Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

The streets of New York City were particularly empty on the morning of January 14, 1971. Many might have assumed it was due to the extreme cold — with a mix of rain and snow, it was a quintessential bitter January day. However, the city’s streets, avenues, and alleys were missing a key fixture that New York’s expect to see: the NYPD. From January 14th through January 19th, 85 percent of the city’s police officers went on strike, leaving the city with only 6,500 non-striking patrolmen, detectives, sergeants, and lieutenants to give New Yorkers the sense that their city was still being policed. However, while the statistics might seem daunting, the most important thing about the 1971 Police Strike might be just how unimportant it felt.

On paper, the strike’s cause was merely a matter of wages. Officers were arguing that they were owed $100 a month for the preceding 27 months under a contract provision setting their pay at a ratio to that of sergeants. When a case addressing the matter was declined by the courts, officers lashed back by organizing a wildcat strike (a strike not officially recognized by a union). On the morning of January 14th, thousands of policemen called in sick to their precincts, a widespread case of the ‘blue flu’ that marked the beginning of New York’s five days without a police force.

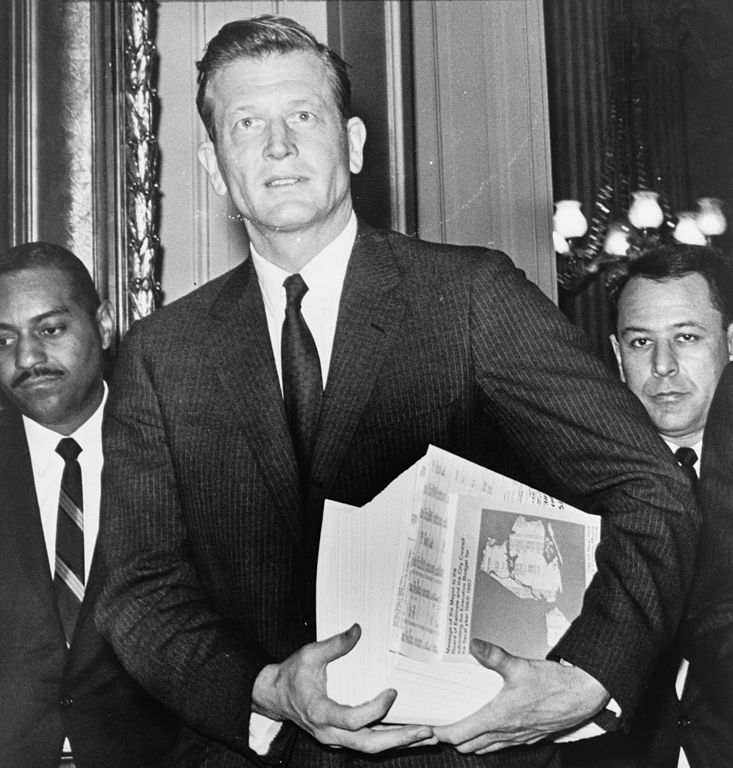

Mayor Lindsay was blamed by many NYPD officers for their woes. Photo from Library of Congress

Mayor Lindsay was blamed by many NYPD officers for their woes. Photo from Library of Congress

However, the pay parity issue was merely a boiling point for a larger cultural issue that was deeply rooted in the NYPD. Many officers believed that they were victims, taken advantage of by the city and its leadership while being simultaneously blamed for the city’s ills. These views were made evident by interviews conducted by the New York Times with angry officers. “Other unions of city employees – transit, teachers, sanitation – went on strike and, far from being punished, won fat contracts,” said one officer, possibly referring the recent transit strike of 1966. Other officers blamed Mayor Lindsay for their woes, claiming that he only cared about his political ambitions (he briefly ran for president the following year) rather than the needs of officers.

In some cases, members of the police went so far as to blame their poor reputation on a widespread conspiracy that included academia and the media. “The liberal establishment, particularly in the academic world, had the attitude that the policeman was guilty and had to prove himself innocent,” said one officer. “The bass media has been unfair,” said another, “distorting the corruption of a small number of policemen and ignoring the good work of the vast majority.” The strike, while technically the result of a payment dispute, became an opportunity for policemen to vent long building frustrations, although this did not necessarily mean acknowledging their own faults. In summation, one officer said, “despite years of insults such as ‘pig’ from radicals at campus outbreaks and other demonstrations, policemen who tried to maintain law and order won little support.”

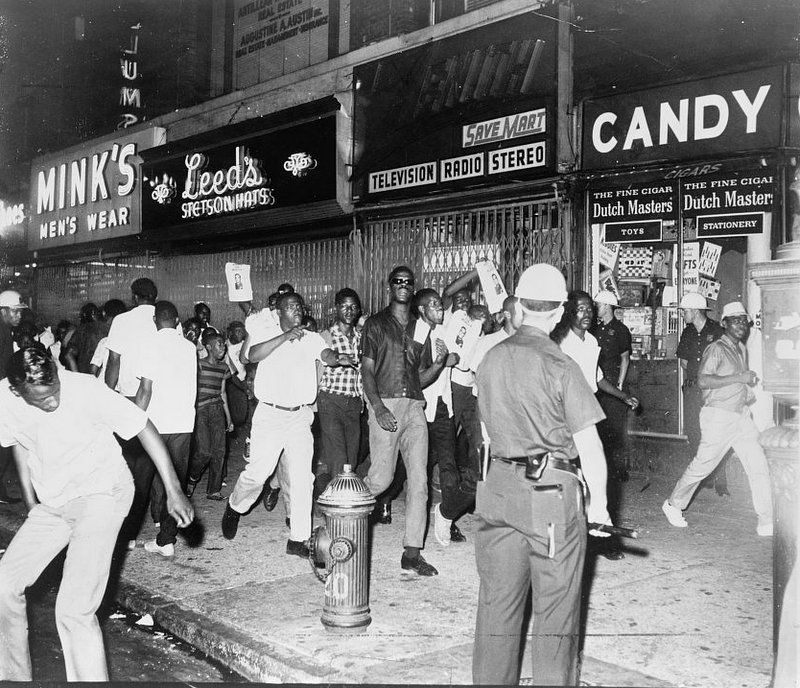

The 1964 Harlem Race Riots. Following the killing of James Powell, people took to the streets carrying the photo of Lieutenant Gilligan. Photo by Dick DeMarco for World Telegram & Sun from Library of Congress.

The 1964 Harlem Race Riots. Following the killing of James Powell, people took to the streets carrying the photo of Lieutenant Gilligan. Photo by Dick DeMarco for World Telegram & Sun from Library of Congress.

However, the critiques officers faced were not without merit. Throughout the 1960’s and the beginning of the 1970’s, the NYPD experienced widespread and highly publicized corruption (famously dramatized by Al Pacino in the film Serpico). Police violence had also rattled the city, including the 1964 Harlem Riot which resulted from the killing of James Powell, a 15-year old African American by a veteran officer. While some officers perceived themselves as victims of a vast conspiracy, a great number of New Yorkers saw the police as an institution that had a negative impact on the city.

When interviewed by the New York Times, one young man from the Lower East Side said “every time I see a cop he’s holding somebody up against a car.” “The cops worry me when they’re working,” said another Lower East Sider. Similar sentiments of distrust and disillusionment were shared throughout the city. “Cops on strike?” said one elderly woman in the Bedford- Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. “I thought they went on strike a long time ago – like about 10 years.” Mrs. Walter Goray of Fresh Meadows, Queens made her priorities even clearer. “Maybe I’m being too brave,” she said, “but really, I’m more concerned about Con Edison breaking down.”

An old Squad Car at the Police Museum on Governor’s Island

The apparent calmness of these New Yorker’s was not unwarranted though. Over the course of the five day strike, there was no apparent increase in crime throughout the city. In fact, the only real differences noted by reporters were an increase in illegally parked cars and people running red lights, the actions of opportunistic motorists. Richard Reeves, writing for the New York Times, said “New Yorkers— ‘a special breed of cats’…went about their heads‐down business. There was no crime wave, no massive traffic jams, no rioting.” Some attributed all of this to Police Commissioner Patrick V. Murphy’s “visible presence” strategy of deploying superior officers and detectives in patrol cars in heavily populated areas, like Times Square. Others simply attributed it to the cold. However, the strike brought to light another very real possibility: maybe the city was able to function as normal with a much smaller number of police officers.

In the immediate aftermath of the strike, experts were already beginning to question the antiquated and ineffective methods of policing in New York City. Reeves continued in the Times: “Maybe police should be doing something different. At least, some knowledgeable people believe police should be taking a hard look at what they are doing and they might discover that what seemed sensible in 1871 should be changed in 1971.”

Officers at the recent demonstrations for George Floyd in front of the Barclays Center

The strike concluded on January 19th and resulted in no pay increase or compensation for officers. Yet while the strike may have been unsuccessful in realizing its immediate goals, it highlighted a larger cultural divide in New York City that remains unresolved. In the wake of George Floyd’s death and the resulting protests throughout the country, the hashtag “Defund The Police” has gained significant traction. The hashtag is not a call to remove police force entirely but to instead divert the disproportionate amount of cash these police forces receive relative to other parts of the city budget, to other things, such as education and healthcare. Such a change would significantly decrease the amount of police officers in the city, yet as the 1971 Police Strike demonstrated, that does not necessarily mean the city will be less safe. While the strike may have been surprisingly unimportant when it happened almost 50 years ago, that cold, fateful week in January continues to hold meaning, highlighting questions surrounding the practice and culture of police work that are prevalent in New York today.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of NYPD

Subscribe to our newsletter