Lijiang. The ancient city’s cobblestone streets stretch back 800 years.

Lijiang. The ancient city’s cobblestone streets stretch back 800 years.

I wake to the distant crowing of a dutiful rooster. Fumbling for my watch, I manage to find the one button that matters in the darkness. The usually benign glow of the Indiglo light attacks my unadjusted eyes. 6am. Time to get up. Stepping outside, I’m greeted by the crisp, cool mountain air. It’s still dark, but a tall silhouette approaches and greets me. Speaking in hushed tones, she leads me down a small winding pathway, past the creaking reeds to the shores of the magnificent Lake Lugu. She quickly climbs into one of the many ancient-looking wooden boats dotting the shore, and begins untying the ropes. In the distance, the rooster continues to call. The mysterious woman is a 58-year-old matriarch belonging to the Moso, an ethnic minority located in this particularly mountainous region in the Yunnan Plateau of China.

Early morning. A driftwood boat sitting on the calm shores of Lake Lugu.

Early morning. A driftwood boat sitting on the calm shores of Lake Lugu.

For the past month, I have been living with her family in a tiny village located in a tiny inlet of the lake. I call her “Ama,” which in her native tongue means “mother,” but is also used as a term of endearment and respect towards the older matriarchs. This morning, I’m helping her row out to one of the many scattered islands located in the center of Lake Lugu, in order to catch the sunrise.

Sunrise on Lake Lugu.

Sunrise on Lake Lugu.

Tucked in the southwestern-most corner of China, the province of Yunnan borders Tibet to the north, and Myanmar, Vietnam and Laos to the south. This relative isolation from the rest of China has allowed Yunnan to develop outside of mainstream Chinese thought and politics for an extended time, leading to a province far different from the rest of China. During the dynastic periods, Yunnan was known as a “land of barbarians”-an untameable place far outside imperial jurisdiction. Banished government officials, criminals, and soldiers were exiled here with little hope of ever reaching civilization again. Known by many names and home of many kingdoms since ancient times, Yunnan was so far removed from the rest of imperial China that Han scholars dubbed it the land “Beyond Mount Yun” in 109 A.D., but the interpretation “Land Beyond the Southern Clouds,” or ” Yunnan” (云å—), stuck, and it has been called that ever since.

Ama, one of the matriarchs of Lige Village in Lake Lugu, and my personal guide into the world of the Moso.

Ama, one of the matriarchs of Lige Village in Lake Lugu, and my personal guide into the world of the Moso.

For the past ten years, policies promoting economic development and tourism have increased in western China, and as a result Yunnan’s star is fast rising. It is routinely rated by Chinese citizens as one of the most livable provinces in the nation, and certainly one of its most unique travel hotspots. The headwaters for the Mekong and Yangtze River create flourishing ecosystems that vary from tropical rainforests, to lush highland plains, to jagged snow-capped mountain ranges. Yunnan’s relative isolation from the rest of the country has given it legendary folk status throughout China as a place of untamed beauty. It is also home to nearly half of the 56 officially recognized ethnic minorities in China, each with languages, histories, and cultures that differ significantly from the majority population of Han Chinese. Yunnan’s ethnic minorities, specifically the matriarchal Moso people of Lugu Lake, is the reason I’ve come this far. I’m here to make a documentary introducing their unique culture, which is at a crossroads now that economic development has finally reached their isolated location.

Rice fields just outside of Lijiang, on the way to Lake Lugu.

Rice fields just outside of Lijiang, on the way to Lake Lugu.

In order to reach Lake Lugu, I took a plane from Kunming, the fair-weathered capital of Yunnan, to Lijiang. The most well-known tourist gateway city to the countryside, Lijiang is home to a well-preserved ancient town complete with flowing waterways and picturesque bridges. This Old Town, as it is known as by the local Naxi ethnic group, is a UNESCO Heritage site, with a history dating back nearly 800 years. Once an important trade outpost along the Tea Horse Road (Yunnan’s closest equivalent to the Silk Road), Lijiang earned its namesake from the Naxi traders and their pack horses that rounded out harrowing mountain passes in order to transport temperamental teas–the kind that only grow in certain hard-to-reach places–to the rest of China. Think of it as an ancient version of “Deadliest Catch,” China-style. On any given afternoon in Lijiang, you will find groups of boisterous tourists walking along the brightly lit waterways and alleys of the old town, passing endless rows of small shops selling everything from loom-made scarves to hand-forged silver jewelry and cured yak jerky.

Lijiang: a view of the small streets you may find yourself lost in.

Lijiang: a view of the small streets you may find yourself lost in.

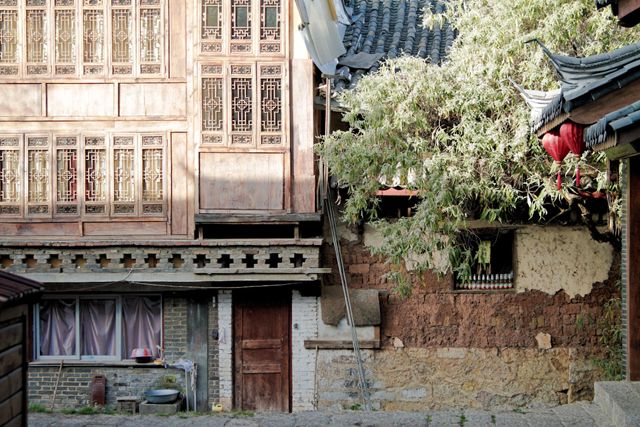

Like Venice or any other tourist-laden town, if one wants to escape the crowds, simply wander a little off the beaten path. Within five minutes of ambling along the ancient pebbled streets, you can find yourself in an unknown section of town, admiring the wondrous Naxi architecture as you stroll through river-lined neighborhoods and alleys that seem locked in a centuries-old time capsule. Elderly Naxi women pass by, sporting the traditional garb that their ancestors have worn for hundreds of years. The sun sets, and the red lanterns dotting the cobblestone paths are lit. Led only by the sound of trickling streams and the faraway bustle of the center of town, you find your way back into the fray of lights, people, and the overwhelming sensation of color and sound unique to evenings in Lijiang. As the gateway city for tourism in Yunnan, an itinerary to Lijiang is as unavoidable as the crowds that line it’s bustling Old Town, but the experience is memorable and worth a couple of days’ stopover.

Some Naxi minority people still live inside the ancient walls of Lijiang’s Old Town, but don’t let the shabby exteriors fool you. Many a Naxi household leads to large courtyards filled with cherry trees, small streams, and ornate interiors.

Some Naxi minority people still live inside the ancient walls of Lijiang’s Old Town, but don’t let the shabby exteriors fool you. Many a Naxi household leads to large courtyards filled with cherry trees, small streams, and ornate interiors.

As comfortable Lijiang was, I still had one more stop on my itinerary, Lake Lugu. The trip from Lijiang to Lake Lugu took me roughly 200 kilometers deeper into the interior of the Yunnan Plateau, and to a place few western travelers know to explore. Since arriving at Lake Lugu, I have spent one month living with the Moso people, working on field research and preparation for filming. Largely matriarchal with no traditional institutions of marriage, the unique culture of the Moso is at a crossroads now that China’s trickle-down economic policies are slowly seeping into their sleepy villages, potentially transforming Lake Lugu and its surrounding areas into a tourist mecca. But for now, would-be tourists are still largely discouraged by the tortuous journey from Lijiang, a rickety six hour bus ride (previously eight before the roads were completed) through seemingly endless mountain ranges that threaten to wind, dip, and climb their way into the psyches of even the most seasoned travelers. Though road conditions have improved, several kilometers along the route still consist of gravel and dirt roads, and during the rainy season, rock and mudslides along the mountain passes are frequent, even expected.

Lige Village, Lake Lugu.

Lige Village, Lake Lugu.

Travelers brave enough to sit through this endurance test are rewarded by some of the most spectacular views rural China has to offer: the raging turquoise glacial waters of the Jinsha River (a major headwater of the Yangtze), rural mountain outposts occupied by ethnic Yi people, picturesque valleys filled with lush green terraced rice fields, and finally the pristine shores of Lake Lugu. There are several Moso villages along the lake; Da Luoshui and Lige Village are more tourist friendly, with hot water and Internet standard in their inns. Smaller villages tucked in between the larger tourist-friendly villages may or may not be accustomed to accommodating overnight tourists, but are friendly, and for a filmmaker like me, absolutely pivotal in terms of understanding the cultural roots of the Moso.

A view of Lake Lugu, near the Yunnan-Sichuan border.

A view of Lake Lugu, near the Yunnan-Sichuan border.

Throughout mainstream Chinese media, the Moso peoples’ matrilineal society’s ancient practices, most notably involving “walking marriages”–where Moso men and women engage in what is inaccurately perceived by Han Chinese as wild one-night stands–have been the object of intense interest and scrutiny. In reality, the Moso practice what can be considered as a unique form of serial monogamy dating back hundreds, if not thousands, of years before Victorian ideals of marriage and partnership changed the western world, and by extension, our very own personal conceptions of love. Due to this unique aspect of the Moso people, interest towards the Moso has grown, and tourism is becoming increasingly popular.

Still dressed in traditional garb, the older generation of Moso are the gatekeepers to their unique culture.

Still dressed in traditional garb, the older generation of Moso are the gatekeepers to their unique culture.

Though tourism threatens to bring in outside influences and to erode their culture, the Moso have been incredibly resilient and creative in adapting their culture to the changing cultural landscape. The Moso family that I have been living with in Lige village is a perfect example of this. Of Ama’s four grown children, all of them have walking marriages–but one of them has a walking marriage relationship with a French national, and resides in Paris. Her four year-old daughter speaks both perfect French and Moso. Her three other children live in the village; two have moved out, the youngest daughter remains with her in their traditional wooden house, which now boasts a refrigerator and a flat-screen television, as well as the traditional fire-pit and cured whole-pig, all in one room. As Ama tells me this, she points to her North Face vest, which is layered on top of her traditional clothing. Beaming with pride, she tells me her daughter bought it in France for her, and it helps her keeps her warm as she rows the traditional zhucaochuan boats on chilly mornings. She gives a hearty laugh as she slaps my knee. Even she sees the irony. The fire in the middle of the room crackles and pops as we savor the momentary silence. Then, I ask her, “Is it possible that I help you row tomorrow morning?”

“Be up at six, and meet me outside the courtyard.”

Ama’s household dog keeps watch in the early morning hours, as she sets off to the boats.

Ama’s household dog keeps watch in the early morning hours, as she sets off to the boats.

And so in the dark hours of the morning, we row to one of the scattered islands in the middle of the lake. The sky above has slowly transitioned from shades of velvet to a fiery orange. We finally reach the cliff-facing shore of the island, known by locals as “Camel Island” for its vague resemblance to the humped ungulates found nowhere in this area. We disembark, and begin climbing up one of the camel’s “humps.” A small rocky pathway leads up to the top of the cliff. Grabbing the stalks of small bushes to maintain my balance, I look back; Ama’s 58 years seem to be of no impediment as she nimbly climbs up, humming along the way. Finally, we come to a small clearing. At the top, a small white stupa greets us, along with an unobstructed 360 degree view of the lake. Strings of Lung Ta-style prayer flags flutter in the wind. The Moso people have their own unique system of beliefs that draw from Tibetan Buddhism and their own shamanistic religion, called Daba. As I sit down on the yellow earth and begin filming, Ama begins her ritual, burning pine needles inside the stupa as she recites her prayers aloud. The fragrant smell of pine smoke delicately wafts into the eastern sky, where I could see that the sun was rising out of the mountains.

With Ama on the lake.

Watch a teaser trailer for Ricky’s new film concerning the Moso, “Under One Roof”

[vimeo 40910211 w=500 h=281]

Get in touch with the author @RickyQi.