Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

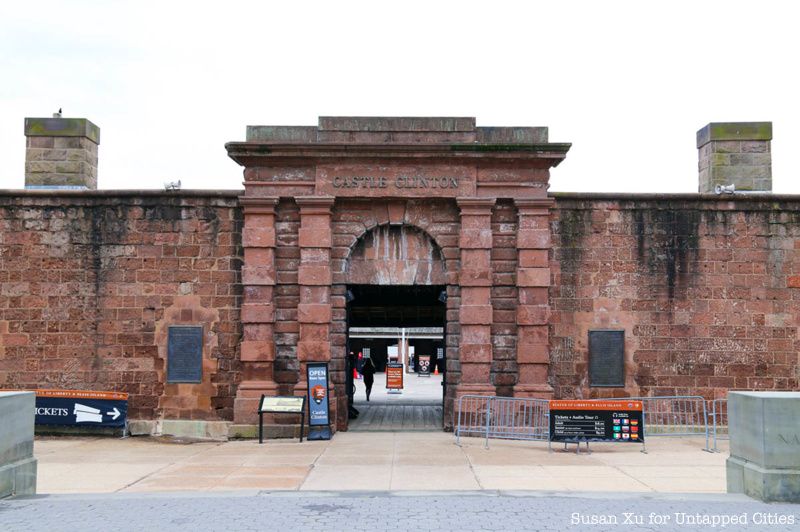

“Castle Clinton stands where New York City began,” writes the National Park Service website. Located at the southern tip of Manhattan, the sandstone fortification — also known as Fort Clinton — was initially one of four constructed forts intended to prevent a British invasion in 1812. However, its reputation is cemented as America’s first immigration station. Prior to Ellis Island, it welcomed more than 8 million people arriving to the United States between the years 1855 to 1890, and it’s been repurposed as a beer garden, theater and public aquarium over the course of its life.

Today, the National Monument continues to welcome visitors to New York Harbor. As the departure point for guests who join us for our hard hat tour of the abandoned hospital complex at Ellis Island (which you purchase tickets for below), Castle Clinton has continuously peaked our interest. You may also have seen it prominently featured recently in the new show The Alienist.

Here, we delve into 10 of its most interesting secrets and fun facts, covering its two century long lifespan:

Behind-the-Scenes Hard Hat Tour of the Abandoned Ellis Island Hospital

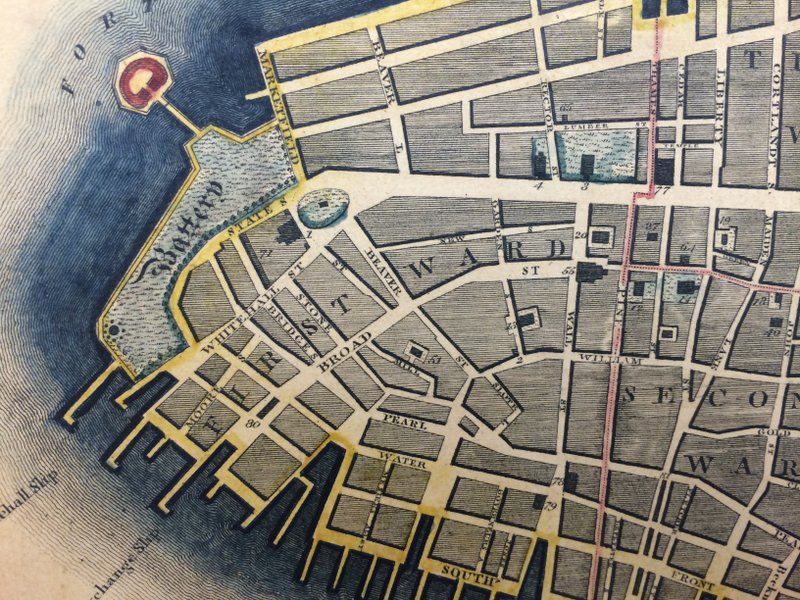

Castle Clinton on top left, as an island as mapped in the Commissioner’s Grid of 1811. Original map is located in the Library of Congress, photographed by Untapped Cities above.

According to an 1808 original plan for Castle Clinton, the fortification was originally built on a landfill isle that was constructed on a stone foundation. A 200-foot wooden causeway and drawbridge connected the fort to the Battery Park mainland, effectively turning it into an artificial island. Landfill, however, eventually expanded Battery Park, and the fort was later incorporated into Manhattan. Thus, it’s one of New York City’s many man-made islands.

Canons on display at Castle Clinton today

As we previously mentioned, Castle Clinton (originally known as the Southwest or West Battery) was one of four forts constructed to defend New York City from British forces during a period of increasing tensions that would eventually culminate to the War of 1812. Along with Castle Clinton, the other three fortifications — Castle Williams on Governors Island, Fort Wood on Bedloe’s Island (known today as Liberty Island) and Fort Gibson on Ellis Island — were intended to keep the British Navy at bay.

Castle Clinton was fully equipped with 28 cannons that could shoot 32-pound balls up to 1.5 miles away. However, it never actually had the opportunity to fire upon the enemy in any war. In 1817, it was renamed from the Southwest Battery to Castle Clinton, in honor of Dewitt Clinton, Mayor and later Governor of New York.

Aerial view of Castle Clinton. Photo by National Park Service NPS.gov.

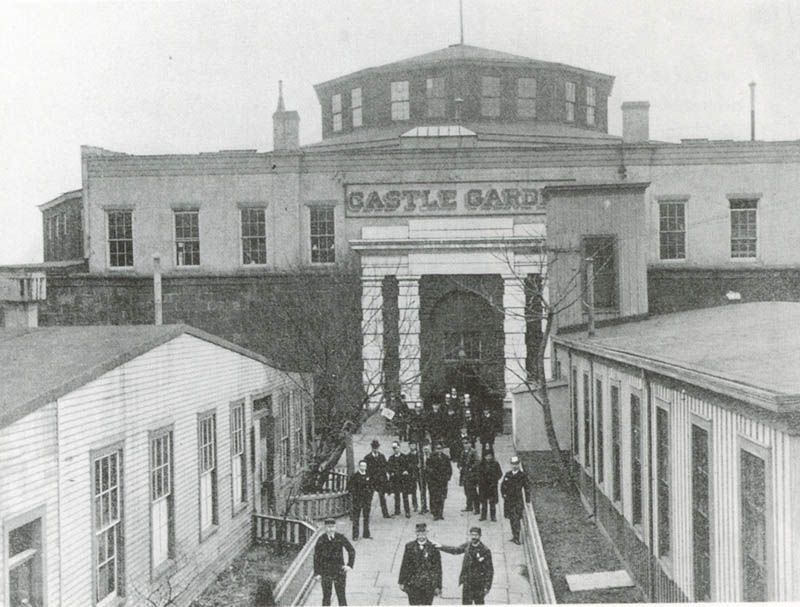

Before it became an immigrant processing center, Castle Clinton temporarily served as entertainment center between the years 1823-1854. It was deeded to the city in 1823, and was renamed Castle Garden, which featured a beer garden/restaurant, and later, an opera house, theater and exhibition hall. During its short-lived tenure as one of New York City’s most popular entertainment centers, it played host to notable visitors like Opera singer, Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale,” who made her American debut there in 1850, as well as European dancing star, Lola Montez, who performed her “tarantula dance” on site.

Additionally, many new inventions were demonstrated at Castle Garden, including the telegraph, Colt revolving rifles, steam-powered fire engines, and underwater electronic explosives. To accommodate such performances and showcases, a domed roof was placed over the structure in 1845.

Castle Clinton served as an immigrant landing depot between the years 1855-1890, during which an estimated 8 million immigrants (and up to as many as 12 million) arrived to Manhattan. The nation’s first such entity, Castle Garden was operated by the state until the U.S. government decided to move the center to Ellis Island, which was more isolated, and therefore better suited to protect people from the spread of diseases like cholera and smallpox. Quite tragically, most of Castle Clinton’s immigrant records were destroyed in a fire that took place on Ellis Island in 1897.

However, we do know of a few noteworthy immigrants who passed through. This includes Mary Mallon (Typhoid Mary), the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of a typhoid fever pathogen, inventor Nikola Tesla, illusionist and stunt performer, Harry Houdini, anarchist political activist and writer, Emma Goldman, newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, and Friedrich Trumpf, who would go on to build a real estate empire that was eventually inherited by his grandson, Donald Trump.

Immigrants arriving to the Castle Garden immigrant depot. Image via Wikimedia: Public Domain

Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews who settled in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries pronounced Castle Garden as “Kesselgarten.”

The word would eventually come to serve as a generic Yiddish term for a noisy, confusing or chaotic situation, or where a “babel” of languages were spoken — this, of course, was in reference to the many languages spoken by the arriving immigrants from around the world.

In 1896, Castle Garden reopened as New York’s first municipal aquarium, described by an 1897 Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine article as a 20,000-square-foot building with “graceful archways”, a glass-paned roof, and tanks surrounded by plants and shrubs where “his majesty, the whale, swims and blows as only whales can; a rookery for the sea-lion, and a pond for the seals, complete the central view.”

To make sure the structure was suited to house an aquarium, architects McKim, Mead & White had to alter it again prior to its opening. The oldest continually operating aquarium in the United States, it eventually became one of the city’s most popular attractions, bringing in 5,000 guests per day (and 2.5 million visitors a year) thanks to 150 housed specimens, exotic fish and beluga whale that lived there. However, when the attraction shut down in 1941, the fish were temporarily relocated to the Bronx Zoo, and the New York City Aquarium itself was relocated to Coney Island.

While many of Castle Garden’s immigrant documents were lost in the aforementioned fire, we can still sift through materials related to the creation, history and preservation of the structure thanks to the Manhattan Historic Sites Archive. Funded by the National Parks of New York Harbor Conservancy, the archive is the result of a three year endeavor to catalog and digitize collections related to six National Park Service sites in Manhattan (Castle Clinton, General Grant National Memorial, Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace, Federal Hall, Saint Paul’s Church and Hamilton Grange National Memorial).

The archives contain a rich catalogue of materials ranging from photographs to letters, as well as maps and prints. Explore it here, and discover period illustrations of Castle Garden, with 19th century lithographs and photographs documenting the aquarium, nationalization files, and even administrative records spanning the early 1700s to the late 1900s. Additionally, you can find Battery’s store of digital copies at castlegarden.org and at the National Archives; Atlas Obscura also offers up genealogical websites stevemorse.org and immigrantships.net, where searchable manifests from Castle Garden’s immigrant vessels are held.

Although Lower Manhattan is not typically the place you’d expect to find wildlife, Castle Clinton and the surrounding Battery Park area is home to a some surprising species. Alongside brown rats and grey squirrels, the critters you typically associate with the city, you can spot red-tailed hawks, peregrine falcons, and color kestrels. Most notably, the park was once home to Zelda, a wild turkey that lived there from 2003 to around 2014. At the time, she was believed to be the only wild turkey in Manhattan.

Named after Zelda Fitzgerald, the wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald, she quickly became a beloved fixture at the park, garnering a loyal fan base over the years. Sadly, however, it was announced that Zelda had been found dead in October 2014, following an automobile collision down South Street, near Pier 11.

In 1941, master urban planner and Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses, decided to shutter the New York Aquarium in order to make way for a bridge that would span from Brooklyn to the city. However, public outcry from preservationists put a stop to this plan in favor of a tunnel instead. Moses had to move the aquarium to Coney Island, and he attempted to dismantle Castle Garden in the process, disassembling its roof and stripping away its ornate floors. All that was left over from was the fortress’ original walls.

In the face of this initial demolition, preservationists intervened yet again, stopping Moses from completely destroying the fort. In 1946, it was designated a national monument, and was later restored to its original form in the 1970’s. Following the rejection of his Brooklyn Battery Bridge proposal, Moses reverted back to his original plans to construct the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel (aka Hugh L. Carey Tunnel). So from 1940 to 1952, portions of Battery Park were closed while the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel was being built beneath them. Also, check out the secrets we dug up about the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel.

As an expert on fortifications and a senior officer in the Army Corps of Engineers, Colonel Williams, a grandnephew of Benjamin Franklin, was the principal force behind the design and establishment of Castle Clinton and Castle Williams (named after the Colonel).

Completed in 1811, the structure was not built beyond its first tier of 28 casemated gun positions, and featured eight foot thick walls, which are the only original part of Castle Clinton, as all the other sections have been reconstructed. Although the fortification was never actually utilized, Colonel Williams originally designed it to provide crosshair fire with Castle Williams (East Battery) so that the channel between them could be closed.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Abandoned Hospital Complex at Ellis Island and Fun Facts About Ellis Island.

Subscribe to our newsletter