Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Richard Roth Jr., one of the grandsons of esteemed architect Emery Roth, was a fresh new architect right out of school when Project X was set to begin. It was slated to be a high-profile tower directly behind Grand Central Terminal that would revolutionize the architecture along Park Avenue and in the city as a whole. The project, which would become the Pan Am Building (now MetLife Building), would bring together two leading figures in modern architecture: Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi. It was Roth’s job, though, to make sure it all came together.

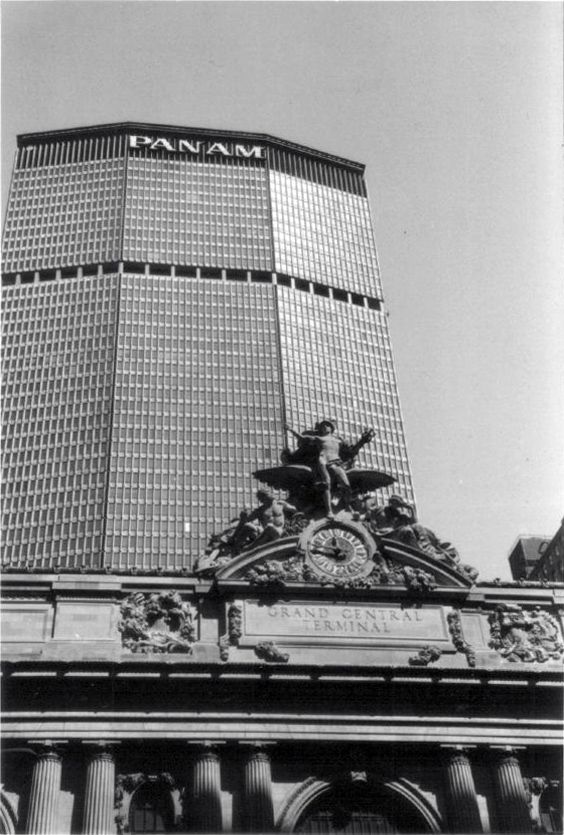

The Pan Am Building, now known as the MetLife Building, was at the time one of the city’s most controversial buildings due to its position and style. But today, many preservationists are working to maintain and protect the building. To celebrate the building’s 60th anniversary this week, we’re uncovering 10 secrets of the Pan Am Building, tracing back to the first proposals up to today.

The legacy of the MetLife Building, as well as its monumental construction, was discussed by Roth himself in a talk moderated by Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers. You can watch the talk, along with a series of other exclusive interviews with the late Richard Roth Jr. in our on-demand video archive. The archive has over 300 past virtual experiences you can watch whenever you want. Become a member at the Fan tier or higher to unlock the archives!

The Pan Am Building once had a helicopter deck on its roof, situated at 808 feet high. After a contentious approval process, helicopter service began in December 1965, and trial runs for the roof began with a Chinook helicopter. The service was operated by New York Airways, which flew Vertol 107 helicopters from the helipad to the Pan Am terminal at JFK International Airport. The idea of a multi-modal, multi-level city was first popularized in 1908 by Moses King, and just 60 years later that dream came to fruition. In 1966, the architectural historian Reyner Banham wrote in The Architects’ Journal: ”There is no other way to come into the island city of Manhattan. From now on, it has to be a helicopter or nothing.”

The concrete helipad was in operation from 1965 to 1968. The Vertol 107s helicopters also serviced Teterboro Airport for a period of time. However, few people were in demand of the service, so the helipad shut down just three years later in 1968. The helipad reopened in early 1977 with flights aboard Sikorsky S-61 helicopters, but the service was shut down just three months later due to a deadly accident. On May 16th, 1977, a rotor blade broke off a helicopter after the landing gear failed on the front and the helicopter toppled over. The blade fell down the side of a building and hit a window of the Pan Am Building on the 36th floor. From there, it split into two, with one part killing a pedestrian from the Bronx on Madison Avenue while she was waiting for the bus. More pieces of the rotor blades were found four blocks north of the building.

Walter Gropius was the founder and leader of the Bauhaus, a German art school located in Weimar that strove to unify mass production with creative artistry. Gropius gained fame for his designs of the Fagus Factory in Germany, the University of Baghdad, the Harvard Graduate Center and Boston’s John F. Kennedy Federal Office Building. One of Gropius’ only projects in New York was the Pan Am Building, which he co-designed with Pietro Belluschi; the latter designed Alice Tully Hall at the Juilliard School.

Alongside Richard Roth, whose own designs with his family’s firm include the World Trade Center, Gropius planned the building in the International style. According to the Getty Research Institute, internationalism is “characterized by an emphasis on volume over mass, the use of lightweight, mass-produced, industrial materials, rejection of all ornament and colour, repetitive modular forms, and the use of flat surfaces, typically alternating with areas of glass.” This is reflected in the building’s precast concrete exterior walls, glass windows, octagonal shape and repetitive forms.

In 1954, there were a few proposals to build a skyscraper above Grand Central Terminal as a way for rail lines using Grand Central to increase revenues. Erwin Wolfson proposed a 3-million-square-foot building to replace a five-story office building by the terminal. Using aluminum and glass, Emery Roth and Sons designed a 57-story tower that ran from north to south. The Roths worked with this orientation since the building’s shorter east-west axis matched the width of the tower of the nearby New York Central Building — now the Helmsley Building.

However, Wolfson brought in high-profile architects to reconsider the initial design, since he felt that the design was modest and underwhelming. These architects, Gropius and Belluschi, revised parts of the design and also reoriented the building so that it ran from east to west. Now, the MetLife Building blocks the view down Park Avenue.

In the 1950s, some architects planned skyscrapers that would have demolished the terminal altogether. While architects had envisioned that Grand Central would be the base of a massive skyscraper, two plans for the replacement of the terminal stood out. Fellheimer & Wagner designed a plan for a 55-story building that would have been the largest office building in the world. I.M. Pei, the architect behind the Louvre Pyramid and Roosevelt Field on Long Island, planned a futuristic 80-story, 5-million-square-foot tower that would have stripped the Empire State Building of its title of the world’s tallest building. Both proposals were poorly received, though, and neither was ultimately carried out.

To construct Pei’s tower, known as the Hyperboloid, the Terminal would have been knocked down, as Grand Central‘s profits declined considerably. Architectural Record stated that “its facade was crisscrossed by structural supports; overall the building resembled a bundle of sticks. At the base of Pei’s building, and again in its upper levels, the floors were left open and the structure was left exposed.” Although Pei’s design was not carried out and the Pan Am Building was constructed a few years later, Grand Central was under fire just a few years later. New York Central was planning to build a skyscraper surmounting the waiting room of Grand Central Terminal, and the following year, a more detailed plan by architect Marcel Breuer was put forward. Breuer had planned for a 55-story concrete building atop the terminal, turning the 42nd Street entrance into a lobby.

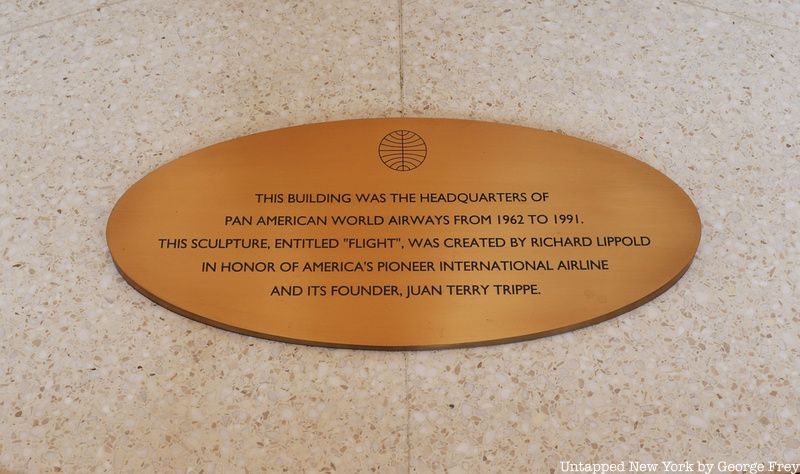

Pan American World Airways was the largest international air carrier of the U.S. for much of the 20th century. Founded in 1927 by two former U.S. Air Force majors, Pan Am pioneered jet aircraft and computerized reservation systems, and it even had a near-monopoly on many international routes. In 1970, for example, Pan Am flights went to 86 countries and carried 11 million passengers. Pan Am enjoyed great success while headquartered at the Park Avenue building. But after 15 years, the company considered moving away, and after facing huge financial losses during a recession in the early 1980s, the company put the building up for sale. Pan Am moved its headquarters to Miami and would close down just a few years later.

Some other early tenants in the building included Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Alcoa, Reader’s Digest, Chrysler, and the National Steel Corporation. MetLife, which took over the building in 1981, still has its head office and boardroom in the building.

In 1959, Roth, Gropius and Belluschi drafted a plan of a larger building with an “elongated” octagonal plan and bold pre-cast concrete facade. Robert A.M. Stern, David Fishman and Thomas Mellins observed that the design was actually based on “a well-known prototype, Le Corbusier’s unrealized skyscraper for Algiers (1938-42).” Le Corbusier’s first version of his plan for Algiers, developed between 1930 and 1933, represented his concept of a utopian Radiant City. He aimed to create a giant motorway in Algiers and tear down buildings to construct a new business district, a controversial move for the architect behind Villa Savoye. The unfinished Algiers skyscraper, along with his many other plans for the city, would have ushered in a new era of modern urban planning, but his unrealized notes were quite possibly picked up by Gropius and the team as inspiration for the groundbreaking building.

Stern, Fishman and Mellins also related the Pan Am Building to Gio Ponti and Pier Luigi Nervi’s innovative Pirelli Tower in Milan. The Pirelli Tower featured curtain wall façades and tapered sides, and it was one of the earliest skyscrapers to deviate from the typical block form. It was also the second-tallest building in Italy until 1995.

The MetLife Building originally displayed a 15-foot-tall “Pan Am” display and 25-foot-tall globe logos on its façades. However, the building was actually the last tall tower in the city built before laws restricted corporate logos and names from being displayed on top of buildings. Now, logos cannot be more than 25 feet above the curb and cannot occupy 200 or more square feet of the building.

But in 1992, the “Pan Am” display was swapped with neon “MetLife” displays a decade after MetLife moved into the building, and LED letters soon after replaced that display to conserve energy. So why were these changes fine? The sign replacements were permitted since the city government classified the new signs as an “uninterrupted continuation of a use” from before these new laws were passed.

The lobby of the MetLife Building was planned to include a number of art installations paying homage to the city. One of the most notable is Flight, a three-story wire sculpture by Richard Lippold containing an earthlike sphere, a seven-pointed star representing the seven continents and seas, and gold wires representing aircraft flight patterns. Composer John Cage even planned a musical program to complement Flight, but Lippold instead convinced management to play classical music in the lobby.

Manhattan, a 28-by-55-foot mosaic mural of red, white, and black panels by Josef Albers, was removed in a 2001 renovation but was replaced by a replica in 2019. Previous works that have since been removed include an architectural mural by György Kepes, suspended over the 45th Street entrance. The mural consisted of a set of aluminum screens with concentric squares and was removed in the 1980s.

Roth’s original plan for the 50-story building called for three theaters with a total capacity of 5,000, an open-air restaurant on the seventh floor and a 2,000-spot parking garage. While these plans did not come to fruition, some of the plans were adapted into the Sky Club, a private lunch club on the 56th floor. The Sky Club featured a private restaurant for members, who included the founder of Pan Am Juan Trippe. Trippe commissioned a mural made of clipper ships for the Sky Club. On the two floors above was the Copter Club for passengers of the helicopter service, although it only remained open for three or so years.

Upon completion, the Pan Am Building was one of the most hated buildings in the city. Ada Louise Huxtable, perhaps one of the most outspoken critics, called the building “a colossal collection of minimums”, with the lobby artwork being a “face-saving gimmick.” The Swedish-born American sculptor Claes Oldenburg mocked the building’s placement through his artwork Proposed Colossal Monument for Park Avenue, NYC: Good Humor Bar. James T. Burns Jr. also wrote that the building’s placement was “occasionally inexcusably jarring,” while the lobby was something of a monolith.

Even after the lobby received a major renovation in the 1980s, the new decorations created “a space that is so forced in its joy, so false and so disingenuous, that they make one yearn for some good old-fashioned coldness,” according to Paul Goldberger of The New York Times. Over time, though, the criticism seemed to wind down, since many preservationists have advocated for maintaining the robust skyscraper and keeping most of its original features.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Helmsley Building at 230 Park Avenue!

Subscribe to our newsletter