Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

On an otherwise calm September 16th in 1903, only a day and a half before the massive “Vagabond” hurricane devastated portions of the city, rival members of two notorious Lower East Side gangs squared off under the elevated platform of the Second Avenue train line. The lengthy and bloody gunfight that ensued was possibly the largest of its kind in American History.

In dispute was a narrow strip of real estate considered to be old New York’s premiere red light district – the Bowery. The largely Jewish “Eastmans,” named for their brutish, pockmarked leader, Edward “Monk” Eastman, held the territory south of 14th street and east of the Bowery. Paul Kelly, a charismatic former pugilist, ran the predominantly Italian “Five Points Gang” under the guise of a political club called the Paul Kelly Association. Five Points territory covered much of lower Manhattan west of the Bowery.

Enemies to the end, Kelly and Eastman clashed for years over control of the Bowery’s lucrative vice profits. The Rivington street fight was not their first violent confrontation, nor would it be the last.Nearly a hundred gangsters (most in their teens or early twenties) participated in the shootout and at least three men were killed. Many others were injured in the chaos amid what was described by newspapers as a “fusillade” of bullets. In the aftermath of the carnage, public officials faced hard questions about the brazen lawlessness of criminal organizations in Manhattan.

Herbert Asbury speculates in the book The Gangs of New York that the conflict began when Eastman thugs stumbled upon Kelly gunmen planning to hold-up a stuss (card) game that was under Eastman protection. Operating stuss games and robbing competing stuss games was a major source of revenue for street gangs of the era.

Contemporary papers place the start of hostilities at Livingston’s Saloon at the intersection of 1st Street and 1st Avenue, where at least one man was shot to death. The conflict spilled out into the street and a small gun fight broke out under the Allen Street arch of the Second Avenue El at Rivington Street. Messengers from both sides were dispatched to nearby gang headquarters to muster reinforcements.

Dozens of gunmen soon arrived and joined their compatriots who were shielding themselves behind elevated train columns. For four hours the gangsters exchanged near continuous fire as terrified residents and business owners boarded up their windows and barred their doors.

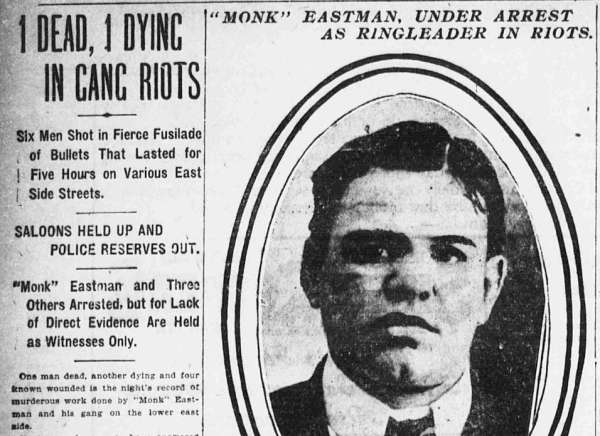

It wasn’t until gangsters started firing at responding officers that police reserves were called out to quell the fighting. As the gangsters scattered and sought refuge in nearby safe houses, police conducted a building by building search, eventually apprehending four men at No. 141 Allen Street. One of the men arrested was Monk Eastman himself.

As Michael Donovan lay dying in a Bellevue hospital bed from injuries suffered during the battle, police pressed him to identify his attackers. But in accordance with the code of the underworld he refused, saying: ‘I know who shot me, and when I get out, I’ll fix em’. An hour later Donovan was dead and Eastman was once again a free man.

The public outrage over the incident on Rivington Street signaled to politicians that the unconditional support of gangsters could not continue in its current form. After failed attempts to broker a truce between the two sides, Tammany Hall pulled its support of Eastman and Kelly. Police began cracking down on the city’s gangs, leading the arrest and jailing of many prominent gangsters, Eastman included.

In 1911, the Sullivan Act was passed making the concealed carry of unregistered firearms in the city a felony. Prior to the act possession of a pistol carried a ten dollar fine. The sweeping legislation was named for “Big” Tim Sullivan, a corrupt Tammany Boss of the Bowery and Lower East Side who had been a close associate of both Eastman and Kelly. Sullivan, who had his own private mercenary group, could now be assured that his own men were among the few legally packing firearms within city limits.

Over the next two decades, the nature of organized crime in New York City would change dramatically as the street gangs were gradually replaced by professional criminals who could no longer operate in public with impunity. John Torrio, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, and Al Capone would use the lessons learned during the Eastman/Kelly war to build criminal empires all their own.

Subscribe to our newsletter