Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Few conversations about New York City spark more heated debate than the redevelopment of Times Square. For some, it symbolized the end of New York City’s soul as we know it, the beginning of a corporate, stale, Disneyfied city. For others, it was a rebirth, a defiant reversal of a downward spiral that had unleashed crime and middle-class flight throughout the five boroughs. On February 11, 1981, when the 42nd Street Development Project announced its plan.

By 1981, Times Square had been a dicey part of town for quite awhile. Longacre Square (renamed for The New York Times when the paper erected a skyscraper there in 1904) had a hot theater and restaurant scene from the 1890s through the 1920s, but the area struggled through the Great Depression. By World War II the area was primarily a prostitution hangout for sailors on leave.

During the late 1970s, the Mayor Ed Koch and Governor Hugh Carey pushed through “moral reforms” to the area, such as changing the penal code to make soliciting prostitution a misdemeanor (it had previously been a violation), subjecting massage parlors to rigorous Department of Health codes and enacting a one year moratorium on new “adult physical culture establishments,” which included all kinds of fun activities. In 1973, the newly appointed Office of Midtown Planning and Development released a “Vice Map” of Times Square to help locate dens of immoral businesses. With these “clean up” efforts underway, the government approached businesses and hotels about investing in the area.

The first proposal with momentum, CA42, featured huge office buildings, shopping malls and a giant entertainment complex with a ferris wheel and ride through the sky emulating Disney’s Epcot Center. By 1980, however, Mayor Koch was convinced that the project was overly tacky, and confident the City could find different investors.

A year later, a city and state partnership came back with 42DP, a new plan that scrapped the theme park, revitalized several of the historic theaters, downsized some of the new giant buildings, and called for all private funding. The government’s contribution would be its use of eminent domain. Writer Phillip Lopate presciently predicted that the proposed plan imagined “a visual clutter so extreme that it makes the simple transversal of one city block as adventurous as passing through a gauntlet.” Lopate also asked whether the perceived problem with Times Square was its sexual mores or the people who frequented it, “who are the wrong class and color…I wonder if the city knows how lucky it is to have a raunchy street so famous and so densely compacted.”

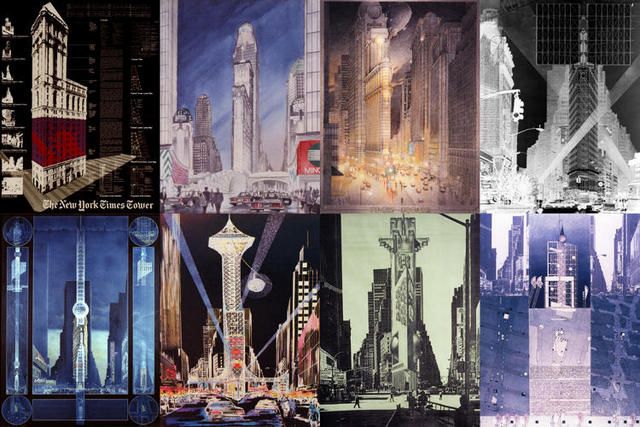

Submissions from the Municipal Art Society competition

Nothing comes easy in this town, even when the people behind an idea are the leaders of government and industry. Koch got the final legislative approvals for 42DP in 1984, but the wave of subsequent lawsuits from everyone from First Amendment porn groups to developers with losing bids lasted until 1990. During the early ’90s, the Municipal Art Society played a key role in urging the retrofitting of Times Square buildings, rather than demolishing them for bland office buildings.

The key architect employed for this stage of development, Robert Stern, had close ties to Disney, and in 1993 Mayor Dinkins’ administration welcomed Disney to Times Square after all, with the company taking over the New Amsterdam Theater to launch their first Broadway show, The Lion King. (The deal was actually executed a month into the Giuliani administration.

Changes in Times Square were far from over. The 1990s saw a continued exodus of porn shops, peeps shows and other “vice.” As new buildings went up and Mayor Giuliani trumpeted crackdowns on petty crime, people came to associate the 90s as the decade that transformed Times Square and made it one of the biggest tourism hotspots in the world. Less remembered is the 1981 plan that set it all on motion.

Read more from Today in NYC History on Untapped Cities and on janos.nyc

Subscribe to our newsletter