5th Avenue in 1905. Image via Wikimedia Commons

There are plenty of books by writers who arrive in New York City, make it their home, and start chronicling it – amazed, amused, appalled, daunted, delighted, frustrated. And, most of all, viewing the city, to quote William Styron, as “a place as strange as Brooklyn.”

This is a list of fiction by native New Yorkers, writers who came of age in one of the city’s five boroughs, writers who lived out their childhoods in a world made of concrete, and writers for whom the strange place is the norm.

10. The Custom of the Country, Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton wrote about the New York City community that she grew up in, which remained a part of her for the rest of her life. Marriages were business deals, and the marriages of the fabulously named Undine Spragg, who arrives in New York City from the fictional Mid-Western city of Apex, all turn into failed business deals. Seeing early 20th century New York City through the eyes of the city’s upper classes is both eerie and amusing. Washington Square and West End Avenue won’t do for Undine; she’s set her sights on Fifth Avenue. Wharton, like us, seems to be strangely comforted by the unhappiness of the people who occupy those districts — always aspiring, never satisfied.

9. Daddy Was a Number Runner, Louise Meriwether

Children playing in Harlem in about 1930. Image from National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

Every New Yorker who’s read this gripping, autobiographical novel set in Depression era Harlem can recount a scene that has haunted them ever since. Mine is this: The twelve year old protagonist, Francie Coffin, wants to sit up and read but has to fend off an infestation of rats with her “usual supply of weapons…. a hammer, a screwdriver, and two hairbrushes.” Whenever Francie hears a noise, she throws the ammunition to chase the rats back into their holes . When she runs out of things to throw, she gives up, puts her book away, and goes to bed.

8. Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, Grace Paley

The woman who started a story with the words, “You would certainly be happy to meet me,” wrote three collections of short stories about the day-to-day lives of New Yorkers managing to get by: living together, living alone, raising children, and lying awake wondering how they were going to pay the bills, but never ever taking themselves too seriously. In a voice that’s tough and gum-crackingly New York City, with observations of neighbors in parks and the hallways of apartment houses, through scenes on sidewalks and in subways, Paley makes you see things in New York City that everyone else ignores. It is the perspective of a writer who, later in life, explained that she didn’t write more because “I happen to love being in the streets.”

7. The Wanderers, Richard Price

Macombs Road in 1960. Image from Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

The opening scene of Richard Price’s first novel is a character’s careful parsing of warring gangs in the Bronx in 1962. Price has been called “the greatest writer of dialogue, living or dead, [America] has ever produced,” and this novel is a testament to that. You can hear Richie, Eugene, and Buddy arguing in the playgrounds at night, bargaining with one another as they make their way down the Dion sound-tracked streets, weighing their options and how and whether they’ll get the hell out.

6. Ragtime, E. L. Doctorow

New York City in 1908. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Doctorow’s novel about America shortly before World War I doesn’t take place only in New York City, but the city is the vortex of its orchestrated chaos — riots erupt, fat cats make deals, revolutionaries campaign, cops launch racist attacks, a musician is unjustly jailed, a tenement family parent nurses a sick child, the beginning of the film industry is glimpsed, a high profile murder trial is underway, and the show always goes on. Meantime, shakers and movers of the era appear at pivotal points: Harry Houdini performs airplane stunts for Franz Ferdinand, Emma Goldman gives Evelyn Nesbit a back rub, and Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung ride into the tunnel of love together in Coney Island. Drink up.

5. The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, Oscar Hijuelos

The Mambo Kings – brothers Nestor and Cesar Castillo – flee Batista-era Havana to settle down on La Salle Street on the edge of Harlem. Nestor’s New York-born son narrates the story of their exploits in 1950s New York City after both Nestor and Cesar are dead. At the centre of that story is an encounter with another Cuban migrant-turned-New Yorker, Desi Arnaz, who provides The Mambo Kings with their greatest success — an appearance on I Love Lucy as Ricky Ricardo’s Cuban cousins. Mambo Kings was the first novel by a Latino to win the Pulitzer Prize. The New Yorker judged it “a story so utterly American that it’s a wonder we haven’t heard this particular version of it before.”

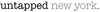

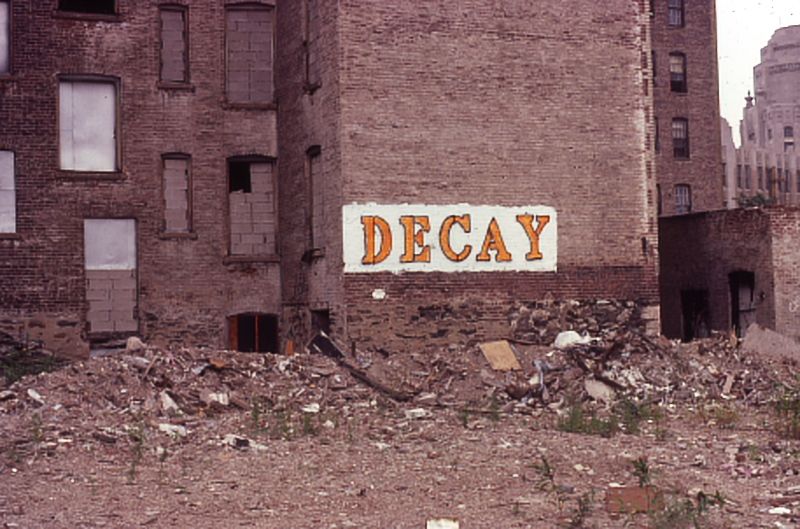

4. The Boy Without a Flag, Abraham Rodriguez

The South Bronx in 1980. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Abraham Rodriguez’s first collection of fiction is set on the fire-scarred streets of the South Bronx in the 1980s, after the planned shrinkage of the city planners cuts off public services to low-income areas of New York City. A teenage girl is pulled off a sidewalk into a van and disappears, children play in the ruins of gutted buildings, and in the title story, a Bronx-born student refuses to pledge allegiance to the American flag at school. These stories about how life continued in a part of the city that officialdom tried to abandon are mesmerizing, with glimpses of tenderness appearing among the day-to-day brutality.

3. For Rouenna, Sigrid Nunez

There are few books that chronicle the experiences of women who served in Vietnam. For Rouenna is one of them. Rouenna, who grew up with the unnamed narrator of this story, served as a combat nurse – her nights blood-filled as she tends injured soldiers, days adrenaline-pumped caring for boys who’ll soon die, intimate connections available instantly with other military personal at the front line. When Rouenna dies, a suicide without warning, it is up to the narrator to tell her story. For Rouenna is also about class stratification and class mobility in America, how both Rouenna and the narrator navigate their escapes from the Staten Island housing project where they grew up and how they leave “the forgotten borough” for lives somewhere else.

2. The Intuitionist, Colson Whitehead

Colson Whitehead’s best known novel doesn’t take place in New York City, but in an unnamed city in a retro parallel universe where one of the most prestigious professions is that of elevator inspector. Both the unnamed skyscraper-choked city and Manhattan would not have grown the way they did without elevators of course. The Empiricist school of elevator inspectors rely on mechanical expertise to ascertain faults, while the Intuitionists can sense whether or not something’s wrong. Lila Mae Watson, the first African American woman to be promoted to elevator inspector, is an Intuitionist. When an elevator she’s just inspected goes into freefall, she finds herself at the centre of a Noir-style labyrinthine investigation focused on finding out what led to the disaster.

1. Motherless Brooklyn, Jonathan Lethem

A private eye with Tourette’s Syndrome, raised in St. Vincent’s Home for Boys, is the narrator of this novel set in Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill in the late 1990s. Lionel Essrog, between involuntary exclamations, is determined to find out who killed his mob-affiliated mentor and boss, Frank Minna. Lethem’s many New York City novels all manage to capture the grit and wonder, the squalor and magic, of New York City in different ways. What Lethem conveys so perfectly in this one is how provincial life can be a world capital. Lionel has lived his entire life without leaving New York City, until the investigation takes him beyond the city limits.

Next, read 5 Authors Who Crafted Novels Around the Culture and Influence of NYC and 8 NYC Homes of Famous Writers from Truman Capote to Edith Wharton.