Year in Review: Our Top Stories of 2024

From hidden remnants of old Penn Station to our favorite NYC book recs, discover which stories you read most last year!

Guastavino tiles, a famed, though now obsolete vaulting technique used in over 200 historical structures in the city, can give any New York City dweller or tourist a new appreciation for the artisanal origins found in architecture.

Like many of New York City’s cultural influencers, the family members who founded the eponymous Guastavino Company were immigrants. Rafael Guastavino, Sr. (1842-1908), born in Valencia, Spain, and trained as an architect with a Master Builder degree, brought his then nine year-old son Rafael Guastavino, Jr. (1872-1950), also Spanish-born, to the United States.

The “Tile Arch System” is one of 24 patents that the Guastavino father and son team devised over time while running the family business. The technique is used to create vaulted arches that consist of layered terra cotta tiles arranged in a zig-zag, most often, herringbone pattern and sealed with specialized cement. The structures that incorporate this architecture are also designed to be fireproof and incredibly stable.

Rafael Guastavino introduced a building staple, known to architects by name and recognized, at least by sight, to New Yorkers. Chances are that you have passed by, stood under or marveled at a historic archway or vaulted ceiling that embodies the tile arch system. These Guastavino tile locations in New York City will hopefully motivate you to take a moment in your commute or your stroll to appreciate the legacy to which New York City owes some of its most spellbinding architecture.

Photo by James and Karla Murray

In 2014, the Museum of the City of New York housed an exhibition on the work of the Guastavinos, named “Palaces for the People: Guastavino and the Art of Structural Tile.” The retrospective called attention to many structures, including the Ellis Island Registry Room (The Great Hall), which used to be the first step in the U.S. immigration process for people who were waiting to be inspected by Immigration Service Officers.

The room opened in 1900, and for over two decades, up to 5,000 immigrants passed through on a daily basis. Guastavino’s work, however, was not added until 1918. The Registry Room has since been restored to its appearance in 1918-24.

Located on the lower level of Grand Central Terminal, the Oyster Bar & Restaurant has been dishing out the freshest oysters and seafood dishes since 1913. Over a hundred years later, it remains a New York institution — famous not only for its seafood, but also for its adornment with Guastavino tiles. The tiles’ herringbone pattern takes center stage in this underground eatery, with lights running up and across the grand vaults.

After dining, patrons can step outside the restaurant and into the next Guastavino tile location. Warning: this one is a little “hush, hush!”

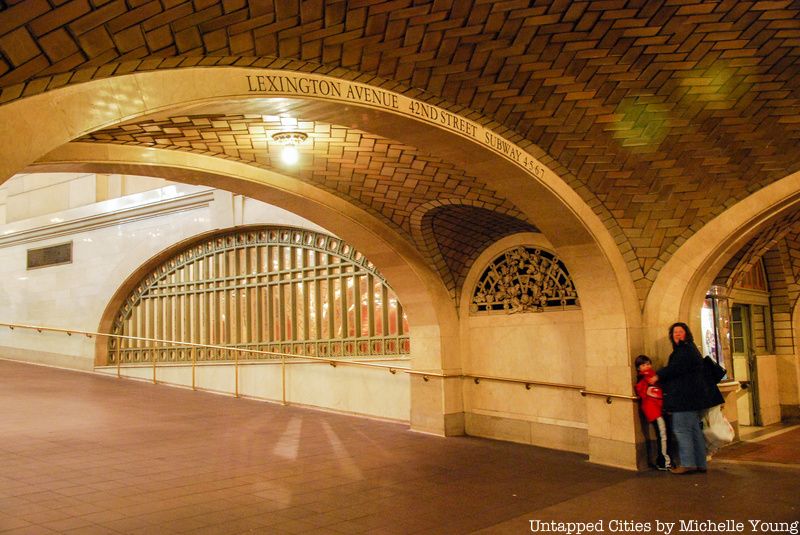

Got a secret to tell? The acoustic pockets of the Guastavino-tiled vaults in the Grand Central Terminal‘s Whispering Gallery act as the perfect pathway for messages. Just stand with a partner at opposite diagonals of the base and talk into the arches. Whispers will be heard across the distance as if you and your partner were standing right next to each other.

As we mention in our popular Secrets of Grand Central article, nobody knows whether this whispering gallery was built this way on purpose, but it has provided endless amusement for residents and tourists alike.

Sometimes the most surprising finds are in the most unassuming places, like a parking garage. On a visit to Grand Central Terminal, Untapped New York tour guide Justin Rivers noticed the famed arched herringbone pattern typical of Guastavino tile work. This area once part of The Biltmore Hotel, a grand Whitney Warren and Charles Wetmore-designed structure that was built as part of “Terminal City,” a compound of hotels and other buildings connected to Grand Central Terminal that was proposed in the original plans by Charles A. Reed and Allen H. Stem, along with William Wilgus.

One of the hotel’s best amenities was the ease with which guests could come and go using the hotel’s connection to Grand Central Terminal. Guests of the Biltmore arriving at Grand Central Terminal would have their luggage collected from the train by porters and then they would travel via tunnel to an elevator in the hotel’s basement and be carried up into the hotel without ever having to step outside.

The hotel was stripped down to its steel skeleton in the 1980s and all that is left of the original structure are small remnants like this passageway and its iconic golden clock, which can be found in the lobby of 335 Madison Avenue.

St. Paul’s Chapel, located on the Columbia University campus between Buell Hall and Avery Hall has Guastavino tiles on both the staircase and the dome. The staircase may have 2-3 layers of Guastavino tiles, whereas the dome may consist of as many as 5 or 6 layers of tiles. The tile work was commissioned as part of the master plan for the campus.

A recently completed renovation has restored the church to its original glory. And on your visit, fun fact: there’s a secret coffee shop hidden below St. Paul’s Chapel too.

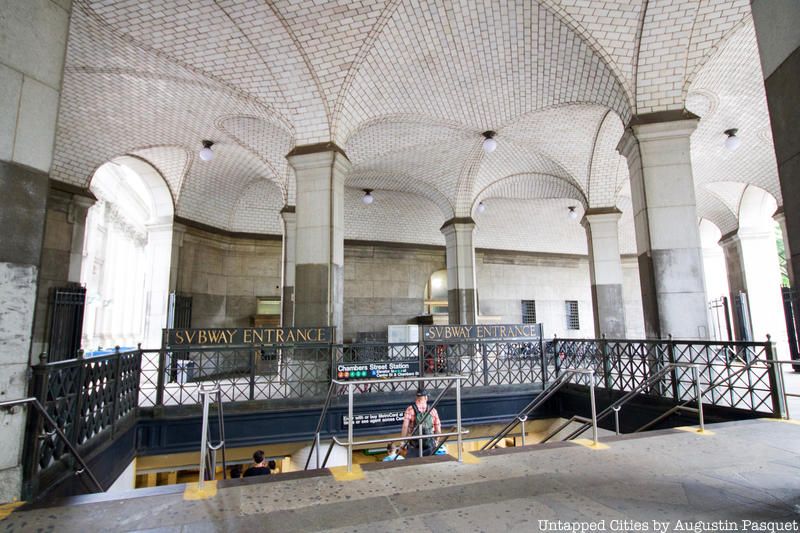

Don’t worry about conspicuously lingering about in this government building; there is no need to go inside to find Guastavino tiles. The south wing of the Municipal building on Chambers Street is fitted with a vaulted tile ceiling, though not in the characteristic herringbone pattern.

The Manhattan Municipal Building was the first to incorporate a subway station in its base, and it’s regarded as one of the most beautiful stations in the city, featuring 11 columns. According to MCNY, Guastavino “devised a series of elegant vaults to cover the space, adapting to its various shapes three basic forms: the barrel vault, used along the length of the colonnades; lunettes, curving between the columns; and groin vaults, to accommodate the diversely shaped polygons spanning the internal columns.” Also, check out 12 other secrets of the Manhattan Municipal building, including how you can access the cupola on the top.

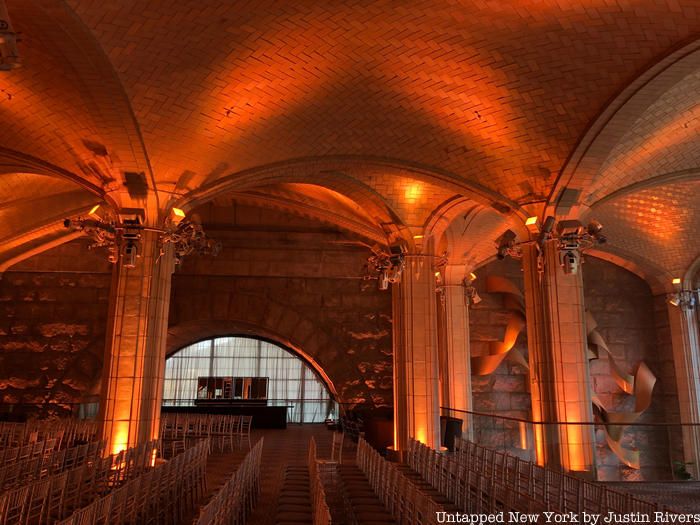

The event space, Guastavino’s (appropriately named after Rafael Sr. and Rafael Jr.), is one half of the Guastavino-tile vaulted space that sits beneath the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge. Many people use the space, which is designated as a New York City landmark, as a place to host weddings, parties and other gatherings. You might have also recognized it as a film location for Marvel shows like The Defenders.

The entire space used to be the Queensboro bridgemarket, filled with produce vendors year-round before the Great Depression. After an initial closure and re-opening in the late 1990’s, the space was converted into part Food Emporium, part event space. If you can’t get into Guastavino’s to see the tiling, there is a publicly accessible portion of the Queensboro Bridge, very much forgotten as a Department of Transportation storage area, that has more Guastavino tiling:

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is the world’s largest cathedral, but remains unfinished. In cross-shaped churches, a tower or a dome is constructed over the intersection of the four arms of the cross; a junction called the “crossing.” Guastavino tiles were used to build the dome that hovers over St. John the Divine cathedral’s crossing, the side aisles of the nave, as well as the staircases.

The Guastavino tile system lends major stability to the dome, also making it one of the largest free-standing domes in the world. It is now near impossible that the cathedral will ever be completed, as new apartment buildings have risen where the trancepts would have been built.

Image courtesy Prospect Park Alliance by Elizabeth Keegin-Colley

Image courtesy Prospect Park Alliance by Elizabeth Keegin-Colley

Prospect Park contains many structures built using Guastavino tiles, including the entrance shelters at Grand Army Plaza, the Willink Entrance Comfort Station, the tennis shelter, and the menagerie.

The Boathouse, in particular, features beautifully colored Guastavino tiles, which have shone brighter since the building was restored in 1999. The Beaux Arts landmark was built in 1905, and is now an Audubon Center, the first of its kind in the United States. Also, check out 12 other secrets about Prospect Park.

The entrance to the Bronx Zoo elephant house — now the Zoo Center — has two adjacent domes overhead. The domes are lined with the characteristic herringbone pattern of Guastavino tiles, which train your eyes to the vaulted ceiling of the one-story Beaux-Arts building, located in Astor Court.

Today, the space is home to monitors, Komodo dragons, and southern white rhinoceros, but make sure to look up and spend time studying the grandeur of the Guastavinos’ work.

Wolfgang’s Steakhouse (formerly the Della Robbia Bar) would have clearly been a stunning place to enter when it was built in 1913, but today it is even more remarkable for the fact that it is the “lone remnant of an interior ensemble destroyed in a 1960s modernization of the former Vanderbilt Hotel into a multi-use building,” write Gura and Wood in Interior Landmarks: Treasures of New York. The Vanderbilt Hotel was part of a larger grand plan around Grand Central Terminal, known as Terminal City.

Wolfgang’s is also an example of preservation and landmarking by means of community, grass-roots efforts. In this case, the organization Friends of Terra Cotta campaigned for its designation. In addition to the tiling work, the restaurant interior features polychrome ornamental tile by the Rookwood Pottery Company of Cincinnati.

A few steps after getting off the Roosevelt Island tram, you will be greeted by a stately but tiny welcome center. The welcome center structure dates to around 1909 when the Queensboro Bridge once had a trolley line, but this building was only moved here in 2007. There were five trolley kiosks, located between the inbound and outbound lower level roads between 59th and 60th Street. Like other parts of the Queensboro Bridge, the visitors center is one of the places in New York City you can find Guastavino tiling.

The last trolley ran on this line in 1957 and three of the five kiosks were demolished. One was moved to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Crown Heights where it functioned as the entrance to the museum until the museum was completely redesigned. Judith Berdy, President of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society, spearheaded the efforts to get the kiosk moved to Roosevelt Island, where it was restored and reopened as a visitors center.

The Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Nolita is yet another location that features Guastavino tiles. The tiles, are located in the catacombs below ground, where many past archbishops and cardinals are buried. Pictured here is a crypt for the Eckert family, above which you can spot the green-hued Guastavino tiles. Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral is one of the two locations of catacombs in New York City, the other is located in Green-Wood Cemetery.

Also check out how sheep help manicure the grounds of old St. Pats!

When the New York City subway first opened, the now abandoned City Hall station was referred to as “an underground cathedral,” according to John Ochsendorf, head of the Guastavino Research Project at MIT and co-curator of the “Palaces for the People” exhibit. Speaking to Susan Stamberg of Morning Edition in 2013, Ochsendorf continues, “The public was afraid to go underground at that time and so these vaults and this beautiful decorative, colorful ceiling really helped people feel comfortable in a grand space below the city.”

With its stunning tile work and stained glass windows, the station was designed to be the crown jewel of the New York City subway system. The architecture remains as beautiful as ever, but the station has been closed since 1945 due to its curved platform, which was deemed too short for longer trains that were later used.

Guastavino’s work appears in the Alexander Hamilton Custom’s House (the American Museum fo American Indian portion) as a giant domed ceiling in the massive rotunda under which workers once sat at the large marble counter to collect tariffs. The skylight that is supported by the dome weighs 140 tons and there is no metal support structure. The ceiling is made entirely of plaster and tile using the famous Guastavino method.

Subscribe to our newsletter