An Original Stone Eagle Comes Home to Penn Station in NYC

A 7,500-pound eagle sculpture from the top of the original 1910 Penn Station building has been returned after years in hiding!

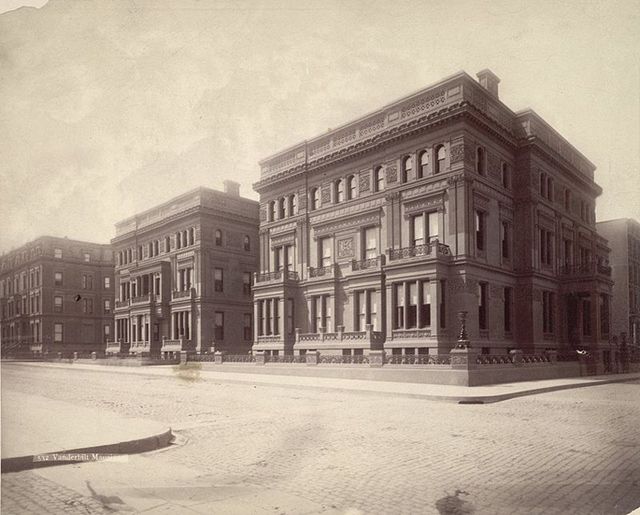

The William H. Vanderbilt House, commonly known as the Vanderbilt Triple Palace, was an elaborate mansion at 640 Fifth Avenue between 51st Street and 52nd Street. The mansion was perhaps the face of Millionaire’s Row along Fifth Avenue, along which a number of Vanderbilt and Astor homes were situated. Completed in 1882, the Midtown Manhattan mansion consisted of two portions, a single-family section in the south, and a two-family section up north, hence making it a “triple” palace. While William H. Vanderbilt lived in the single-family unit, two of his daughters, Emily Thorn Vanderbilt and Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard, occupied the two northern residences along with their families.

William Henry Vanderbilt was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt and the wealthiest American after taking over his father’s fortune in 1877, inheriting over $100 million. But his father frequently criticized him, notably calling him a “blockhead” and a delinquent. After a family trip to Europe on a steamship, though, the two became very close, giving William a greater role in the family’s enormous business. Perhaps his first business venture was becoming president of the Staten Island Railway in 1862 and later president of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. Vanderbilt’s investments were partly ruined after the firm Grant & Ward went bankrupt — Ulysses S. Grant actually convinced Vanderbilt to invest $150,000 in the firm, and Grant ultimately compensated Vanderbilt by mortgaging his Civil War memorabilia. Vanderbilt, who had nine children, was also a major philanthropist, donating extensively to the YMCA, the Metropolitan Opera, the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and Vanderbilt University.

Emily Thorn Vanderbilt was a major philanthropist as well, financing the creation of New York’s Sloane Hospital for Women in 1888. WIth her massive wealth, she and her husband commissioned Peabody and Stearns to build Elm Court, a massive mansion in the Berkshires that is currently for sale for $12.5 million. Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard also funded the YMCA alongside her father and was married to newspaper editor Elliott Fitch Shepard. She also owned Woodlea in Briarcliff Manor, which was designed by McKim, Mead & White. Margaret narrowly avoided being a victim of the RMS Titanic, canceling her trip for unknown reasons and deciding instead to take another ocean liner a week prior.

In January 1879, Vanderbilt bought a land lot on Fifth Avenue between 51st and 52nd Streets, purchased in part because he needed more space for his extensive art collection. Around that time, his sons Cornelius and William Kissam were respectively constructing the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House and the William K. Vanderbilt House just a few blocks north on Fifth Avenue. It took over 600 workers to construct the building, in addition to sixty European sculptors for facade and interior decorations. William Henry would visit the site daily and ensure that everything turned out perfect, and in under two years the home was completed. His home had such rare and fascinating collections of art that he invited visitors into the home on Thursdays, yet this quickly stopped after some close calls.

The Triple Palace was designed by John B. Snook and Charles B. Atwood. Snook was notable for his design of a number of notable cast-iron buildings, including many around SoHo and the original Grand Central Depot. Atwood was primarily known for his work in Chicago, designing a number of structures for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Herter Brothers, one of the first complete interior design firms, was hired to decorate the space.

The mansion had a brownstone facade and a courtyard and portico that separated the two sections. Both sections were connected at the first story, thus technically making the Triple Palace one structure, but the upper stories were disconnected. William Henry’s portion had 58 rooms and a central three-story art gallery with a large skylight, as well as an elaborate dining room, library, parlor, and drawing room on the first floor. The gallery had featured 207 oil paintings and watercolors from European artists. The drawing room was particularly notable for a ceiling mural by Pierre-Victor Galland, a French decorative painter. Emily’s and Margaret’s sections were notably less lavish but still had many similar features. With a facade of Connecticut brownstone, the mansion was designed in the Doric and Corinthian styles, with carvings of vines wrapping around all sides. Wrought-iron beams supporting the floors and roof. The home also featured ornate stained-glass windows designed by John La Farge, a rival of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

With such intricate and embellished features, William Henry enjoyed the comforts of the Triple Palace — for just four years. Vanderbilt suddenly passed away in 1885, and the home was transferred to his wife Maria. After Maria’s death, George was bequeathed the property, but he did not want to live in the mansion since it had become dilapidated. George was also working on constructing the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, but per his father’s will, he could not so easily sell the mansion. He developed the Marble Twins nearby in an attempt to slow development in the area, and he found an attractive opportunity to get the home off his shoulders with another wealthy New Yorker, Henry Clay Frick.

Frick was an industrialist and chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company who drew a lot of criticism for indirectly causing the Johnstown Flood. Frick, who wanted to put use extensive fortune to good use, reportedly said “That is all I shall ever want” on a drive past the Triple Palaces. Frick would rent out one of the palaces on a 10-year lease while George Vanderbilt was busy building the Biltmore Estate. However, he could not buy the house due to William H. Vanderbilt’s will, which barred George Vanderbilt from selling the home and art outside of the family. Via a loophole, though, the property and artwork were sold by Vanderbilt’s grandson to the Astors, who in turn sold the holdings in the 1940s. The artworks works sold for $323,195, and buyers included Paramount Pictures and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Unfortunately, demolition of the south section began in September 1947, and the house had been completely demolished by March 1949. The home’s destruction was not completely unexpected or frowned upon, since many believed that it had been an outdated remnant of the Gilded Age. It was later replaced by 640 and 650 Fifth Avenue.

Join us for our inaugural event for Archtober this year, a virtual talk on the Lost Mansions of Fifth AvenueL:

Next, check out the Vanderbilt Houses and Mansions in New York!

Subscribe to our newsletter