NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

Today marks the 134th year since the Brooklyn Bridge officially opened on May 24, 1883. In honor of this special occasion, we spoke with Joanne Witty, attorney, environmentalist and co-author of the book, Brooklyn Bridge Park: A Dying Waterfront Transformed

, who played an instrumental role in the creation of the surrounding green space.

As the former president of the Local Development Corporation that developed the park’s master plan, Witty witnessed the transformation of the waterfront site from a desolate area to a thriving attraction that serves both the community and visiting tourists alike. The process, as she reveals in an interview, has not “been easy.” The 85-acre waterfront park “reflects the multitude of hands and minds that were applied to the creation. It is not precisely the park that any one person would have made, nor could it be,” she writes in her book, co-authored with Henrik Krogius.

Here, she shares unforeseen challenges, insider details and surprising secrets about the process of creating what is now regarded as one of the largest and most significant public projects to be built in New York City.

Also make sure to join us for our Secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge Walking Tour, which will delve into the epic origin behind this iconic New York City span. We’ll discover Brooklyn Bridge’s many secrets, including its old Cold War fall out shelter, its love locks, the Russian fur vaults and the bridge jumper survivor’s support group.

The Secrets of Brooklyn Bridge Walking Tour

Although the Brooklyn waterfront once thrived as a port and trading post, maritime activity declined as the twentieth century progressed. By the mid-1980s, the ships were gone and the piers, which the Port Authority had acquired from the New York Dock Company, were under utilized.

In response to the waning activity, the Port Authority decided to sell its land to private developers, which would be set aside for commercial and real estate projects like high-rise housing and parking lots: “…the piers were a liability, an added cost, without prospect of significant continuing revenue,” writes Witty.

However, public out cry arose against these plans, leading to the establishment of not-for-profit organization Friends of Fulton Ferry Landing (now Brooklyn Bridge Park Coalition), which advocated for the creation of a park. Although it would take years of negotiation, the Port of Authority finally agreed to allow its property to be developed as self-sustaining public parkland in 2000.

During the negotiation process for Brooklyn Bridge Park, the Port Authority argued that the focus should be placed on private investments and economic activity, with recreational uses taking a backseat. On the other end of the spectrum, the Brooklyn Heights Association favored a project that was “fundamentally all-park,” with limited private development.

To emphasize and bring to life the idea, the association sought the help of landscape architect Terry Schnadelbach, who produced illustrations of a passive green space with commercial facilities (to be known as Harbor Park). Schnadelbach, who was inspired by Hudson River School painters, Frederick Law Olmsted and “a little” Robert Moses, described his vision as an “American landscape” of “natural elements, long beautiful curves, shaded sitting areas, waterfalls, and fountains for kids to get wet.”

The proposal never came to fruition as the Port Authority did not believe it would provide enough of a financial return.

A self-proclaimed Brooklynite, Tony Manheim zealously advocated for the construction of Brooklyn Bridge Park. Due to his tireless efforts, he eventually became the point man for the Brooklyn Bridge Park Coalition and adopted the nickname, the “founding father of the park.”

Interestingly, his vision was mostly green and largely passive. Although he saw some potential maritimes uses for the site (with plans for outdoor playing fields), he largely advocated for a green space reserved for reading, sitting and walking — not roller-skating and other activities that take place today.

Borough President Howard Golden — unsatisfied with the Harbor Park concept — produced his own plan for the “Brooklyn Harbor Market,” which he believed would retain the industrial character of the site, promote economic activity and appeal to the residents in the surrounding communities.

Although his plan was not realized, he envisioned a market where “vendors will sell ethnic foods from knishes to kielbasa and from roti to ravioli; fresh foods including fish, fruits and vegetable; and goods that are prepared on-site such as baked goods, beer confections, arts and crafts.”

In order to ease the qualms surrounding private development, the park portion of the Brooklyn Bridge Park was built first when construction began in 2007.

“…we wanted to reassure people that we were not a private developer; we were a private entity,” Witty explained. “We were building a park, and we were only building enough housing as we needed, on the edges, in order to pay for the maintenance of the park” (which currently adds up to $15 million per year).

In summary: “no housing, no park,” Witty states.

In 2005, Brooklyn Bridge Park’s rain structures were found to be in such terrible shape that there were pulled up to avoid maintenance costs. This is why you will see a lot of “soft edges” in the park instead of “bulkheads,” which Witty describes as a “hard structure” that looks out above the water.

A soft edge, on the other hand, is comprised of rocks (riprap), which is lower and closer to the shore. This unique feature makes the park different from other green spaces in the city, as it allows visitors to “really feel the water.”

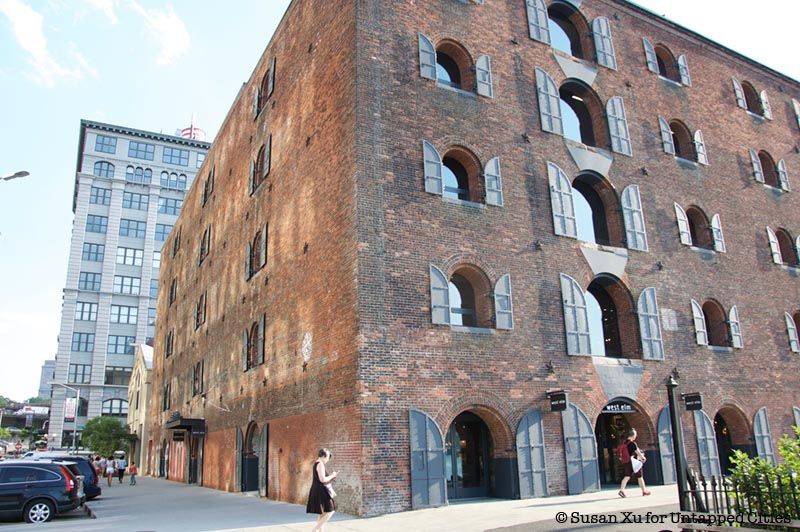

Empire Stores

Due to its engineered topography, Brooklyn Bridge Park fared better than many other waterfront parks when Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012. However, in the aftermath of the storm, extra measures were taken to fortify the space in response to changes in city Building Codes, which were put into effect by Mayor Bloomberg and the City Council.

Designed to mitigate future damage from coastal flooding, the new regulations mandated that buildings be constructed from a higher base with all mechanicals and electricity housed above the new flood plain line. This policy was applied to all of the park’s development projects, including Empire Stores, which had its ground floor dug out and replaced with a concrete slab, and the Tobacco Warehouse, which was designed to meet the standards of “wet” flood proofing (assumes that water will flood into the building with minor damage after drainage).

Also, check out our behind-the-scenes look at the construction of Empire Stores.

When a critic objected to the thirty-foot hill on Pier 1, which blocks ground-level views, Landscape Architect Michael Van Valkenburgh said that it was a frugal way to create landscape interest — particularly in the middle of the site, which Matt Urbanski, a principal at Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc., has described as a “boring place—a complete flat stretch of concrete.”

“You want to known why we put the hill on Pier 1?,” Van Valkenburgh asked. “Because we could. I mean that, because it’s the only pier that isn’t on a structure, and therefore you can pile up something heavy, and it’s not going to break the bank, which was a huge issue for this project all along.”

The hill, which catches storm water and creates microenvironments within its slopes, was constructed out of the rock that was being excavated for the construction of a Long Island Railroad tunnel under Manhattan.

During the design and construction phase of Brooklyn Bridge Park, when the site was still being assessed, miles of wood were uncovered in a cold storage building at Pier 1, which was slated to be demolished.

The wood was salvaged and used for park benches, park buildings and most notably, light poles. While most parks in New York City utilize modern copies of nineteenth-century cast-iron fixtures, the wooden light poles in Brooklyn Bridge Park are simply fitted with “subdued spotlights,” which draw back to the site’s industrial past.

One relic that has remained untouched in Brooklyn Bridge Park is a small forest of wooden piles that can be found on the south side of Pier 1. The piles are remnants of a former pier structure, whose platform was removed as the park was being constructed. According to Brooklyn Bridge Park: A Dying Waterfront Transformed

, the pilings were allowed to remain as a fossil of the park’s history.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Brooklyn Bridge Park and the Top 10 Secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Subscribe to our newsletter