100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

For more than a century, the story of Seneca Village had been largely forgotten. The pre-dominantly African American village was settled in what was a remote and rural area of Manhattan in between West 81st and 89th Streets in 1825. Over several decades, the community grew to a population of approximately 225 residents, fifty homes, three churches, a school. When planning began for Central Park, the City of New York acquired the land through eminent domain. Buildings were razed, residents were made to leave, and all traces of the Village seemed to be lost.

In recent decades, the history of this remarkable community has been brought back into the light by organizations like the Central Park Conservancy and the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History. If you are an Untapped New York Insider, you can join one of two members-only tours of the Seneca Village site in Central Park led by the Central Park Conservancy‘s Historian, Marie Warsh on February 11th or February 16th in celebration of Black History Month.

Not an Insider yet? Become a member today to gain access to free behind-the-scenes tours and special events all year long:

Image courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

Image courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

Seneca Village was a unique community in many ways. Along with African American residents, there were also Irish and German immigrants living there. Unlike the shantytowns found in near what would become the southern end of Central Park, Seneca Village was a middle-class town where residents could build safe and stable lives. One of the most significant characteristics of the village was that it was the largest known concentration of African American property owners at the time. Owning a home in mid-19th century New York brought with it rights that many other African Americans didn’t have, mostly importantly, the right to vote.

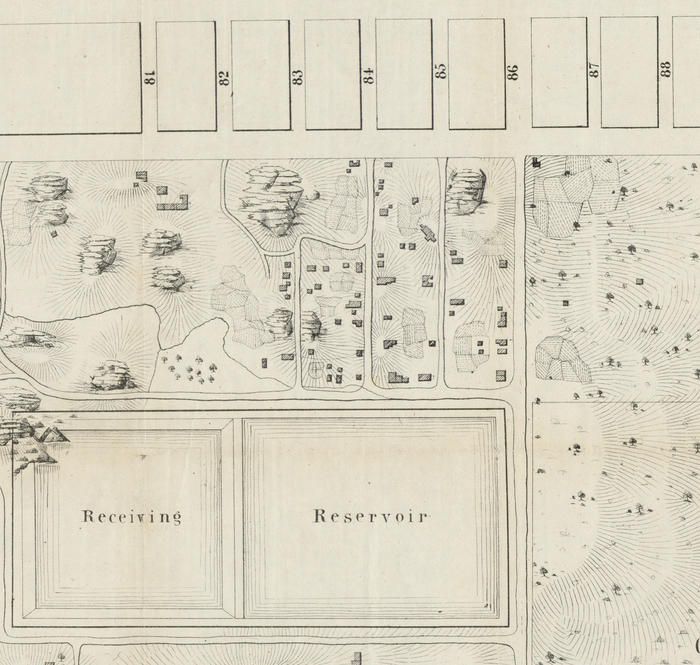

Egbert Viele, detail of Map of the lands included in the Central Park, 1856. Courtesy of NYC Municipal Archives.

The Seneca Village community flourished from 1825 through 1857, at which point residents had to leave. In 1853, the City of New York acquired the land by eminent domain. The City made use of eminent domain law, which allows the City to acquire private land for public use, to build Manhattan’s street grid. The residents of Seneca Village were compensated for their land, but many argued that the compensation was insufficient. Research is underway to determine where residents relocated to and where their descendants are now.

Image courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

Though the building of Central Park seemed to virtually erase the story of Seneca Village, scholars and archeologists in recent decades have been working to learn more about this historic community. In 2011, the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History conducted an archaeological excavation at the site that uncovered stone foundation walls and thousands of artifacts from residents that offer valuable clues to better understanding life in Seneca Village. Several different artifacts, including household items like an iron tea kettle, a roasting pan, and a stoneware beer bottle were found.

Summit Rock, the highest point in Central Park and an original feature in the Seneca Village landscape. Image courtesy of Central Park Conservancy.

Summit Rock, the highest point in Central Park and an original feature in the Seneca Village landscape. Image courtesy of Central Park Conservancy.

In October of 2019, the Central Park Conservancy launched an outdoor exhibit of interpretive signs throughout the Seneca Village site that mark the locations of historic features such as the Village’s churches, individual houses, and natural features, as well as provide more general information about the village. In honor of Black History Month, all Seneca Village tours are free during them month of February.

If you are an Untapped New York Insider, you can join us for one of two members-only tours led by the Central Park Conservancy‘s Historian Marie Warsh on February 11th and February 16th at 2:00PM.

Subscribe to our newsletter