Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

In a city known for its towering skyscrapers, the American Radiator Building commands attention with its unique black and gold facade. Located on 40 West 40th Street in Midtown Manhattan, it was conceived by architects John Howells and Raymond Hood for the American Radiator Company, a successful business trust, which consolidated a number of North American radiator and boiler manufacturers in the late 1800s.

Today, the twenty-three story tower has taken on new life as the Bryant Park Hotel, but its history — from its construction in 1924 to its present-day status as a center of hospitality — is not forgotten. Here are 10 secrets we uncovered about the iconic structure.

Very fittingly, the American Radiator Building was designed to resemble the company’s signature product: the radiator. The black brick is said to represent coal, and the entire structure — when lit up at night by its floodlights — has been compared to “giant glowing coal.”

With its dramatic appearance, the building essentially came to serve as advertisement for the American Radiator Company. Architect Raymond Hood, however, has denied the claim that the symbolic effect was intentional.

In 1922, the Chicago Tribune hosted an international design competition for its new headquarters, offering $50,000 in prize money for the best entry. Of the 260 submissions received, Howells’ and Hood’s neo-Gothic design was selected as the winner, although many perceived the second-place design, by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, to be the best.

Following his win, Hood became “instantly famous,” and a simple job designing radiator covers for the American Radiator Company eventually turned into a larger commission for its eponymous showroom and office building. Saarinen’s design, however, left a lasting impact — lending itself to emulation over the years. In fact, the American Radiator Building’s structural form is based off his unbuilt entry, and Hood himself has even acknowledged Sarrinen’s influence on its design, naming him among the architects who gave his team a “lift over many rough places.”

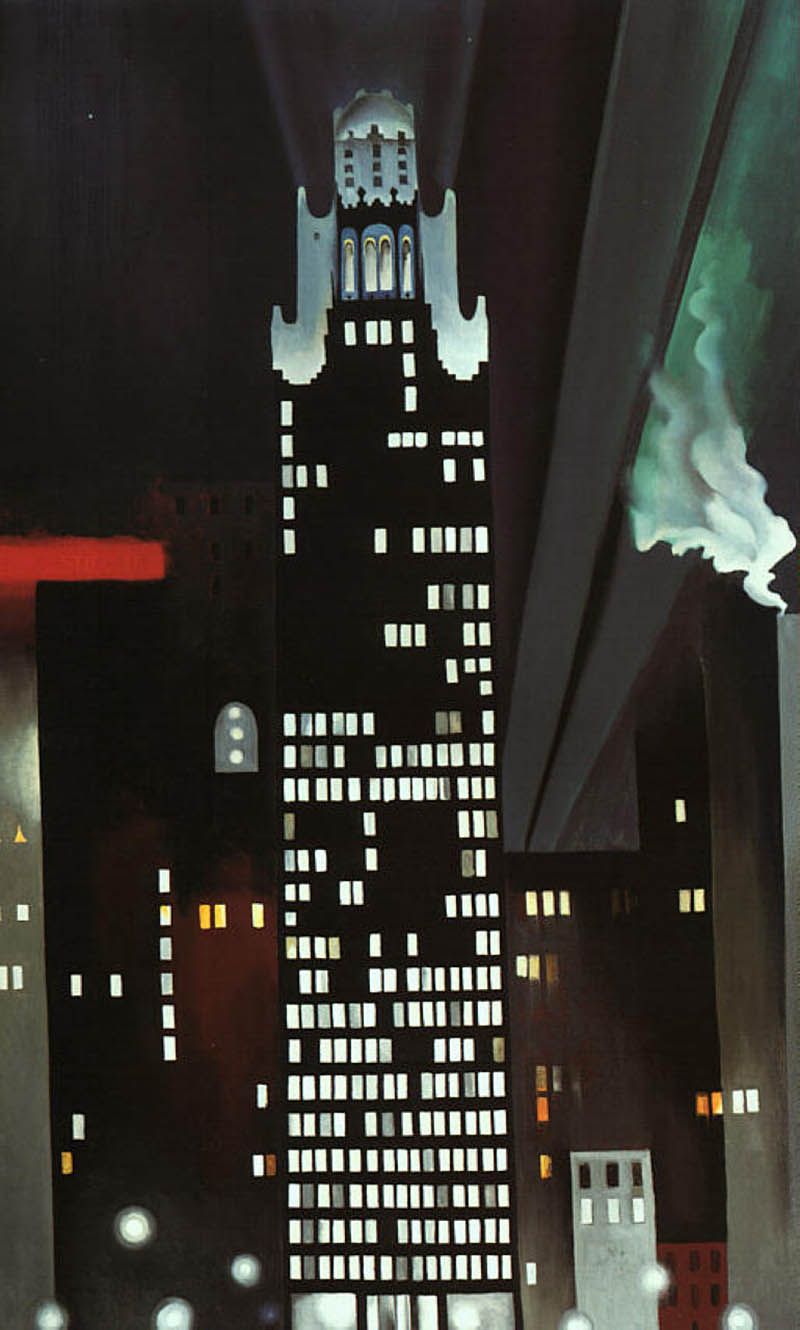

“Radiator Building — Night, New York” (1927) by Georgia O’Keefe. Image via WikiArt

Three years after the American Radiator Building opened, American artist Georgia O’Keeffe painted “Radiator Building — Night, New York,” one in a series of images depicting New York cityscapes. O’Keefe — who was “taken by the glow of the building after sunset” — depicted the building lit up at night by its floodlights, as seen from the vantage point of her high rise studio on the thirtieth floor of the Shelton Hotel at 49th and Lexington.

Also, read about nine other artists inspired by the early skyscrapers of New York City.

The basement of the American Radiator Building was originally designed as a large showroom, where boilers, furnaces and other heating products were showcased to the public. In 1929, following a merger between the American Radiator Company and the Standard Sanitary Corporation, the showroom was renovated to display plumbing wares and bathroom fixtures.

Today, the vaulted tile ceilings of the former showroom can be seen inside Bryant Park Hotel’s Cellar Bar, a gothic cavernous lounge known for its specialty cocktails.

According to The New York Times, Hood disliked the typical office building facade, which was usually punctuated by dark glass windows that looked like black holes. The resulting effect made most structures look like a “waffle stood on end,” he explained.

To counteract this, he purposely opted for black brickwork when designing the American Radiator Building. The material lessened the visual contrast between the walls and the windows, giving the tower “an effect of solidity and massiveness.” Interestingly enough, despite its solid brickwork, the Landmarks Preservation Commission notes that the main shaft of the tower does not have a monolithic quality due to subtle varieties in wall surfaces, Hood’s use of gold accents and the setbacks (or step-like recessions in walls) that are associated with Art Deco architecture.

One of the most unique features of the American Radiator Building is the fact that over 90 percent of its floor space is within 25 feet of a window. Hood specifically designed the structure to be free standing, as opposed to other skyscrapers in Manhattan, which often share walls with adjoining buildings. This allowed a lot of light to flood into the structure, but it also meant that elevators took up much of the interior space as the typical floor area within measures only 5,600-square-feet. To mitigate this, Hood implemented automatic leveling and push-button car gates to allow the elevators to operate more efficiently.

The American Radiator Building, following its conversion into the Bryant Park Hotel, now houses 130 rooms and a 73-seat movie theater with black leather seats. The sub-basement screening room is a popular fixture of the hotel, but building it was no easy feat. The construction team had to dig 45 feet into bedrock as the water table in the surrounding area was quite high due to displacement caused by the subterranean book stacks of the New York Public Library located beneath Bryant Park.

According to project manager Constantine Fotos, a series of pumps and underground drainage systems were implemented in order to build the theater — and “not a swimming pool.” The excavation process caused a seven-month delay in the hotel’s opening.

Read more about the New York Public Library’s subterranean stacks here.

The American Radiator Building is the first New York skyscraper to feature dramatic exterior lighting. Because Hood did not want lights to be turned on after dark, he directed that the building’s upper floors be illuminated with floodlights. The visual impact made the structure “one of the sights of the city” at night, attracting the attention of passing pedestrians.

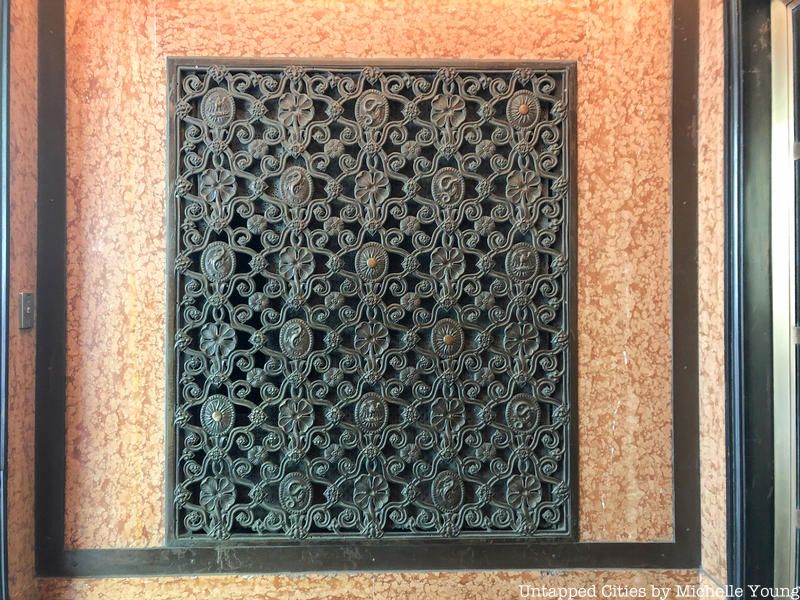

Aside from its distinctive brickwork and gold accents, there are quite a few decorative elements of the American Radiator Building that are worth noting — from its gilded terra cotta ornaments that crown its tower to its four-story base that is sheathed in black granite and bronze. Look closely at this base and you may notice carved allegories sitting on top of it. They are said to be sculpted allegories of matter transforming into energy — quite fitting for a company that once specialized in heating products.

Sculptor Rene Paul Chamberlain, who also worked with Hood on the Chicago Tribune Building and the Daily News Building, was tasked with crafting all of the gold-glazed sculptural reliefs.

In 1998, the American Radiator Building was sold for $15 million to Philip Pilevsky, the CEO of real estate company and property developer Philips International. The building was later converted into The Bryant Park Hotel three years later, which cost an additional $50 million to complete.

Due to structure’s landmark status, the renovation of its facade required special attention. All of Hood’s exterior features (including the black brick, gold detailing and lighting) were restored and the black marble and mirrors, once found in the lobby, have been replaced. However, some proposed changes — such as bigger guest room windows — were prohibited. The building, as a result, still retains its original detailing, in addition to its bronze and marble entrance on 40th Street.

Next, check out 10 Artists Inspired by Early Skyscrapers of New York City and Downtown Doodler: American Radiator Building ArchiDoodle.

Subscribe to our newsletter