Exploring New York’s Industrial Past in "Cathedrals of Industry"

Join photographer Michael L. Horowitz for a journey through 50 years of photographs!

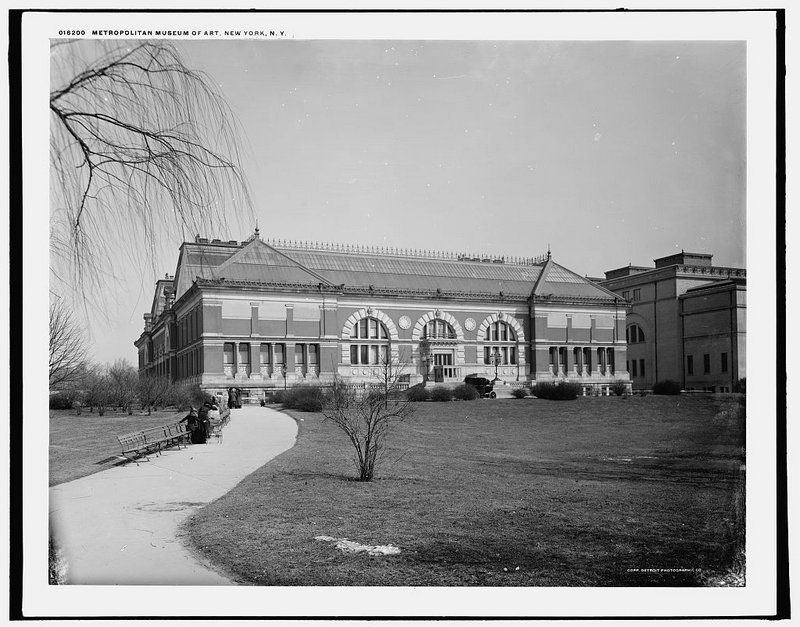

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is home to an unparalleled art collection, for which guides abound, but this list of secrets will explore how the Museum as a building is like none other in the city. It’s about its architecture, its rich history, and the hidden gems to look out for on your first, second, and umpteenth visit to the museum. Rather than one building, the Met is more like a jumbled collection of wings and various building campaigns. Over almost a century and a half, several prominent architecture firms played major roles in the museum’s growth, while many others also had a hand in the countless modifications, renovations, and additions that make the Met what it is today.

The first Metropolitan Museum of Art was located in a brownstone at 681 Fifth Avenue. Next, it was moved to a mansion at 128 W 14th Street. Both were temporary locations until a permanent facility could be built. A Central Park location for the museum was first hinted at in 1869 by publisher George P. Putnam, but the designers of Central Park – Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux – were opposed to the construction of public buildings within their carefully crafted naturalistic landscape.

Eventually, they conceded one spot in the park under the condition that any large buildings placed there would be “seen from no other point of the Park – while the whole of the territory thus enclosed was too small for the formation of spacious pastoral grounds.” [Morrison H. Heckscher, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Architectural History”]. This spot was the current location of the museum along Fifth Avenue. You can see original plans for the museum on the Met’s website.

When construction began on the museum’s new location at Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street, the area was significantly north of what was considered “desirable” during that era. In fact, it was predominantly farmland, far from the mansions of the old money set and new robber barons. The grid plan was already laid out, but the streets weren’t yet paved that far north.

Calvert Vaux (with Jacob Wrey Mould) was given the commission to design the first wing of the museum. The Medieval Hall (Gallery 305), which is in the center of the museum complex today, was the first wing built and is now surrounded by extensions on all sides. It was completed in 1880, and the interior looked very different than what we see today. The Romanesque-style interior that present-day visitors know actually dates from a 1930’s renovation. (Secrets of the Met tour leader Patrick Bringley told Untapped New York that the Mona Lisa was once displayed in the Medival Hall in the 1960s, and guarded by a custodial worker who ended up stealing small items from the musem’s collection!)

You can still see Vaux’s original Victorian Gothic façade in various places, like in the Robert Lehman Wing (Gallery 961/962). Originally, the façade pictured above would have looked onto Central Park. In the second-floor passage that leads from the Grand Stair south towards the Impressionist wing (Gallery 690), you can catch another glimpse of the original façade peeking out. This elevation once faced east towards 5th Avenue.

The unique cast-iron staircases flanking the east end of the Medieval Hall, rarely used but publicly accessible (from Gallery 304), are also remnants from the original Vaux building. Theodore Weston and Arthur Lyman Tuckerman added a wing to Vaux’s original building in 1888, and another in 1894. The Petrie Sculpture Court (Gallery 548) exposes Weston’s south façade and the grand portal that was the main museum entrance from 1888 to 1902. During this period, visitors entered off of the park from an entrance drive, rather than from 5th Avenue as today.

The tour guide of Untapped New York’s Secrets of the Met Museum Tour, Patrick Bringley, spent ten years as a museum guard, and he let us in on a “backstage” secret. The “backstage” areas of the Met are located underground below the galleries. Art and people travel through these underground passageways as they conduct the business that keeps the museum running. There has also been room for recreational spaces, including a shooting range in the 19th-century.

According to a New York Times article from 1935, construction of the shooting range was part of a larger renovation project at the Museum with funds from the WPA. The article states that the gallery will have “targets, lockers, and all appurtenances necessary for the annual shooting contests held by the guards who watch over the museum.” These annual matches had already been taking place for several years in an improvised gallery space. You can uncover more backstage stories from the Met in Bringley’s forthcoming memoir, All the Beauty in the World.

Famed architect Richard Morris Hunt was hired to design a grand 5th Avenue façade for the museum as part of a new master plan put forth in 1894 but died before construction began. This famous façade that visitors have known as the Met’s main entrance since 1902 was completed by his son, who carried out the design to almost all of his father’s specifications.

Thirty-one pieces of sculpture were originally designed for the façade, but a lack of funds left piles of uncarved stone atop the columns. These piles have since become an “accepted part of the façade.” [Heckscher] In Hunt’s original design, the four columns were to be topped by sculpture groups representing “four great periods of art: Egyptian, Greek, Renaissance, and Modern. Between each pair of columns sat a niche where Hunt intended to set a copy of one great work from each historical era.” [Gregory Gilmartin] After 117, the niches were finally filled in 2019 by a series of sculptures created by Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu. New art commissions now rotate through this previously unused space.

The neoclassical façade of the American Wing, curiously built into the wall of Engelhard Court (Gallery 700), was actually a freestanding building facing an exterior garden for fifty years. It was enclosed in 1980. The facade was rescued from the Branch Bank of the United States, located on Wall Street, before that building’s demolition in the 1920s.

The two Beaux-Arts bronze lampposts that stand in Engelhard Court once flanked the Bank façade. These were the original lampposts Richard Morris Hunt designed for the Met entrance. They are strategically placed in the Court, highlighting the ambiguity between nineteenth-century American art and its European influences. Another secret of the American Wing is that Englehard Court was once an openair courtyard. One of the design principles shared by the original and subsequent designers of the Museum–Vaux and Mould, Richard Morris Hunt, and McKim Mead and White–was to use courtyards to provide natural light. Over time these have all been filled in. With the advent of and preference for electric lighting and air conditioning, it was “no longer necessary to have interior courtyards [to] serve as light wells and air shafts.” [Heckscher]

The Chinese Garden Court (also known as Astor Court, Gallery 217), located in the Asian Art Wing, is a recreation of an authentic Ming Dynasty garden from Suzhou. Built into a space that was once a light well to the Egyptian galleries, it was one of the first Chinese gardens to be made outside of China. When the Garden opened in 1981, its koi pond contained twenty-six fish from Suzhou. Each fish represented one of the twenty-five workers, and one chef, who traveled to New York to build the garden. It took this group five months to complete their task, using hand-crafted materials like wood, ceramic, and stone.

Though it seems like a simple space, the garden is full of intentional architectural elements and meaningful symbols. For example, the ceramic drip tiles at the edge of each roof are embellished with various Chinese characters such as “Shou,” which means long life. Every twist and turn brings a new view, as described in this Met Museum video.

McKim, Mead, and White designed the fourth phase of the museum, extending Hunt’s façade along 5th Avenue to the north and south. The architects pushed for a floor-to-floor height that was greater than Hunt’s by almost a half-floor. As you walk around the museum, look out for the staircases and ramps (particularly in Asian Art and Ancient Near Eastern Art on the second floor) that were installed to accommodate the variance.

In some stairwells, you’ll see office entrances midway between floors and strange gallery entrances off the beaten path, like the Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gallery. Adapting the Met for handicapped access has also created idiosyncratic half-floor situations, like one that can be found in the American Wing.

The Temple had a long journey to the museum which started in 1965 when the Egyptian government gifted the Temple of Dendur to the United States government. It took nearly ten years to get to American shores. The Dendur exhibit at the Met opened in 1994. Uncover more secrets of this unique space here!

One of the most celebrated additions by Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo is the wing housing the Temple of Dendur (Gallery 131). You can enjoy a little-known elevated view of the Temple and Roche’s grand space from the Japanese Art Reading Room (Gallery 232) on the second floor of the wing.

It can seem at times like the Metropolitan Museum is a sort of architectural Frankenstein, put together by various different wings and pieces of entirely different buildings. Even parts of the collection have become entwined with the building’s architecture. Take these copper-plated iron stairs found between the first and second floors of Engelhard Court.

These stairs were rescued from the 1893 Chicago Stock Exchange building in Illinois. The stairs were removed from the building during its demolition in 1972. The mix of geometric and organic plantlike forms could be found in ornamentation throughout the Louis Sullivan design structure and are typical of his designs.

Could you imagine the entrance to the Met without it’s giant staircase? Well, those stairs (a favorite hang-out of Blair Waldorf and Co. in Gossip Girl), weren’t part of Richard Morris Hunt’s design. Expanded in the 1970’s by Kevin Roche, the massive steps were once considered an “overbearing ornament.” The steps were also thought to “strike terror in all persons who have reached middle age,” so various plans were drafted to do away with them including one, from the mid-twentieth century, to accommodate the automobile.

Originally, the Fifth Avenue entrance was designed to have a narrow set of steps leading from a vehicle drop-off. At some point later a “dog house” type vestibule was added to prevent drafts into the building. Both the original stairs and the vestibule were removed when the current stairs were put in.

Many members of the Met’s security corps, which consists of over 500 guards, are also working artists. You can see the work of some guards featured in Sw!pe magazine, a magazine of artwork, literature, poetry and criticism by guards at a variety of New york City’s cultural institutions. The magazine was initially conceived as a forum to feature artistic works of guards just at the Met, but now the magazine hopes to expand all across the globe.

Museum guards have access to artwork that many artist can only dream of. Spending hours and hours in the museum, guards develop intimate relationships with the works they protect. You can order a copy of Sw!pe Magazine here, and check out the work they create.

Next, check out 10 Sexy Secrets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

This article was originally written by Michelle Young and updated in October 2022 by Nicole Saraniero.

Subscribe to our newsletter