Artist-Led Tour of "ENCORE" Photo Exhibit w/ Mark S. Kornbluth

Join photographer Mark S. Kornbluth for a visual exploration of NYC's Broadway theaters at Cavalier Galleries!

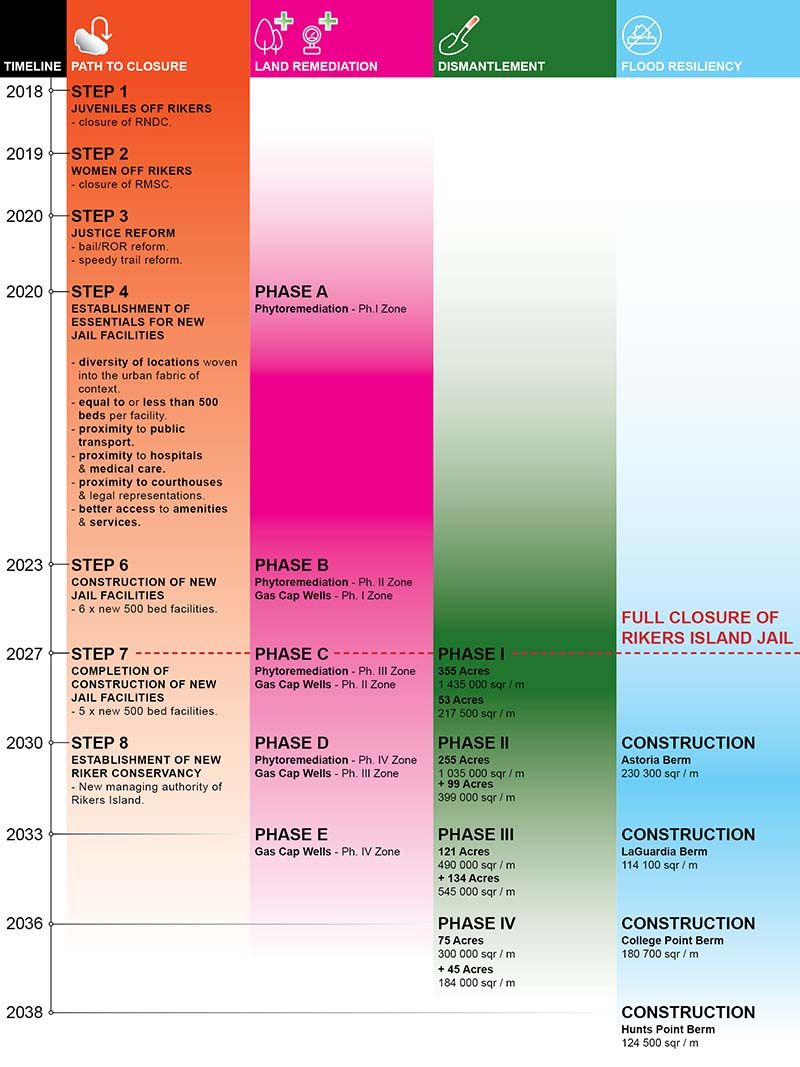

The recent announcement of the closing of the Rikers Island jail has already raised questions about the future potential of the land itself, with redevelopment already mentioned. But what if Rikers Island, of which 83% is actually landfill, could be returned to its original, natural state as a means of combatting climate change and sea level rise, while also environmentally remediating an already polluted island? Could the remediation of the island also support the process of closing the jail?

This is precisely what Swiss/Australian architect Mark-Henry Decrausaz hopes to achieve with his proposal, New Rikers, developed as part of a studio in the fall of 2016 at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, under the direction of Michelle Young, the founder of Untapped Cities who is a professor at the school.

The below text and visual images have been adapted from the website Decrausaz created as part of the class.

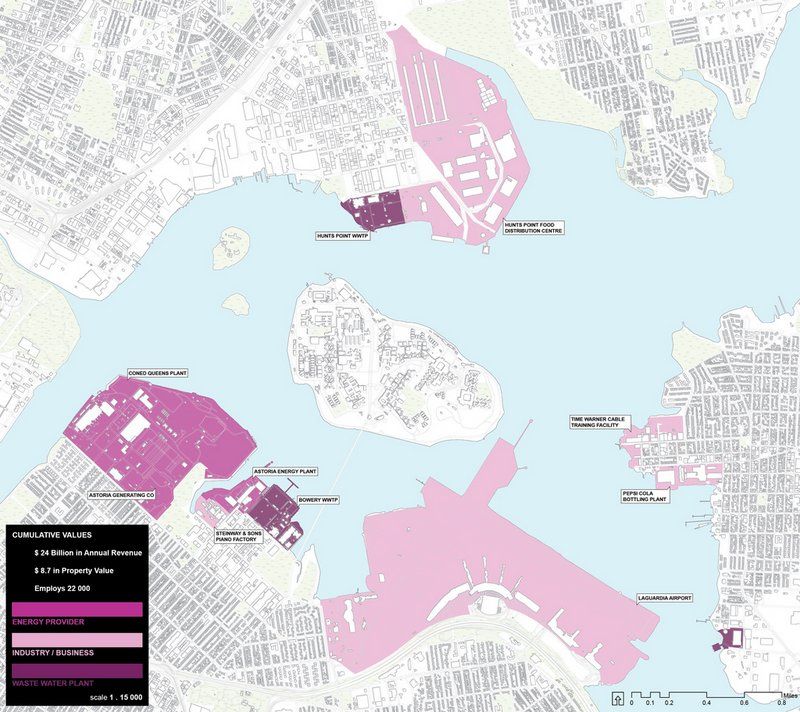

Could we envision Rikers Island as the location for new housing in New York? Perhaps Rikers Island could become a new home for industry, directly mirroring its immediate surroundings, serving clients such as the Hunts Point food distribution center, LaGuardia airport or the multiplus other local manufacturing and service businesses? What if the island were be transformed into an open space akin to Central Park or Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, a manicured pastoral green space for the local residents of the area and the population of the greater city?

Turning Rikers Island back to its original state

While all of these are possible, some are more probable than other, and some are preferable than the rest given the complex social, environment and urban conditions of Rikers Island.

This project serves to explore the question of a “New Rikers Island” and how to transform a troubled and increasingly problematic jail and underused territorial artifact in a design that can serve the local population and the city of New York while also addressing the issues around justice reform and how they intersect with architecture and urban design.

Localizing Rikers Island

To further delve in the urban conditions of Rikers Island also requires a understanding of its history. The island was not always as we know it today and was in fact originally less than a fourth of its current size. How it grew to its current proportions comes from a well established urban tradition of New York city; landfill.

Rikers Island was reclaimed land via barge fed landfill operations and grew to it current size over the span of six decades. At one of the first mappings of Rikers in 1885, the island was 68 acres, previously to this it was settled by Dutch farmers, used as a camp during the American Civil war and was finally sold to the city of New York in 1884.

In 1888, the New York Times published the article: “To Build a Bigger Island,” espousing the “scheme includes the reclamation of a great deal of land belonging to Rikers Island and bought with it.” In 1907, a second article about this same process and its virtues, combined with the growing garbage problems of the city, prompted city officials to expand landfill operations on Rikers Island

In 1924, all barge-fed operations were consolidated from Hart Island and Cromwell Creek in the Bronx to Rikers Island and by 1932, the island had already tripled in size to 262 acres. In the same year Rikers Island first began to function as a jail, where inmates were used as labour to reclaim land and process the barge trash into a usable landmass.

In 1935, the House of Detention for Men (Rikers Island Jail’s first name) was completed. For nearly a decade inmates worked the landfill into an artificial island until 1943 when barge fill operations were moved from Rikers Island to the Great Kills Marsh on Staten Island. This was due in part to the increasing role Rikers Island was playing as New York primary jail and the island’s inability to manage the exponential rate of garbage produced by the city of New York. By 1950, the Rikers Island jail was in full operation on an island the size of 413 acres.

Given the site’s history as a landfill, one of the foremost environmental challenges facing Rikers is the build-up and steady release of methane from the decomposing content beneath the soil of Rikers Island. The release of these pockets of gas can cause movement or shifting in the substrata of the ground, that in turn shears and damaged the structure of the jails buildings and has resulted in broken water mains and foundations.

The continuous methane leaks on Rikers island have been sited as a carcinogen in multiple class action lawsuits against the New York City Department of Corrections from former inmates and corrections officers alike. And has also been linked to an increased incidence of asthma amongst those on the island.

One of the most common complaints on the island from inmates, corrections officers and visitors alike is the foul smell emanating from not only the decomposing garbage beneath the ground but also from the surrounding area. The presence of three wastewater treatment plants and industries processing rubber and metals in the surrounding area also adds to this issue of odour.

Industrial assets around Rikers Island

The aforementioned context of Rikers Island is heavily dominated by various forms of industry, many of which expel considerable amounts pollutants and particulates into the air around Rikers. The lack of vegetation on the island and in the local industrial areas compound this problem as plumes of smoke are carried on the prevailing winds across Rikers without any kind of barriers or protection.

Alone, these issues maybe be more easily addressed in remediating the soil in the case of methane leaks or deeper, more rigid foundations to address ground movement or increased vegetal density to help offset the odour and local pollution.

This is without even mentioning that people currently work and reside on the island and are affected by these issues everyday.

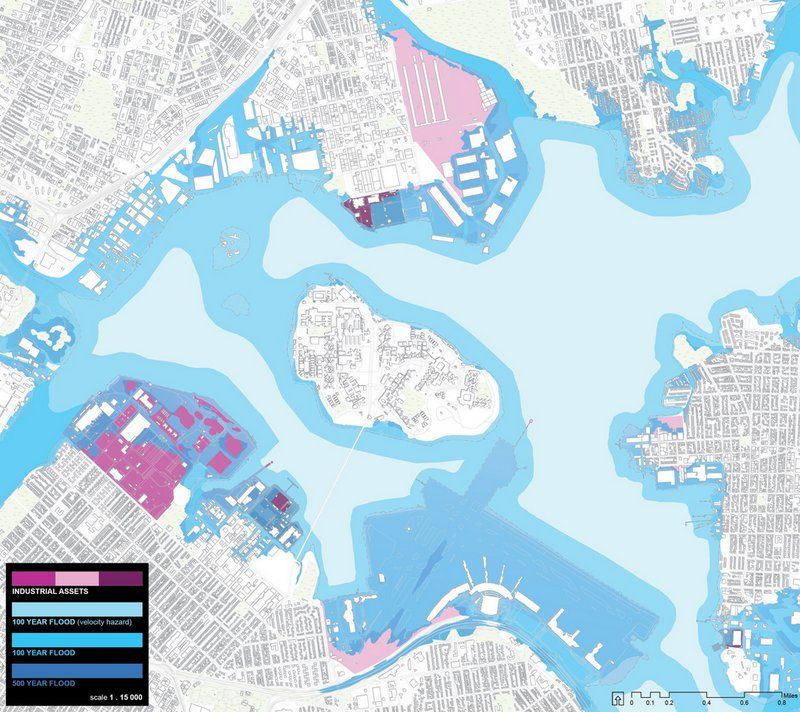

Flood map of Rikers Island and vicinity

Like many parts of New York city, the area around Rikers Island is dangerously susceptible to flooding, and as we saw in 2012 with Hurricane Sandy, such storms cause extensive damage to property levying a huge financial cost but also carry a devastating human cost.

Of great concern is the vulnerability of the previously mentioned industrial assets in the direct vicinity of Rikers Island. The implications of the flooding and subsequent shut down of these facilities are terrifying; no fresh water and potentially no power for days and after storm many may find their place of work closed as the important economic engines of the region go dark.

Given the likelihood of the increased frequency and severity of such super storms it stands to reason that action should be taken to provide flood resiliency to these key industrial assets and the area.

This proposal is founded around asking a fundamental design question: what is a possible future for Rikers Island that best serves relevant stakeholders, addresses the needs of New York and responds appropriately to its context?

As its core, the New Rikers proposal is project of geo-architecture, reshaping the island into a new urban form. With this idea comes the need to telegraph the necessary closure of the jail on the island, the establishment of a new administration or organization to manage the island in its new form and finding ways to effectively program the new urban space to make them relevant and useful to local stakeholders.

More simply put, through a multi-step process Rikers Island could cease to function as a jail, be progressively remediated and dismantled and then transformed into a network of flood resiliency projects with recreation programming to offer new green spaces to the underserved communities of Queens and the Bronx.

As we envision a future with a continued decline in the inmate population of New York, we can ask what happens to Rikers Island? Up until now it was politically expedient to put a vast majority of the inmate population in one place on Rikers Island. Bureaucratically it makes sense to silo much of the needed resources and facilities into one infrastructure. But the expediency and efficacy of this philosophy has been put into question in recent years and the recent announcement by Mayor De Blasio supporting the closure of Rikers Island represents an important political turning point.

As the population of inmates shrinks, more and more the island is presenting itself as a costly exercise in agglomeration. As the infrastructure of the jails suffers after years of neglect, little is done to address the island’s problems of connectivity and disrepair, this coupled with pressing environmental issues, continually raises the jail’s cost of operations.

Even without the proposition of closing the jail, or only assuming some populations will move off the island like the agreement to move juveniles in the Robert N. Davoren Centre to the Bronx, keeping Rikers Island as a jail always presents an out for the city government to move populations back to a troubled island given circumstance of perceived political or administrative necessity. This kind of bureaucratic yo-yo with jail locations has proven to be not only costly to the taxpayer but also harmful to inmates as it adds the uncertainty of jail incarceration.

This proposal is founded around asking a fundamental design question: what is a possible future for Rikers Island that best serves relevant stakeholders, addresses the needs of New York and responds appropriately to its context?

The dismantlement of Rikers Island

As its core, the New Rikers proposal is project of geo-architecture, reshaping the island into a new urban form. With this idea comes the need to telegraph the necessary closure of the jail on the island, the establishment of a new administration or organization to manage the island in its new form and finding ways to effectively program the new urban space to make them relevant and useful to local stakeholders.

More simply put, through a multi-step process Rikers Island could cease to function as a jail, be progressively remediated and dismantled and then transformed into a network of flood resiliency projects with recreation programming to offer new green spaces to the underserved communities of Queens and the Bronx.

Even assuming, and aspiring to, closure of the jail on Rikers, given the environmental conditions of the island, little reprogramming can be done without massive work on remediating the soil and preparing the substrata of earth for new structural foundations.

Other proposals to transform Rikers Island into residences or industry tend to ignore this key issue. Sadly it is perhaps easy for the general public to feel indifferent to the odours, carcinogenic methane leaks and structural instability of the built condition for inmates, but if Rikers were to become housing or a cultural centre, these issues would certainly outrage users and residents.

But what to do with the removed matter of a dismantled island? How does progressively remediating and excavating Rikers benefit the locals of Queens and the Bronx? And finally how does this address the issues of green space, flooding and lack of connectivity of the context?

The answer comes from finding a strategic reuse of the soil from Rikers Island and how it can offer a new kind of urban space and flood protection.

Flood protection in the form of green berms around Astoria, LaGuardia Airport, College Point & Hunts Point using remediated soil from Rikers Island

Flood protection in the form of green berms around Astoria, LaGuardia Airport, College Point & Hunts Point using remediated soil from Rikers Island

As explored previously, one of the pressing urban issues facing the context of Rikers Island is the poor state of preparedness in the case of severe flooding such as during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Part of the New Rikers proposal explores the potential of the strategic reuse of the subtracted matter from Rikers Island into berms for protection against floods. Adding berms to floodwalls can increase their effectiveness as the mass of material, in this case soil, can help absorb some of the inundation.

The berms were designed to protect the more heavily affected assets such as LaGuardia airports and the industries of Hunts Point, College Point and Astoria. These locations were also chosen due to their inaccessibility for the locals and workers of the region to the waterfront and how they could redefine the public relationship with the water’s edge condition.

The proposal utilizes two kinds of berms: the slope berm for the LaGuardia Airport berm and the park berm for the area of Astoria, College Point and Hunts Point. Both include a 15 foot flood wall to protect against 100-year and 500-year floods, and identify key pinch points to control and redirect flooding at moments where it is mitigated by the natural features of the land. Where they differ is in their ulterior functions.

The slope berm is shorter at 25 meters wide and inaccessible, but given the security requirements of airports it is unwise to too heavily program a berm on the exterior edge of runways. Nevertheless it provides much needed protection to a key transport infrastructure of New York and brings a powerful economic partner into the stakeholders of the project.

The park berm however is a far much social and accessible space at 50 meters wide offering plenty of room for programming and public thoroughfare or activation. As a long extruded park, it connected parts of Queens and the Bronx to the water along the edge of previously closed or inaccessible industrial areas. It is stepped in 10 meters wide sections to provide a maximum of usable terraced green space.

The berm provide something once lost to the residents, access to the water’s edge and a new green urban space to enjoy. The berms must then be made accessible to the general public by identifying and articulating key points of connection to public streets.This gives the berms the ability in subtly infiltrate the once closed industrial estates and creates a kind of porosity in the industrial landscape, liberating the path from commercial and transport centres to the waterfront of the Long Island sound.

See more information about the programming of the berms here.

Before any works can begin on remediation and dismantling Rikers island we must first address the presence of the inmates and working population on the island. This requires a roadmap for the closure of the Rikers Island jail and the identification of new or renovated facilities to absorb the inmates taken off the island. This idea has in fact already been explored by New York’s mayoral office and whilst it is costly and a long, drawn out process has been viewed as an ultimately cost-beneficial option given the decrease in jail populations and decreased cost of transportation and maintenance of the island.

The crux of this portion of the timeline requires the moving of groups of inmates off Rikers most logically in sequence of the future remediation and dismantlement phases of the island. This means that new facilities, ideally of 500 beds, should be built in an evenly distributed manner around New York city to allows better access to services and the families of representation of inmates.

Over time, as more and more of these facilities are completed and opening, portions of the Rikers population can be dispersed into these new jails until the final tipping point where full closure of Rikers can occur. Then work can begin in earnest to treat and remediate the island’s soil and transform it into the New Rikers proposal.

It is also at this point of closure that Rikers island can changes hands from its management by the Department of Corrections to a new conservancy board, managing the construction and future operations of New Rikers. This board could be composed of local stakeholders and representatives of the local key industrial assets to help convince these business to collaborate in not only the construction of flood resiliency for their buildings, but also new public amenities for the public of Queens and the Bronx.

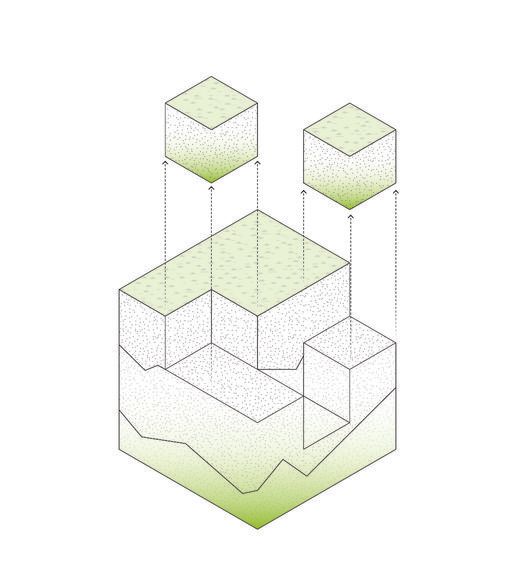

Sequencing of the land remediation on Rikers Island

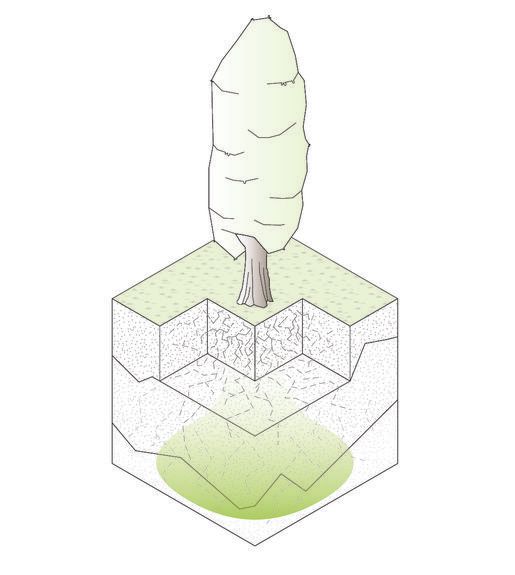

The remediation of the toxic soil conditions of Rikers Island makes use of two key techniques, Phytoremediation and Gas Cap wells, in progressive phasing based on the zones to be dismantled later.

Phytoremediation is a plant-based approach to land remediation that takes advantage of the ability of plants to concentrate elements and compounds from the environment. Some trees, most effectively Poplar stress, can absorb, trap and convert leaking gases like methane and convert it to oxygen.

This not only dramatically reduces the amount of gas leaking from the soil, but also can help improve the air quality of the site, a much need consideration for Rikers island given its industrial context with power plants and water water treatment plants in close vicinity.

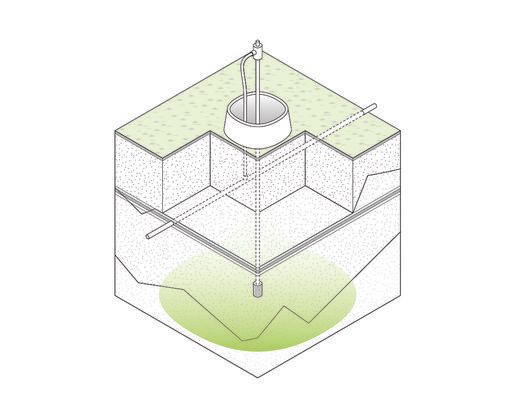

Gas Cap Wells are used to collect and redirect gases from brown sites or old landfills to mitigate the health implications and discomfort from actively decomposing substrata.

They do so by capping the ground plane with a bio-plastic sheet or membrane and the using suction wells to collect the subterranean gases and either store them and safely dispose of them at a later time or redirect the gas (most commonly methane) for industrial or energy production use.

The Land remediation of the soil matrix of Rikers Island is planned out in five steps in sequential order from phase A to phase E. First each zone is first populated with trees to undergo phytoremediation, which can then be used as stock vegetation for the future park berms, and is then capped and gridded with Gas Cap wells.

This sequence uses both Phytoremediation and Gas Cap wells in a staggered manner across the zones set for dismantlement to first help improve the air quality of the Island whilst inmates and workers are still present and then remove the excess gas with wells and collect it for later use in Rikers Island own power plant.

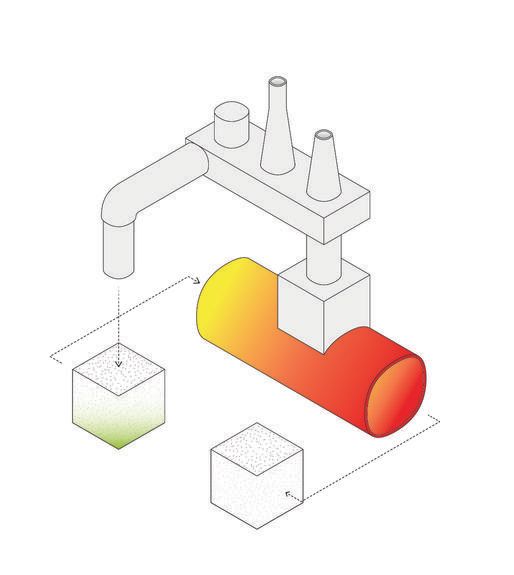

The next step is the eventual excavation and deconstruction of the island itself. This sequence is also broken down into four steps from phase I to phase IV where each phase removes a section, or zones, of the island. At each point the earth from the excavation of the island is treated by a process called thermal desorption to clean the soil, this is done in the converted powerplant on Rikers island, fuelled by the gas from the Gas Cap wells

To excavate an island presents a unique challenge working at the water edge, requiring specialized equipment such a barge excavators.

But in this challenge also lies a benefit, as soil can be directly loaded from excavation into barges for more easily transportation to the on-island treatment plant’s marine transfer station or elsewhere for storage.

Given the toxic, and potentially irradiated nature of the garbage under the surface of Rikers island, it is necessary to handle the soil with great care and ensure all workers are correctly protected while working this part of the timeline.

Thermal desorption is an environmental remediation technique that utilizes heat to increase the volatility of contaminants in soil such that they can be removed or separated from the solid matrix or matter (typically in the form of soil or sludge).

A thermal desorption system therefore has two major components; the desorber itself which heats and treats the soil, separating contaminants, and the offgas treatment system, which collects the separated gases and stores or retreats them.

These zones were derived from the sequence in which the island grew over time moving from the newest sections of the island inwards to the first region reclaimed using landfill. This creates a kind of symmetric return to the island’s original state and each zone beings to inform the amount of matter that can be use for berm construction, ultimately influence and size and proportions of the finished berms.

In conjunction with the phases of dismantlement, the berms are built within this same sequence with a slight delay for the treatment and processing of the soil for use in the berms construction. Here we see a more direct correlation between the disappearance of Rikers Island as we now know it and the appearance of that same earth as it functions as flood protection and new public space.

So how do these sequences of events ultimately line up? And what is the resulting timescale for the transformation of the Rikers Island jail into the New Rikers project?

A project of this scale is undoubtedly expensive and requires a huge amount of capital to see it finalized over its 20 year timeline. But it is also worth noting what this $5.1 billion sum of expense is ‘buying’ so to speak.

Firstly the New Rikers proposal addresses the need to reevaluate the urban conditions of inmates populations and finds better, more localized alternative for housing on Rikers Island. While costly in the short term, will deliver savings of up to $550 million a year after completion, effectively paying for the whole project within 10 years, before it is even completed. Secondly it provides much needed flood protection for the local industries, without which risk thousands of job losses and equal billions of loss in annual revenue and property value. Finally, New Rikers is also a gesture offering an underserved populace green space and waterfront access up until now denied to them.

When bundled together; justice reform, flood resiliency and new public space combined allows the project to make a persuasive argument for its own cost, and while it may appear utopian, the New Rikers proposal aims to answer that fundamental design question we originally asked:

What is a possible future for Rikers Island that best serves relevant stakeholders, addresses the needs of New York and responds appropriately to its context.

Discover more on the New Rikers website.

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Rikers Island.

Subscribe to our newsletter