Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Today, controversial bill Intro 775, which may limit the effectiveness of the NYC Landmarks Law, goes to hearing in the City Council Chambers at City Hall. This got us thinking: while most New Yorkers know of City Hall, a landmarked building completed in 1811, fewer visit or know the history of the city’s main government building. Here are 10 of our favorite secrets about City Hall:

The Bridewell on the west side of City Hall was a combination workhouse, jail and prison. Named after the prison in London that was converted from the palace of Henry VIII, New York City’s Bridewell was so important, it was labeled on the Commissioners’ Plan for 1811 that laid out New York City’s street plan.

Its most notorious reputation came from during the American Revolution, when it was a British controlled prison. Construction on Bridewell began in 1775, a year before the Revolution, and the British didn’t bother to finish the prison. Prisoners reported that there were no panes in the windows to keep out the cold and conditions were likely similar to those in the sugarhouse prisons nearby. An almshouse and a barracks, whose archaeological remnants are partially below the Tweed Courthouse, were also located in what is now City Hall Park.

Image by Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants

Now located in NYC’s Archaeological Repository, this hollow, cylindrical object made of mammal bone was initially thought to be a spice grinder or needle case, but was later determined to be a douche dating to somewhere between 1803 to 1815. It was found in a garbage pile three feet underground on the north side of City Hall. Archaeologists believe all the items in this pile may come from one “celebratory event.” According to archaeologist Lisa Geiger, women across social classes gave them as wedding presents to each other, though the use and effects were somewhat misguided.

Also at the Archaeological Repository are a bayonet from the barracks and buttons from the almshouse. One of the industries taught at the almshouse once located at City Hall was button making, in the hopes to turn around those that could not care for themselves. Finally, bones were found on the site during the 1990’s renovation of City Hall.

George Washington used this desk when it was located in Federal Hall, the first capitol building for the United States and where Washington was inaugurated as President. The building was demolished in 1812 and replaced by the Federal Hall National Memorial we see today on Wall Street. This desk was moved to the Governor’s Room in City Hall in 1844 and has remained there. Atop the table is imprinted the words “George Washington’s Table 1789.” As recounted in this article, the desk has been widely copied as a desirable piece of furniture for the country’s elite.

Photo by franklyfrank

To New Yorkers’ chagrin, New York’s City Hall loses the title of “oldest continuously used city hall in the nation” to the city hall in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Even so, Mayor Bloomberg claimed such following a 2007 renovation of City Hall–that it was “the oldest and longest serving city hall in the nation.” However, the Perth Amboy building purportedly still has remnants of its 1767 structure, which did house rooms for city governance.

The New York Times contends that though the archaeological artifacts got much more air time, “far more valuable treasures are secreted away inside City Hall itself: the city’s little known but extensive collection of 19th-century portraits and other artwork, which is rarely seen by the public that owns it all.” In total there are more than 108 portraits of New York dignitaries by painters like Thomas Sully, Rembrandt Peale, John Trumbull, Charles Wesley Jarvis, and John Vanderlyn.

Through a non-profit he founded, Mayor Bloomberg raised $1.7 million for the restoration and conservation of the collection, but Mayor de Blasio angered many when he began to take down some of the paintings as part of a greater plan to add ethnic diversity to the art collection.

The portrait of Lafayette is on the right wall, closest to the balcony

Samuel Morse, better known as the inventor, was also a fine arts painter and was a founder of the National Academy of Design, where he served as president. In 1825, he was offered the commission by the Common Council to paint the Marquis de Lafayette, in celebration of Lafayette’s year long visit the United States for the 50th Anniversary of the American Revolution. Lafayette was then, the only surviving general of the war. As a passionate American nationalist, this “was likely the pinnacle of [Morse’s] career,” writes Barbara Maranzani for History.

To understand the context of the critique, you also need to think about the time. It was the era of Tammany Hall, with corruption rampant. Residents saw City Hall as a “bottomless pit” of taxpayer dollars (a reader letter published in the New York Gazette), the New York Evening Post felt that the construction project should be “suspended,” and in 1893 the New York Times supported a demolition of City Hall.

Meanwhile, the Tammany political ring wanted power and was plotting to be incorporated into the machinations of New York City government, partially through the architecture of City Hall. Tammany politicians began to support those that favored the demolition, relocation or expansion of City Hall.

In 1872, the Tweed Courthouse was built, mostly with graft, just behind City Hal and the political ring had a building of its own. Then in 1894, New York State passed a bill prohibiting the demolition of City Hall, ending the debate.

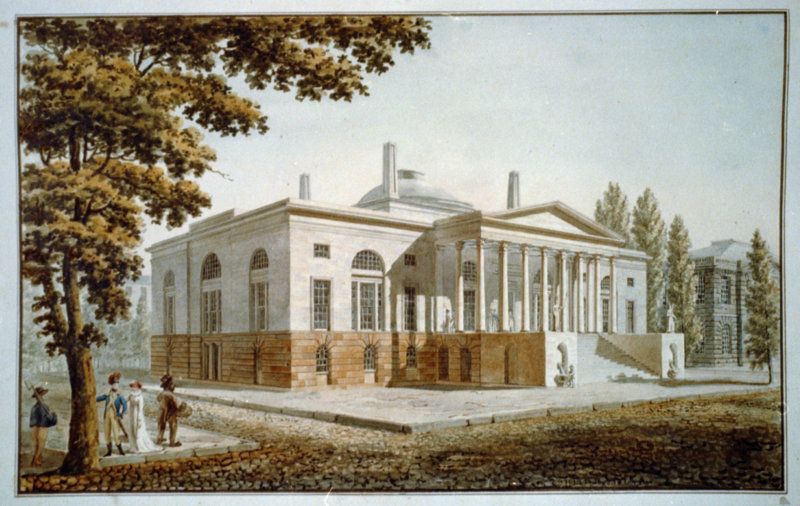

A proposal for City Hall by Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Image from Library of Congress.

During the debate about the merits of City Hall, there was an architectural competition for a new one. The architect Charles B. Atwood had already throughly studied City Hall, with the idea that it may one day need to be expanded or renovated. He found out about the City Hall competition a day before it was due, but in that time completed the full set of drawings needed. Missing one requirement of the competition, his entry was eliminated but because his design was deemed superior, he was given a special prize and permitted to fully complete his work later. The above drawing from 1903 is from a later proposal, after Atwood’s death, for an expanded City Hall.

The current dome, with its coffered ceiling, was added in 1912, a little over a century after the completion of City Hall in a restoration by Grosvenor Atterbury – but it is actually the third dome to be in this space. The first was destroyed in an 1858 fire when fireworks were set off the roof. Atterbury replaced the dome with a structure of concrete, and lowered and widened the dome.

10 corinthian columns support this dome and the rotunda below is where Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant both lay in state after their deaths. It was only in 1976, when City Hall was deemed an interior landmark that the rotunda became open to the public and protected from alterations.

Opened in 1904, the old City Hall station with its beautiful architecture and curved platform was intended to be a showpiece of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company’s (IRT) new subway line. It was also the chosen place for hanging the commemorative plaques dedicated to those who designed, built and financed the underground train system. Contrary to popular belief, there was no plaque here honoring Alfred Ely Beach’s early pneumatic subway.

The station was closed just a few decades later in 1945 because its curved platform wasn’t able to accommodate the IRT’s newer, longer cars. Today, the subway stop still remains closed but you can get a quick glimpse of the platform by taking the 6 train past its last stop at Brooklyn Bridge. The stained glass windows, blacked out during World War II, can also be seen from the grounds of City Hall Park. For those who want a full-blown tour, you can become a member of the MTA Transit Museum to access the City Hall station.

Read about 10 fun facts from opening day of the NYC subway.

Photo by __macgyver

A warped mirror in the Governor’s Room (similar to one seen in the Women’s National Republican Club near Rockefeller Center) was made that way to diffuse candle light throughout a room

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of the Woolworth Building, just across the street. Get in touch with the author @untappedmich. See more photos inside City Hall here.

Subscribe to our newsletter