6 NYC Sites Connected to the Titanic Disaster of 1912

Uncover memorials and historic buildings in New York City tied to the tragic sinking of the Titanic.

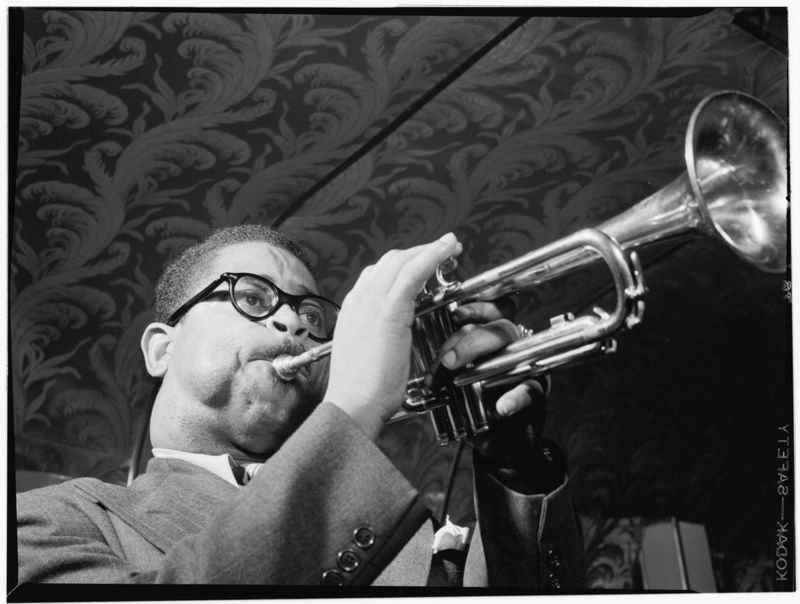

Image via Flickr courtesy of The Library of Congress

The Cotton Club might be Harlem’s most famous surviving jazz venue, but during the Harlem Renaissance that started after World War I and ended sometime during the Great Depression, it was also the neighborhood’s most notorious. It had been opened by Jack Johnson, the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion, as the Club Deluxe (or Club De Luxe) in 1920. White gangster and bootlegger Owney “The Killer” Madden bought and took over the club in 1923–the same year he was released on parole from what would have been a twenty year-long imprisonment at Sing Sing. He would use the venue, which he had renamed the Cotton Club, primarily as a means to sell bootlegged alcohol. The club was closed in 1925 for selling alcohol, but quickly re-opened. After prohibition, the club continued to feature some of America’s best jazz musicians, and attracted New York’s celebrities and socialites.

Although almost all of the performers and servers at the venue were black, Madden’s Cotton Club exclusively catered to white patrons; even the families of headlining black performers weren’t allowed in. Langston Hughes described the venue as “a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites,” and noted that white visitors to the neighborhood would flood “the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers–like amusing animals in a zoo.”

One major craze of the Jazz Age was exoticism, or Westerners’ romantic re-imagining of non-Westerners as being charmingly primitive and primal, and as such, the black dancers (who were only hired if they had light skin) were sometimes costumed to evoke exotic savages or animals, or dressed as plantation workers. The club did pay its performers extremely well, which could be the explanation for why so many talented black performers worked for the racist and anti-integrationist establishment.

The club kept up its exclusionary practices for seventeen years. Race riots caused the club’s Harlem location to close in 1936, but a new Cotton Club was opened quickly enough at Broadway and 48th Street. It’s current location on West 125th Street still caters to jazz lovers and swing dancers.

Image via The Library of Congress

See more from our Vintage Photography column

Subscribe to our newsletter