100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

Image from New-York Historical Society

For over 200 years, the New-York Historical Society has served as a “steward of the city’s memory,” as described by the museum’s Associate Curator of Material Culture, Mike Thornton. Founded in 1804, the New-York Historical Society contains priceless artifacts that tell the story of not only New York City, but also the entire state and country as a whole, from the 18th century through the present-day. The Historical Society’s extensive permanent collection contains everything from monumental artworks, like Thomas Cole’s The Course of Empire series and John James Audubon’s “The Birds of America,” to mundane relics of everyday life in New York like a garbage can and a parking meter.

Bearing witness to and collecting momentos from more than two centuries of the nation’s history, the New-York Historical Society has countless fascinating tales to tell and secrets to uncover. From the Historical Society’s ties to Santa Claus to the contents of the oldest time capsule, here are the top ten secrets of the New-York Historical Society!

If you are an Untapped Cities Insider, you can join us for two special guided tours of the museum’s exhibitions. The first tour will walk us through the latest exhibit to open at the museum, Stonewall 50, and the second will explore the Historical Society’s permanent collections! Not an Insider yet? Become a member today to gain access to free behind-the-scenes tours and special events all year long! Learn more about our first visit, coming up on June 29th, here!

Before the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Natural History Museum and other museum institutions of the city we know and love today were established, there was the New-York Historical Society. The New-York Historical Society was founded by eleven men in 1804, the same year Lewis and Clark set out on their expedition to explore the west. At that time, the historical society became New York’s first museum.

When the historical society was founded, America as a country was fairly new. The founders wanted to make sure that the history they were witnessing, and had witnessed through the American Revolution, would be accurately preserved for future generations. On a walkthrough of the museum with Mike Thornton, the Historical Society’s Associate curator of Material Culture, he described the items housed inside as “a collection of collections,” with many national treasures to boast. Today the museum has hundreds of thousands of artifacts dating as far back as as the 18th century. Key pieces of the permanent collection, which tell the story of New York from the its early days as a Dutch colony to the present, are stored in open storage for visitors to view. The other galleries are filled with artwork and rotating exhibitions.

Back in 1804, New York was typically written with a hyphen between the words New and York, so it only made sense that the Historical Society should adopt this punctuation in its name. The hyphen was used in newspapers and books and applied to other states as well, such as New-Jersey and New-Hampshire. In the mid-1800s, the hyphen began to fall out of use, though the New York Times was another hold out, keeping the hyphen in the paper’s masthead until the 1890s. As an homage to the time of its founding and its mission of preserving the state’s history, the Historical Society continues to keep the hyphen in its name.

The hyphen was an uncontroversial mark until 1945 when, according to a New York World-Telegram report, an angered councilman noticed the hyphen on a subway ad and brought his frustration to his peers. Chief Magistrate Henry H. Curran told the president of the City Council that the hyphen was “like a gremlin which sneaks around in the dark,” and called for its removal. The Council did try to pass a law barring the use of the hyphen in New-York, but librarians and curators of the Historical Society held their ground. One curator even remarked that they couldn’t change it now, it was after all chiseled into stone on the building. This incident took place amidst the tragedy of World War II and was largely viewed as nonsense. A group of musicians even wrote a song poking fun at the debate, called “The Hyphen-Song,” which they performed at a City Council meeting.

Today, the hyphen remains proudly part of the Historical Society’s name. The Society’s summer softball team is named “The Hyphens” and its library blog is called “The Hyphen.”

There are time capsules hidden in buildings, parks and museums throughout New York City, some with opening dates set thousands of years into the future. The oldest, unopened time capsule, that was recently opened, belonged to the New-York Historical Society. The time capsule was sealed over 100 years ago by the Lower Wall Street Business Men’s Association during a celebratory parade. The parade was in honor of the area’s historical significance in the tea and coffee trade and the Revolutionary War. The route started at Fraunces Tavern and ended at 91 Wall Street where the presentation and sealing of the times capsule, an ornate bronze box decorated with faux-rope handles and paw-shaped feet, took place. The box was hammered shut with bronze nails and a silver hammer by the ex-mayor of New York and former president of Columbia University, Seth Low, and entrusted to the president of the New-York Historical Society.

The box was supposed to be opened in 1974, but due to a cataloguing error, it went unnoticed until the 1990s. Since the box had already missed its due date by twenty years, the opening was further postponed until October 8th 2014, as a way to mark the 400th anniversary of the Dutch colonization of the New World. At the highly anticipated opening, the contents of the box were revealed to be various documents wrapped in brown paper and envelopes labeled with neat cursive handwriting. Among the documents were a copy of the New York Herald from May 15, 1914, a color copy of the 1914 Almanac, a photograph of the daughter of John Jay, and a letter extolling New York and the Merchants’ Coffee House as the true birthplace of the revolution. While instructions called for the items to be returned to the box and resealed for another 100 years, the Historical Society determined that the items would be more useful as artifacts to be examined.

The New-York Historical Society is home to 132 Tiffany lamps, the largest collection of Tiffany lamps in the world. Surprisingly, this collection was not pieced together over time, but given to the museum in one gift from a single collector, Dr. Egon Neustadt. Neustadt and his wife, Hildegard, purchased their first Tiffany lamp in 1935 from an antique store in Greenwich Village. Over the next fifty years, the Neustadts’ Tiffany collection grew to include leaded-glass windows, desk sets, and other items created by the Louis Comfort Tiffany studio. The lamps at the Historical Society make up about half of Dr. Neustadt’s collection.

While the eponymous men of the Tiffany studio are well known enough, the Historical Society’s exhibit calls attention to lesser known stories of the women who worked at the Tiffany studio, known as The Tiffany Glass Girls. In 1892, in response to a strike by the male-only Lead Glaziers and Glass Cutters Union, Louis C. Tiffany created the Women’s Glass Cutting Department and hired women to replace the men. The department was run by Clara Wolcott Driscoll who designed many Tiffany lampshades and mosaic bases as well as smaller objects produced by the studio.

More of Dr. Nuestadt’s collection can be seen at the Queens Museum and at The Nuestadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, a non-profit established by Dr. Nuestadt in 1969 to house, inside a warehouse in Long Island City, his extensive collection.

The Federal Hall National Memorial on Wall Street, a former custom house, marks the site where the country’s first capitol building once stood. The original structure built on the site in 1703 was New York’s City Hall. After America won the Revolution and New York City became the first capital of the new country, City Hall was turned into the nation’s first Federal Hall. In 1789, in front of a crowd of onlookers, atop the balcony of Federal Hall, George Washington took the oath of office.

When the City Hall was to be repurposed as the nation’s capital, the city hired French architect Pierre-Charles L’Enfant to renovate it and give it a more stately feel. His design incorporated neoclassical symbols and the ornate railing you see pictured above. The railing’s design contains thirteen arrows, each representing one of the thirteen original states. When Federal Hall was demolished in 1812, after the federal capital moved to Philadelphia, many of its architectural remnants were brought to the Historical Society. This railing actually made a stop first at the Administrative Building at Bellevue Hospital where it was used on a portico. It was removed from the hospital in 1883 and presented to the New-York Historical Society the following year. In addition to the railing, the Historical Society also houses much of the furniture left behind when the capital moved south. Pieces of the original structure, including a piece of stone from the balcony on which Washington stood, can also be found inside the Federal Hall National Memorial.

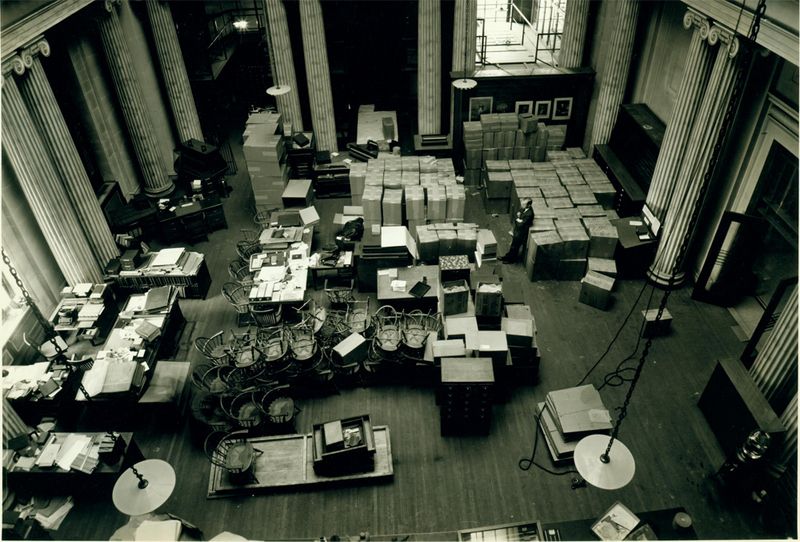

N-YHS Archives. Image via N-YHS

The Klingenstein Library in the New-York Historical Society is one of the oldest and distinguished in the United States, with more than 3 million books, pamphlets, maps, newspapers, broadsides, music sheets manuscripts, prints, photographs, and architectural drawings. Among these documents is one of the best collections of 18th century newspapers in the country, and a vast collection of Civil War materials, including Ulysses S. Grant‘s terms of surrender to Robert E. Lee.

Another distinguished title of this library is that it is one of only twenty libraries in the country qualified to be a member of the Independent Research Libraries Association. It continues to receive important research materials, and holds the archives to many organizations. In 2013, the library was a finalist for the National Medal for Museum and Library Service.

Inside the library you will also find one of the last remaining skylights inside the building. The galleries used to be lit by skylights from above. During World War II, these windows were covered, as were many large windows in New York City, and the curators were actually armed!

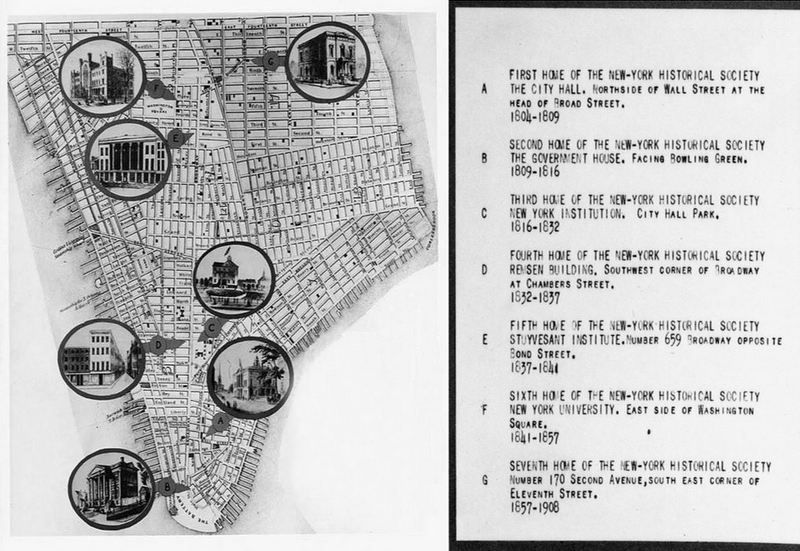

The 7 previous N-YHS locations. Image via N-YHS

The New-York Historical Society has only been in its current building on Central Park West since 1908. Before that it moved around quite a lot, changing locations seven times before construction began for 170 Central Park West in 1902. Its first home was at City Hall in Lower Manhattan until 1809. Next, it moved to Bowling Green to the Government House (no longer standing), which was originally constructed as the house of the President of the United States when New York was the temporary capital. The map above gives a nice visual of where the museum and library moved. The last before Central Park West was along Second Avenue on the southeast corner of 11th street.

The New-York Historical Society moved to the Upper West Side because of the amount of space available for its growing collection. Construction of 170 Central Park West broke ground the same year the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its doors on Fifth Avenue in 1902. You can see amazing photographs from the current location’s construction on the New-York Historical Society’s website here.

“Le Tricorne” tapestry on the left wall

“Le Tricorne” tapestry on the left wall

Pablo Picasso’s “Le Tricorne,” the largest work of art in the Historical Society’s collection and America’s largest Picasso painting, used to hang in the lobby of the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building. The 19-by-20 foot tapestry originally was used as a stage curtain for a 1919 production of the ballet “Le Tricorne” performed by the famed Ballets Russes company. The piece moved to the Four Seasons in 1957 and remained there for six decades. The interior of the famous restaurant was one of the rare interior landmarks of New York City, making ownership of the painting a controversial issue. While the owner of the restaurant wanted to remove the painting to make repairs to the wall behind it, preservationists feared moving the painting would destroy it.

The tapestry was successfully removed in 2015 and sent to an art conservation facility in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Later that same year, the piece was shipped to the New-York Historical Society and raised, inside a 23-foot long tube, by a crane through a second-floor window and into the gallery space. It took several hours for a crew to carefully unfurl the curtain. You can watch a video of the Picasso’s installation here.

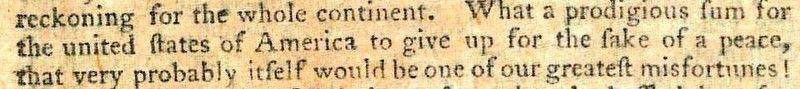

Above is what’s previously been though as the earliest use of “United States of America.” Image via N-YHS

The first usage of the phrase “United States of America” as the name of our country has long been disputed. Yes, it is in the Declaration of Independence, but there is some earlier evidence. The above image is thought to have been the first, appearing in the Virginia Gazette on April 6, 1776. This instance was discovered by Byron DeLear of the Christian Science Monitor. He bettered his own findings when he brought to the Historical Society’s attention a January 2, 1776 report by Stephen Moylan to George Washington. Moylan, an acting secretary to General Washington said “I should like vastly to go with full and ample powers from the United States of America to Spain.”

It may not seem so impressive now, but this was seven whole months and a week before the country declared independence from Britain. If Moylan came up with it, that is unclear. But there’s some idea that maybe his superior, George Washington had used it before, thus prompting Moylan to use it in a letter. We typically attribute the name to Thomas Jefferson, John Dickinson, Thomas Paine, and Elbridge Gerry. But now, Washington and Moylan can be added to the list of credit.

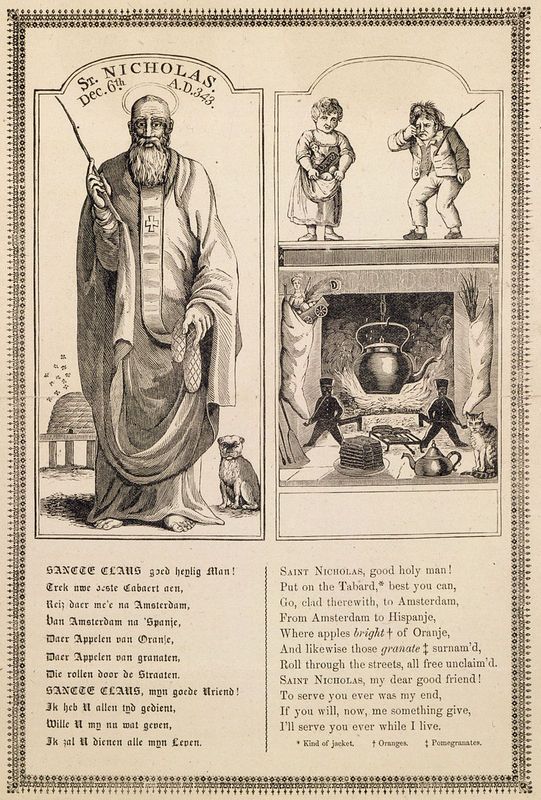

Alexander Anderson’s commissioned drawing of the American image of Santa Claus. Image via Wikipedia

John Pintard, one of the founders of the New-York Historical Society was a busy man who established lasting institutions and customs in New York and in the country. Besides serving on the executive board of many organizations like the New York Chamber of Commerce, Pintard was instrumental in advocating for the free public school system in New York today. He was also heavily involved in the plans for completing the Erie Canal, stayed in New York during the second cholera pandemic, and a deeply religious man.

That last part may not sound like a great accomplishment next to all the other things he’s done, but his religious involvement gave our country one of its most famous people: Santa Claus. St. Nicholas, the saint Santa is modeled after, has long been celebrated in Europe (and by the Dutch in New Amsterdam) around Christmas on a holiday called St. Nicholas Day. Pintard promoted St. Nicholas as the patron saint of both the Historical Society and New York. In January 1809, Washington Irving joined the Society and wrote a satirical fiction story called Knickerbocker’s History of New York where our American image of jolly, old Saint Nick the gift giving, chimney climber was created.

Starting on December 6, 1810, the Historical Society began celebrating St. Nicholas Day ever year. The same year, Pintard commissioned artists Alexander Anderson to create the American image of St. Nick, helping to popularize Santa Claus.

If you are an Untapped Cities Insider, you can join us for two special guided tours of the museum’s Stonewall 50 exhibition and the Historical Society’s permanent collections! Not an Insider yet? Become a member today to gain access to free behind-the-scenes tours and special events all year long!

Next, check out The 12 Oldest Museums in NYC and The Top 10 Secrets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

This article was written by Nicole Saraniero and Vera Penavic

Subscribe to our newsletter