Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

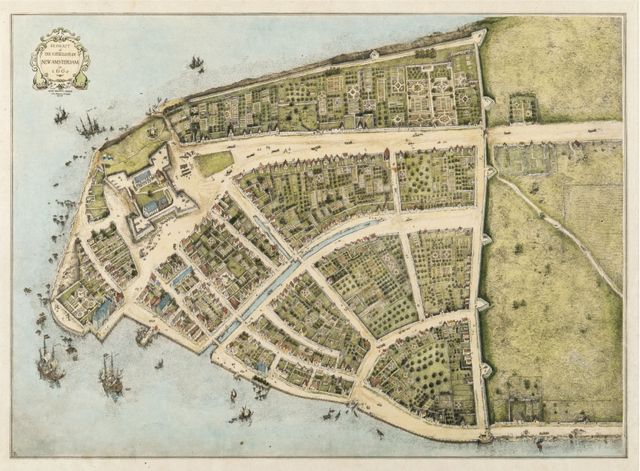

1916 Redrawing of The Castello Plan, map of 1660 New Amsterdam via Wikimedia Commons.

On May 4, 1626, Peter Minuit arrived in New Amsterdam as the new director from the Dutch West India Company. Minuit was in his early 30s, and had been sent to diversify the trade coming out of New Netherland, then almost exclusively animal pelts. Minuit means “midnight” in French (spoken by some of the Dutch), so if you prefer to think of Manhattan’s purchaser as “Peter Midnight,” go for it.

For more, join our Untapped Cities tour that traces the remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

Minuit (and his predecessor, Verhulst) was already authorized by the Dutch West India Company to settle any disputes with local Native American tribes over trading and land rights. Soon after his arrival, Minuit entered into a transaction with one or more local tribes over the rights to Manhattan. No original title deed remains, and the main documentary evidence is a Dutch West India Company internal communication from late 1626 that includes the following (translated):

Yesterday the ship the Arms of Amsterdam arrived here. It sailed from New Netherland out of the River Mauritius on the 23d of September. They report that our people are in good spirit and live in peace. The women also have borne some children there. They have purchased the Island of Manhattes from the savages for the value of 60 guilders. It is 11,000 morgens in size.

Nearly every other detail about the transaction must be inferred. Let’s dive in.

The Date: Edward Robb Ellis, who wrote the entertaining, if not entirely precise Epic of New York City, offers May 6, 1626, only two days after Minuit’s arrival in New Netherland. The Burrow & Wallace tome Gotham pegs the transaction as occurring in “May or June.” Historian Rob Howe’s post on the Gotham Center site claims “most likely in mid-May.” Some historians won’t concede this precision, but no one offers an alternative date.

Conclusion: The purchase made in May, 1626.

Minuit’s Partner: Ellis says Minuit met with “the principal chiefs of nearby tribes.” Gotham argues that it is impossible to say which of the local Lenape tribes Minuit met with. Historian Nathaniel Benchley seems more confident that Minuit was dealing with the Canarsees, a Lenape tribe principally located in south Brooklyn, led by Chief Seyseys. The Canarsees were happy to take whatever the Dutch were offering, Benchley claims, given that the Weckquaesgeeks, a closely related Wappinger tribe, actually occupied most of mid and northern Manhattan Island. Benchley’s theory is one explanation for the Native Americans in question accepted such a low price, and of course turns the whole notion of Europeans exploiting Native Americans on its head. Given the bloody skirmishes fought between Wappinger tribes and New Netherland settlers during the early 1640s (“Kieft’s War”), it’s obvious that not all Native Americans respected whatever deed was signed in 1626. Before Kieft’s War began, these tribes were living comfortably in the outskirts of New Amsterdam, still a tiny settlement with only a few farms north of Wall Street.

Lastly, there is a possibility that whoever signed the deal had a sense of the Europeans’ power, and agreed to such a deal out of fear or strategic alliance. We haven’t found any scholarly work pushing this theory, but I’m sure it’s out there, and we’ll adopt it for now.

Conclusion: We don’t really know who signed the deal, but it could have been the Canarsees, who didn’t have much of a footprint in Manhattan, rather than the Weckquaesgeeks, who lived north of the Dutch on the island.

The Cost: “Sixty guilders” is one of the few hard facts we have to work with. Many a blog post has been spent constructing how much that is worth today. The “$24” figure was first advanced by a historian in 1846. Since then, valuations are all over the map, getting as high as $15,000. To me, this is moot, since we can be pretty sure what the recipient tribes actually received, and it wasn’t an appreciating trust fund.

In 1630, the Dutch purchased Staten Island, also for 60 guilders value. A copy of the deed explained that the supplies offered to local chiefs in exchange for unfettered right to the land included kettles, axes, hoes, Jew’s harps (an old instrument), anddrilling awls, the last of which were essential for ramping up the manufacturing of wampum, the shell-beads that made up the local currency.

These items are often referred to as “trinkets”, which conjures images of tacky Times Square gift shops. In fact, these items were highly useful to local Native Americans. That said, their collective value was pretty meager, given that they were exchanged for large islands. Finally, it is worth myth-busting the notion that Manhattan was literally traded for beads.

Conclusion: Forget the exact modern dollar amount – Manhattan was acquired for a useful, but not particularly expensive set of European tools.

Buying or Leasing: One of the most common explanations of the 60-guilder price is that Native Americans didn’t have the same concept of land rights as Europeans. This 2002 law review article by Robert Miller makes a compelling case, however, that this is a misconception, one perhaps willfully misunderstood by generations of Europeans and Americans to lessen their guilt over blatantly seizing native land. While many Native American tribes did have communal land that belonged to that specific tribe, that land wasn’t other tribes’ for the taking, and even within tribes, certain families had rights and responsibilities associated with parcels of land not dissimilar to European capitalist constructs. Law professor G. Edward White similarly argues that local tribes had a tradition of property rights, and may have been simply offering the Dutch hunting rights.

Over at Gotham Center, Richard Howe notes that the Dutch, who relied less on brute force than their European peers, certainly thought the transaction was a full and legitimate title to the land, parceling it out over the succeeding years to private purchasers. Indeed, the Dutch West India Company continued to negotiate with the Lenape for parts of Brooklyn and Queens over the next few decades. (As well as that 1630 Staten Island purchase.) This is evidence that both sides knew what they were doing with the transaction, adding further credence to Benchley’s theory that not all of the interested parties (namely, the Weckquaesgeeks) were at the negotiating table.

Conclusion: We should not assume that whoever negotiated with Minuit thought to himself, “Hey, no one can really own land, man, let’s share with the Dutch.” Because Native Americans had an understanding of property rights, it is likely that whoever agreed to this deal didn’t have much to lose by it, or at least knew what they were doing.

—————————

Too Long / Didn’t Read

In May of 1626, Dutch West India Company rep Peter Minuit met with local Lenape Native Americans to purchase the rights to the island of Manhattan for the value of 60 guilders. We don’t know who signed the deal with Minuit, but it could have been the Canarsees, who didn’t have much of a footprint in Manhattan, rather than the Weckquaesgeeks, who lived north of the Dutch on the island. The exact value of 60 guilders in modern dollars is irrelevant – the transaction itself involved a useful but not particularly pricey set of European tools. (And not beads or junk trinkets.)

It is a misunderstanding of Native American property rights to think that Minuit’s trading partner thought to himself, “Hey, no one can really own land, man, let’s share with the Dutch.” It is more likely that the deal was amenable to the partnering Lenape, either because they had little at stake in Manhattan, thought they were retaining an interest in the land, or a combination of fear and political strategy counseled in favor of a deal.

And THAT is how the Dutch purchased Manhattan.

For more, join our Untapped Cities tour that traces the remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

For more NYC History, check out our Today in NYC History series here. For more from the author, check out his blog.

Subscribe to our newsletter