”

It took the builders seven years to construct Coutan’s massive sculpture of the Greek Gods. It is 48 feet high and weighs 1500 tons. Meanwhile, the clock below it is 14 feet in diameter and took twelve years to restore. If it’s true that the clock was made by Tiffany, it would be the largest in the world, but there’s reason to doubt that claim. While Grand Central Terminal’s official website calls it a Tiffany clock, the Tiffany Company has not confirmed (or denied it) and Tiffany experts say nay. When the clock was restored, no Tiffany signatures were found. Many sources that describe the clock in detail, such as the Terminal’s National Register of Historic Places designation and newspaper articles from the time of its opening, do not specifically call the clock a Tiffany piece. Further, books by Tiffany from 1913 through 2004 make no mention of the clock among the studio’s other work.

If you look up at the giant zodiac on the ceiling of the Main Concourse in Grand Central Terminal, you’ll find a small, dark patch of brick next to Cancer, the crab. This brick reveals what the station’s ceiling looked like before it was cleaned during the restoration project in 1998.

What made the brick so dirty? A very common myth says the grime is actually 70% nicotine and tar, thereby providing a great anti-smoking ad. However, according to the John Canning Company that restored the mural, “A detailed analysis of the dirt by scientists at McCrone Associates reported that the dirt and grime did not contain any nicotine or particles that could be attributed to cigar or cigarette smoke. The cause of the sometimes 2-inch thick grime was the decades of air pollutants – specifically car and truck exhaust, and the emissions soot and contaminants from industrial plants and apartment-building incinerators.” They say it was left in the restoration deliberately, as a reminder of the past.

A little known space called the Annex houses a tennis court that is accessible to the public (as long as you can get a reservation). Originally installed by a Hungarian immigrant Geza A. Gazdag in the 1960s, it was taken over by Donald Trump, who brought the likes of John McEnroe and the Williams sisters onto its clay courts. The space, at some point, had also been a ski slope.

The courts are now open to the public, although tracking them down takes a bit of investigative work (you’ll find that some GCT employees are even oblivious to the club’s existence). The easiest way to access the facility is to head to the Campbell Apartment, where you’ll find elevators in the lobby outside the bar that will bring you directly there. Alternatively, you can also take the elevators located halfway down the ramp that leads to the “Oyster Bar” and Tracks 100-117. Read more about the tennis courts here.

A remnant of the Biltmore Hotel can be seen on the western end of Grand Central Terminal. This tunnel once connected the grand Whitney Warren and Charles Wetmore designed hotel, part of “Terminal City,” to Grand Central Terminal. Access to the train terminal was an attraction for famous guests like F. Scott Fitzgerald and J.D. Salinger. Untapped New York’s Cheif Experience Officer Justin Rivers noticed the familiar herringbone tile pattern back in 2018 and discovered it is the work of master arch maker Rafael Guastavino.

The Biltmore Hotel closed in 1981 and redesigned as 335 Madison Avenue. Today, the Guatavino tiled tunnel is used as a parking garage. The entrance can be found on 44th street between Vanderbilt and Madison. If you visit the garage at night when no cars are parked in it, you will find various cab stop signs engraved on the ground, spread about eight feet apart from one another. Guests of the Biltmore arriving at Grand Central Terminal could have their luggage collected from the train by porters, travel via tunnel to an elevator in the hotel’s basement and be carried up into the hotel without ever having to step outside.

The painting of the constellations on the ceiling of the massive, cathedral-like Main Concourse is backward. No one knows for sure how the mix-up occurred, but the Vanderbilt family claimed that it was no accident; the zodiac was intended to be viewed from a divine perspective, rather than a human one, inside their temple to transportation.

Astronomer Dr. Harold Jacoby of Columbia offered a different explanation, saying that the original diagram had been laid out correctly and would match perfectly against a celestial atlas. As such, the diagram was meant to be held overhead. When the image was projected onto the ceiling for painting, painter Charles Basing of the Hewlett-Basing Studio (according to Jacoby) must have laid it on the floor and projected it upwards, reversing the image. Either way, you look at it, it’s still a beautiful mural.

Grand Central Theatre, opened in 1937 (possibly earlier), showing newsreels, shorts, and cartoons. The 242-seat theater operated for three decades and was then gutted for retail. It formerly was home to the Grande Harvest Wine shop, next to Track 17. Previous to that, the tenant was a photoshop. Renovations to the terminal in the 1990s revealed a ceiling that stylistically matches the one in the main terminal.

The first film to screen at the theater was the MGM film Servant of the People: The Story of the Constitution of the United States–one supposes Americans were a little more high-brow back then. According to the website, I Ride the Harlem Line, the theater was advertised as the “most intimate theatre in America” and was open every day until midnight.

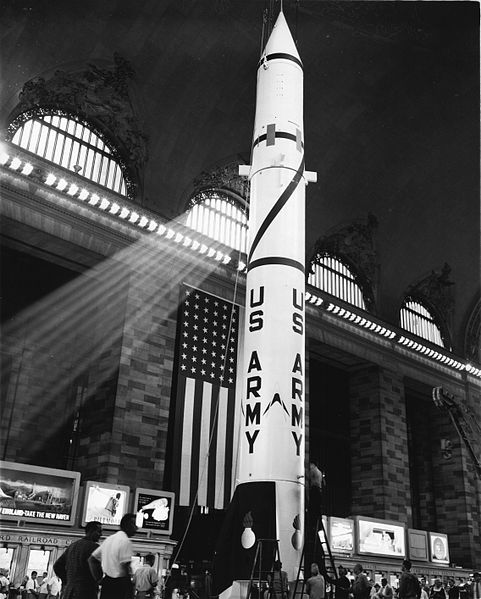

If you’ve ever heard that the 1957 Redstone rocket was so tall it bore a hole in the concourse ceiling, don’t believe it. There was a Redstone rocket, but it would have been too short to make a hole. The concourse is 125 feet high, and even sites that attempt to debunk the Redstone hole story get this fact wrong.

The sister of the Redstone rocket still exists so can be measured, which according to this story about where it now sits in Warren, New Hampshire, is 70 feet. This Wiki of astronautics has the original Redstone at 69.32 feet. In 1957 The New York Times reported that the Grand Central rocket was 63 feet and the height was in the headline for the article. Read more about it here.

As part of the renovation of Grand Central Terminal, red and green armchairs were placed in the dining concourse in 1998, modeled after the luxury wingchairs on the 20th-Century Limited Trains. The insignia on the chairs were the original logo of the terminal, in which Cornelius Vanderbilt placed a secret reference. As reported by The New York Times, the letters GCT in the symbol are formed such that when upside, the T becomes an anchor–an homage to Vanderbilt’s start in the ferry and shipping business.

There were 20 chairs and 4 loveseats in all, designed by David Rockwell and Sterling Surfaces, made of Corian with a custom colors to mimic a mohair texture. But in 2011, the chairs were removed, deemed too bulky for proper circulation of the space–and indeed they weighed 400 pounds each. On our Secrets of Grand Central Terminal tour, you’ll get to see these chairs up close and personal in a location high above the concourse. Full tour description here.

The basement covers 49 acres, from 42nd to 97th street. The entire City Hall building could fit into its depth with a comfortable margin of room to spare. Today, the MTA is in the midst of an ambitious project to bring Long Island Rail Road trains into the terminal via the East Side Access Project, making Grand Central even larger and deeper.

These will be the deepest train tunnels on earth, at 90 feet below the Metro North track and over 150 feet below the street. It will take 10 minutes to reach these tunnels by escalator, at their deepest point.

Next, take a look inside Grand Central’s lost and found and discover 12 beautiful works of art in the terminal! Read on for the Top 10 Secrets of the Chrysler Building and the secrets of the Flatiron Building.

Subscribe to our newsletter