6 NYC Sites Connected to the Titanic Disaster of 1912

Uncover memorials and historic buildings in New York City tied to the tragic sinking of the Titanic.

Image via The Library of Congress

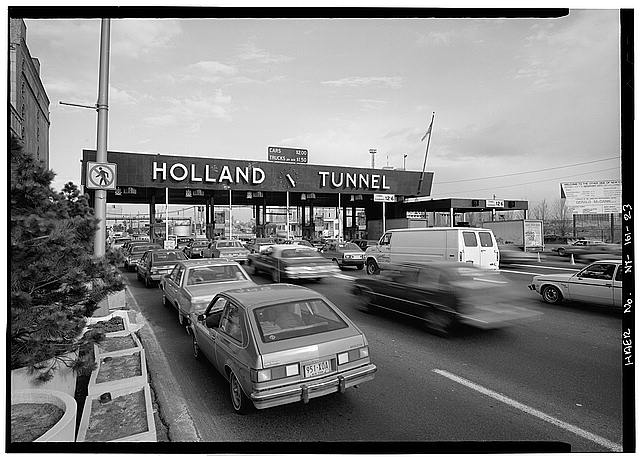

When New Yorkers think “Holland Tunnel”, they picture bumper-to-bumper traffic and expensive tolls. However, in the mid-20th century, the tunnel was not a fiasco of traffic and headaches. It was a remarkable feat of engineering complete with a revolutionary ventilation system, and completing the tunnel took a complex design plan and countless hours of hard labor.

New Jersey entrance. Image via The Library of Congress.

In 1913, seven years before construction commenced in 1920, the New York State Bridge and Tunnel Commission and the New Jersey Interstate Bridge and Tunnel Commission decided that constructing a tunnel was their only option to connect New Jersey to NYC. Building a bridge wasn’t feasible because New York’s elevation didn’t meet the 200-foot bridge height clearance for ships to use it. The dual coalition agreed on Clifford Holland’s twin-tube design and then in 1919, he was named chief engineer of the tunnel, and the tunnel was named for him.

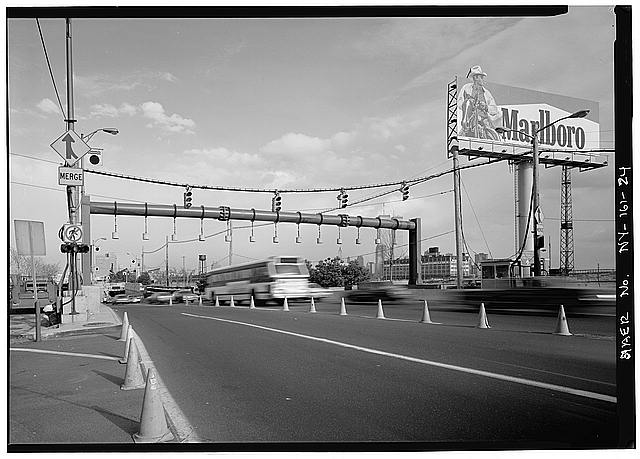

The height barrier. Image via The Library of Congress.

Underwater tunnels were not a new phenomenon but nobody knew how to construct them safely. In 1910, the first tunnel traversed the Hudson river but the vehicle exhaust would often make occupants, who were stuck in traffic in the tunnel, sick. With the intention to build a tunnel where occupants were not at risk for carbon monoxide poisoning, Holland recruited Ole Singstad, who went on to design the Lincoln, Queens-Midtown, and Brooklyn-Battery tunnels, as the head designer. As a team, they conducted tests on volunteers to determine the effects of fumes and found that four parts of poisonous gas per 10,000 parts of air could be deadly. All of their results led to the creation of a cutting-edge ventilation system.

Inside view. Image via The Library of Congress.

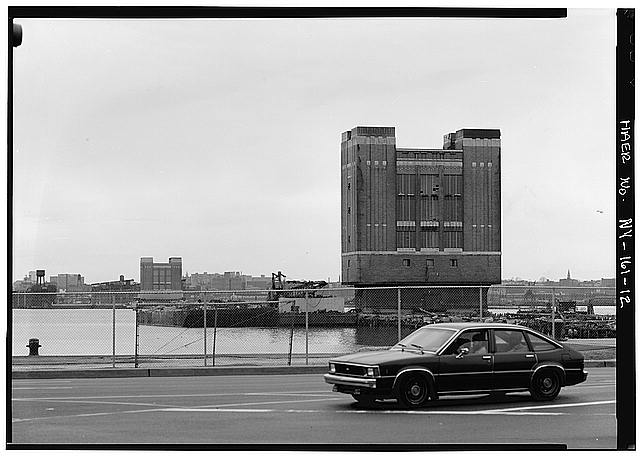

New York Land Ventilation Building (foreground) and New Jersey Land Ventilation Building (background). Image via The Library of Congress.

The two-duct system, later adopted by tunnels world-wide, utilized one duct to draw fresh air in and the other to pump out the exhaust air. Multiple ventilator fans and air shafts, in charge of circulating the air, assisted the two ducts in replacing the dirty air with clean air. In fact, there are 42 blowing fans and 42 exhaust fans but only 26 of each are in use because the others are for emergency purposes. In fact, the air in the 9,250 foot-long tunnel can be completely exchanged in a mere 90 seconds.

Blowers (3rd floor) in the New York Land Ventilation Building. Image via The Library of Congress.

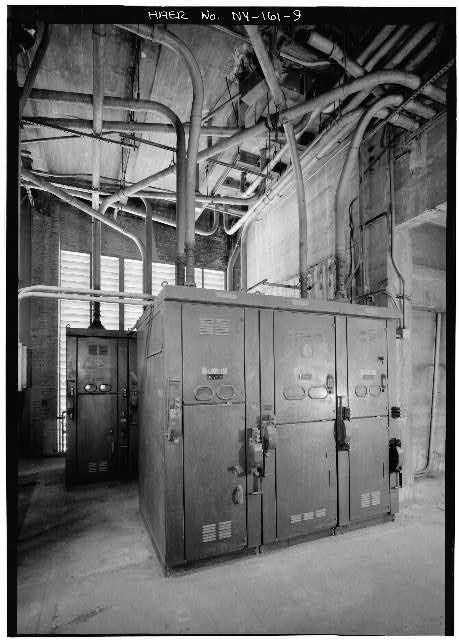

Main Feeder Station (4th floor) in the New York Ventilation Building. Image via The Library of Congress

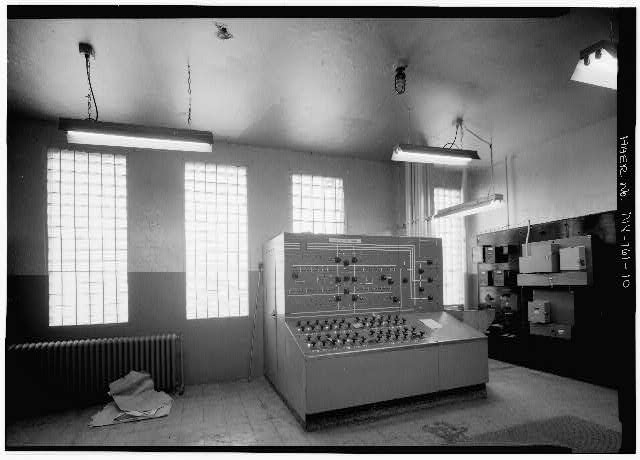

Distribution and Fan Control Panel (5th floor) in New York Ventilation Building. Image via The Library of Congress

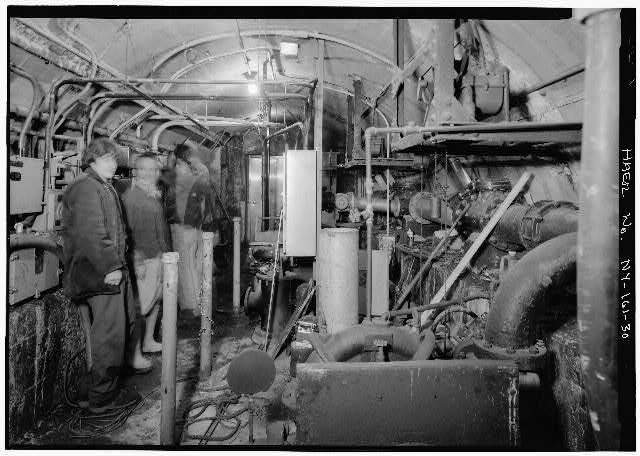

Middle pump room (located at the center and lowest point of tunnel) in North tunnel. Image via The Library of Congress.

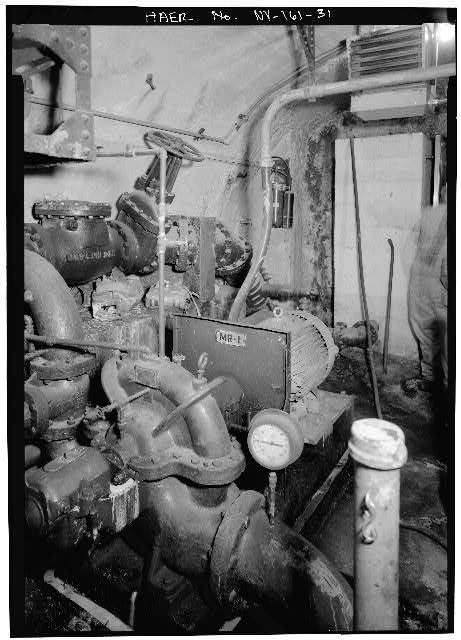

Pump in the middle pump room in North tunnel. Image via The Library of Congress.

The laborers, or “sandhogs,” as they were called, had a very physically taxing job. New York and New Jersey sandhog teams would follow a 240-ton hydraulically-powered shield removing mud, blasting through rock, and bolting a series of iron rings together which then formed the tunnel’s lining. In 1927, after seven years of construction, the “sandhogs” joined the two sides of the tunnel.

Headquarters and Maintenance Building. Image via The Library of Congress.

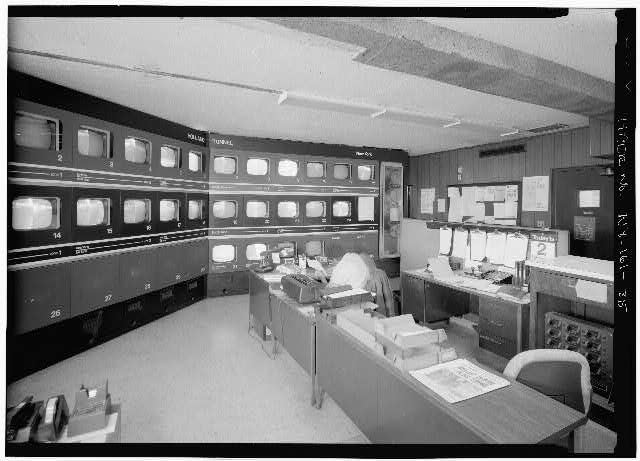

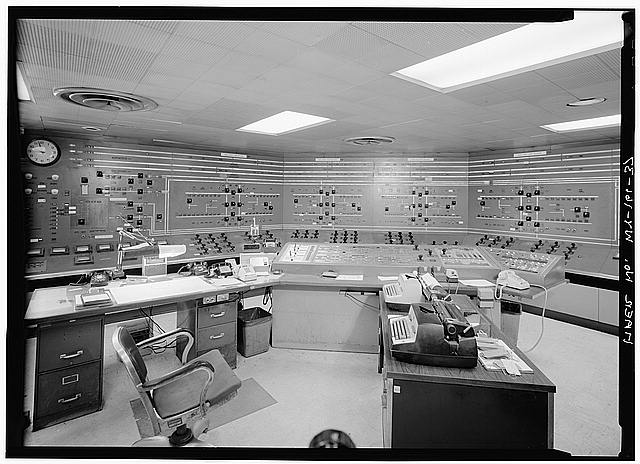

Traffic Monitoring Room in the Headquarters and Maintenace Building. Image via The Library of Congress.

Main Control Room Panels in the Headquarters and Maintenance Building. Image via The Library of Congress.

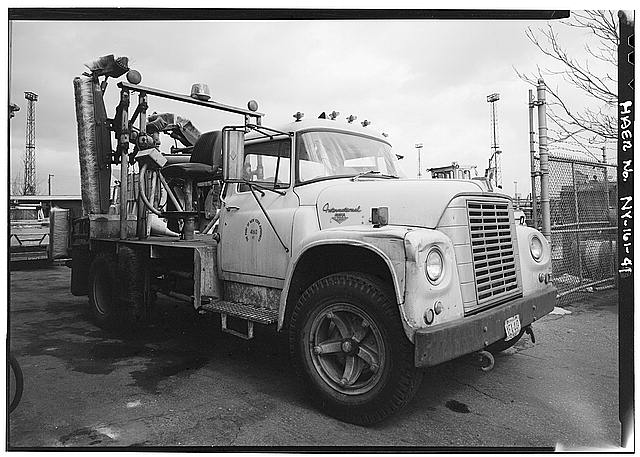

Tile Cleaning Truck. Image via The Library of Congress.

Back of Tile Cleaning Truck. Image via The Library of Congress.

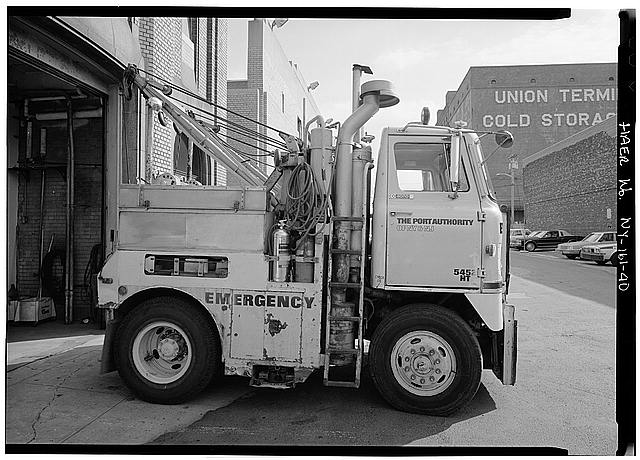

Emergency Truck. Image via The Library of Congress.

The first cars drove through the tunnel a few minutes after midnight on November 13, 1927, after former president Calvin Coolidge opened the tunnel that afternoon. Supposedly, the first vehicle to drive through the tunnel was a delivery truck headed to Bloomingdale’s in Manhattan. 52,000 other vehicles followed the delivery truck during the first twenty-four hours the tunnel was opened. Formerly known as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the Holland Tunnel was given the status of a National and Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil and Mechanical Engineers in 1984.

For more Untapped transportation, check out a Sneak Peak at the New Caltrava Transportation Hub and Hudson Yards, and for more Untapped tunnels, check out the Abandoned Atlantic Avenue Tunnel in Brooklyn.

Subscribe to our newsletter