Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

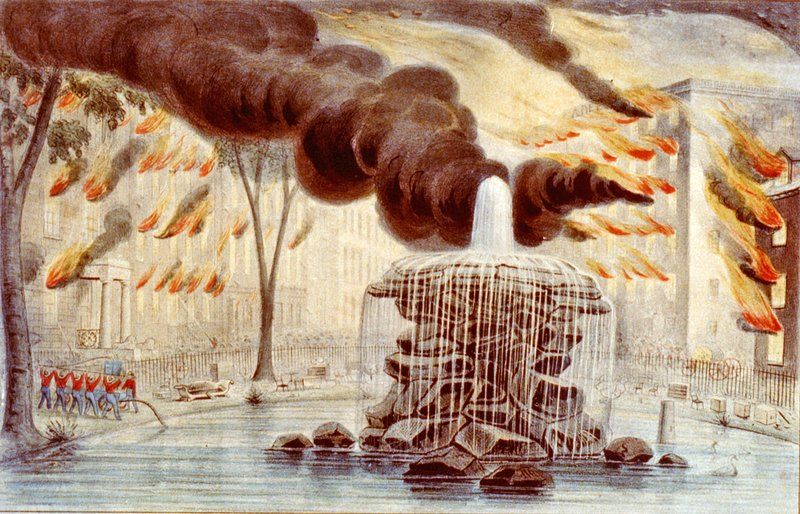

A Currier and Ives print of the Great Fire of 1845 burning buildings around Bowling Green Park. Image via Wikimedia Commons

On July 19, 1845 the third massive fire to devastate New York City hit the heart of the modern day Financial District. Although the fire didn’t cover as much ground as the Great Fires of 1776 or 1835, it did come with the greatest loss of life leaving 30 dead.

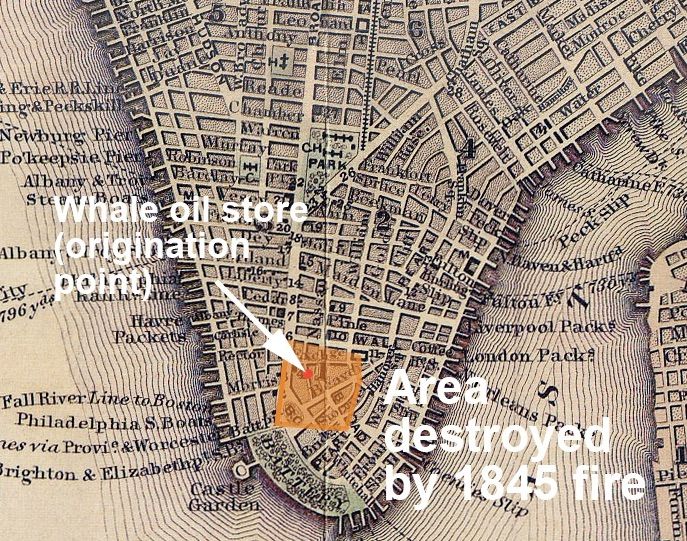

The fire started at 2:30am on the third floor of J.L. Van Duren Oil Merchant and Stearin Candle Manufacturers at 34 New Street. Because it was the middle of the night, it took nearly a half hour for officials to ring the City Hall alarm bell. By then the fire was spreading so quickly that firefighters were coming from Brooklyn and Newark to help put out the blaze.

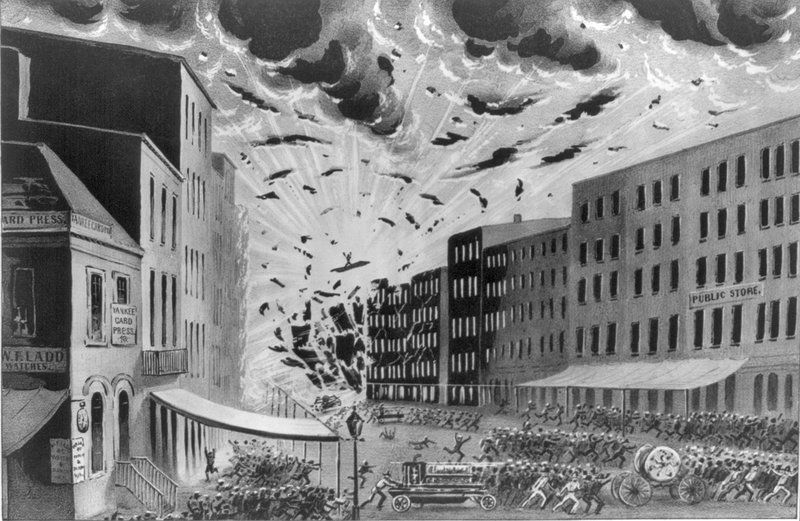

Somewhere between 3:30 and 4:00am, the Crocker and Warren warehouse on Broad Street caught fire. Unfortunately for just about everyone in the vicinity, it was filled to the rafters with saltpeter (potassium nitrate commonly used in firecrackers and gunpowder mixtures). Within moments it set off an explosion that was heard as far as Sandy Hook, New Jersey. The series of blasts leveled seven buildings, shattered every window within a mile of the explosion’s center and hurled debris and people through the air like rockets.

Print by Currier and Ives depicting the Crocker and Warren Warehouse explosion. Image via Wikimedia Commons

This account taken from Benson John Lossing’s History of New York City describes the scene:

“While these explosions were occurring the firemen of Engine No. 22 say they heard someone exclaim, ‘Run No. 22 for your lives; the building is full of powder!’ While most of them were in the act of running, a grand explosion took place, with a sound compared by one witness to a clap of thunder. It was accompanied with an immense body of flame, occupying all the space in Broad Street between Beaver and Exchange streets. It instantly penetrated at least seven buildings, blew in the fronts of the opposite houses on Broad Street, wrenched shutters and doors from buildings at some distance from the immediate scene of the explosion, propelled bricks and other missiles through the air… spread the fire far and wide, so that the whole neighborhood was at once in a blaze.”

Terry Golway’s book So Others Might Live: A History of New York’s Bravest, further describes how Engine No. 22 responded to the Crocker and Warren fire by immediately sending men up to the fourth floor to hose down the flames. Once the smoke became too thick the foreman ordered his men out of the building. One fire fighter by the name of Francis Hart Jr. was trapped inside collecting the hose so he ran up to roof and escaped by jumping onto a neighboring building. Immediately after his jump, a second explosion pelted Hart midair to yet another rooftop. Lucky for him, he only injured his ankle.

Others were not so lucky. The New York Daily Tribune reported that Augustus L. Cowdrey from Engine No. 42 was fighting a building fire next to the Crocker and Warren warehouse when the impact of the second explosion hit him head on. He was thrown so violently that even after a two-day search his body was never found. His name now appears on a volunteer fire fighter memorial in Trinity Churchyard.

After 10 hours of intense battling, the fire was extinguished inflicting almost $10 million in damage on lower Manhattan ($250 million at today’s value). It took the lives of four firefighters and 26 other New Yorkers. According to James Trager’s New York Chronology, practically every causality insurance company in New York was wiped out by the event.

There were a couple of phoenixes to rise from the literal and figurative ashes of the fire. Unlike the other two historic blazes where fire fighters struggled to find enough water to put out the massive blazes, the fire fighters of 1845 had an ally in the newly installed Croton Reservoir (you may remember it from last week’s column). Also, strict building codes enforced after the Great Fire of 1835 forced new buildings in Manhattan to be built of brick frames rather than wood. And it made all the difference. Although 345 buildings were destroyed, the area of destruction was more contained than the sweeping acreages destroyed in 1776 and 1835.

A map of the area destroyed by the fire. Map via Wikipedia Commons

Since its first iteration in 1648, the Fire Department of the City of New York was a volunteer organization. Men were not paid nor were they trained properly in fire fighting tactics. This fire heralded the creation of new fire safety and prevention measures. Within twenty years, the FDNY would no longer be a volunteer force and New York City would not see a fire of this magnitude again.

An interesting final coda: The original Delmonico’s Restaurant then located on Broad Street was a casualty of the 1845 fire. Lorenzo Delmonico replaced it with a new restaurant and hotel off of Bowling Green on the former location of New York’s first coffee house. But before all that it was the site of Martin Cregier’s tavern in Dutch New Amsterdam whose beer-drinking Dutch bowlers gave the park its name.

Next, check out 13 Fun Facts About the Original 1811 Commissioners’ Plan for NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter