Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

In 2014, the town of Wetzlar, Germany celebrated the return of iconic lens and camera manufacturer, Leica, which was founded 100 years ago in this manufacturing enclave outside Frankfurt. The headquarters, shaped like a camera lens, offers both a look behind-the-scenes into the intricate production process of Leica cameras, as well as an exhibition space that celebrates the company’s illustrious history.

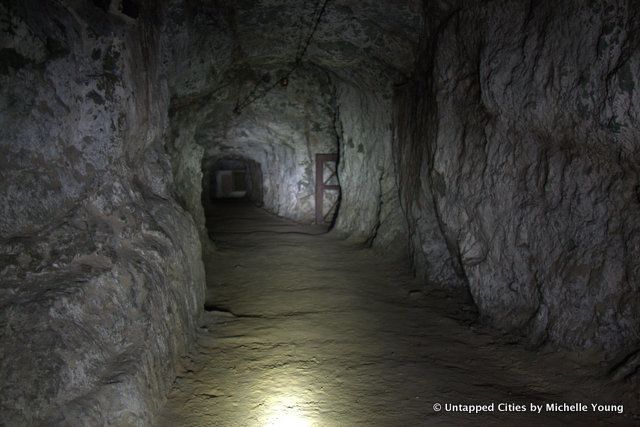

While attending the opening of the new Leica headquarters, we also learned some of the secrets of the company from the staff. One, which particularly caught our attention, was the tunnel system in Wetzlar that enabled Jewish Leica (then the Leitz company) employees to escape Nazi-controlled Germany in the late 1930s. Known by Holocaust historians as the “Leica Freedom Train,” this initiative of Dr. Ernest Leitz II and his daughter Elsie Kuehn-Leitz have all the hallmarks of a Schindler’s List-like story, but remains mostly unknown to the global public. During our trip, we were able to visit the tunnels with a local tour guide.

The only access to natural light in the tunnel is at the very top of this ladder

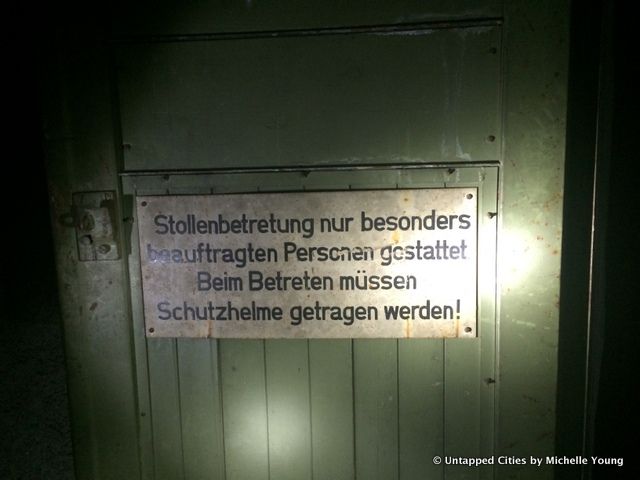

The vast system of tunnels was originally dug to support the iron ore being mined in Wetzlar from 1842 to 1928. The tunnels remained empty until 1944, when Allied bombardments necessitated the move of Wetlzar’s factory production, many of which were essential to the German war effort, underground. Leitz was one of the companies that moved into the tunnels, as an indispensable supplier of rangefinders and other optics to the Germany military. The German weapons V1, V2 and V3 were also produced in these tunnels.

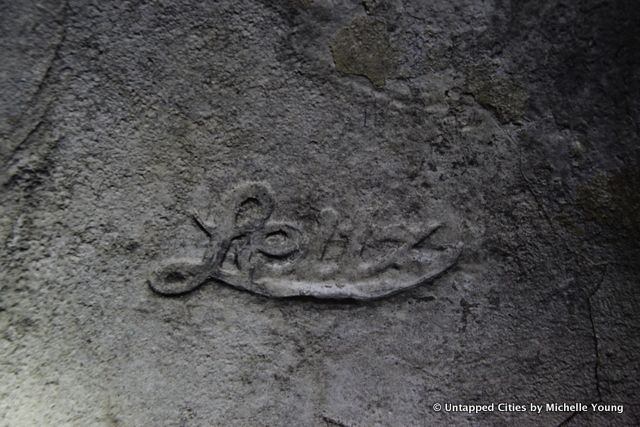

Engraved Leitz company logo inside the tunnels

Entrance to the tunnels under a park along the Hausertorstraße in Wetzlar

On the photography-end, compact cameras like those pioneered by Leica, were considered key to the propaganda effort. In fact, on August 1, 1937 Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda, decreed that “photojournalists who do not understand that the use and promotion of small modern cameras constitute a duty inherent to their mission should remove their official photojournalist armbands.”

Thus, on the outside the Leitz company was operating as a model German industrial company, acquiescing to government production orders. It also accepted European prisoners of war and female Ukranian slave laborers, who worked in the tunnels and lived in camps under tough conditions. At the same time, Leica had always subscribed to an enlightened worker policy–offering health care, sick leave and pensions–likely as a strategy to recruit and retain skilled workers for the complex optics industry.

The end of a tunnel where dynamite holes can still be seen

Cigarette papers are still inside some of the dynamite holes

During the 1930s, Dr. Ernest Leitz II used his unique position to move at least 45 German Jews out of the country, along with assisting 23 people to avoid punishment for laws that condemned inter-racial marriage. In many cases, Dr. Leitz offered multi-year apprenticeships in the Leitz factory in Wetlzar, which made the workers suitable for work transfer to Leitz’s overseas agencies–most went to New York City. In addition to funding the travel, Dr. Leitz personally provided continued financial support for the refugees by transferring money overseas through the Leitz company and other methods. Those that Dr. Leitz assisted ranged from friends, Leitz workers, to those whose cases were presented to him.

The Nazi leadership and the Gestapo were certainly aware of some of Dr. Leitz’s activities, though his refugee effort came to a forced end after the Nazi invasion of Poland, which closed off Germany’s boundaries. In the research done by Rabbi Frank Dabba Smith on the role of Dr. Leitz, he writes that Dr. Leitz joined the Nazi party in 1941, on recommendation by the mayor of Wetzlar in order to “stave off proceedings against him.” Dr. Leitz himself feared that German authorities would remove him from leadership, particularly since there were no Nazi party members among the company leadership.

In a post-war “Denazification” trial, Dr. Leitz was exonerated from his Nazi party affiliation, but the dual, contradictory activities of both Leitz the citizen and Leitz the company, have left an incongruous record to this day.

The work of Rabbi Smith, which focuses on the testimony and records of those rescued, has resulted in a post-humous Courage to Care award from the Anti-Defamation League for Dr. Leitz. The long delay has much to do with the desires of Dr. Leitz and his family to keep the story quiet. His son Gunther asked that nothing be published about the Leica Freedom Train in his lifetime, stating “My father did what he could because he felt responsible for his employees and their families and also for our neighbours. He was able to act because the government needed our factory’s output. No one can ever know what other Germans had done for the persecuted within the limits of their ability to act.” The first article to be written about Dr. Leitz’s humanitarian work was published only in 1999, followed up the research by Rabbi Smith.

In many ways the research is just beginning, as noted by Rabbi Smith, who includes a lengthy list of other cases of support from Dr. Leitz II. The role of the tunnels, as both military industrial site and escape routes, could benefit from further research. In the meantime, here are a few additional photographs from inside the Wetzlar mine tunnels.

Get in touch with the author @untappedmich. Get a behind-the-scenes look inside the new factory and headquarters of Leica in Wetzlar.

Subscribe to our newsletter