Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

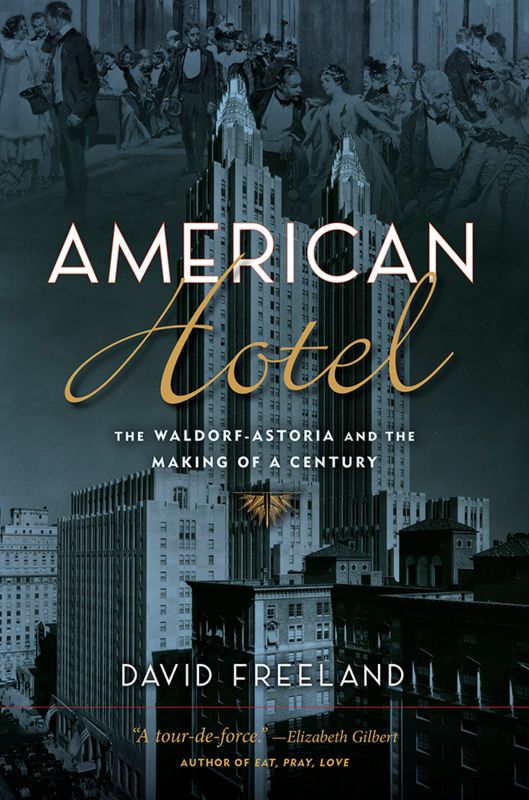

In the new book American Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria and the Making of a Century, journalist and historian David Freeland shows that despite the hotel’s luxurious reputation, it was in fact a place of democratization for most of its history. The Waldorf-Hotel “democratized elegance,” as Freeland aptly puts it, and it became a place that welcomed all without prejudice (as long as one could pay). But it was more than that. Because of its prominence, the Waldorf-Astoria actually helped set the stage for greater social reforms — by welcoming African Americans and allowing women to eat alone, for example. Freeland writes, “it’s not surprising that many of the hotel’s most publicly dramatic events were connected in varying ways, to larger turns in the social, political, and artistic life of the nation.”

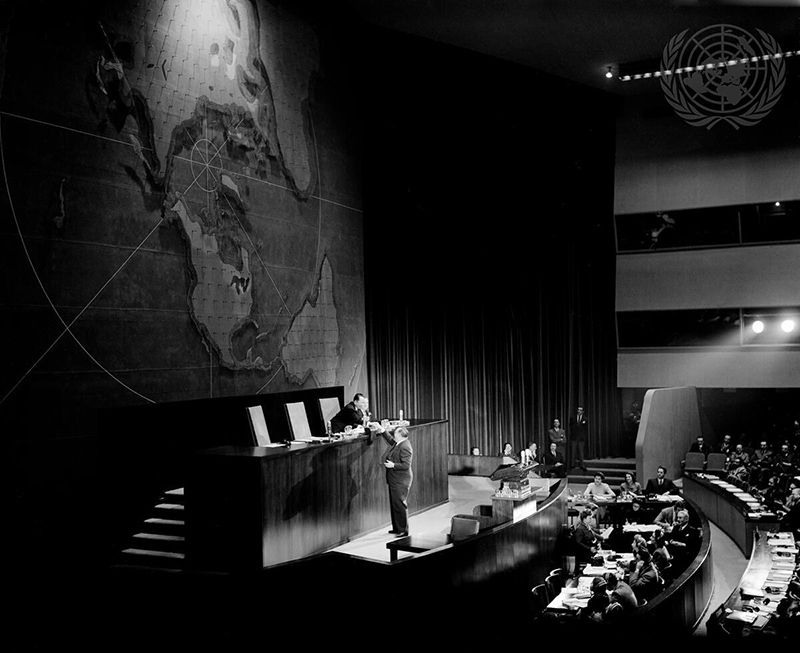

In an interview, Freeland tells Untapped New York that one of the most surprising things he discovered in his extensive research for American Hotel “was the degree of prominence it achieved on the international diplomatic stage. This development was spurred by the Waldorf’s early relationship with the United Nations.”

The United Nations? Here at Untapped New York, we’ve covered a lot about the UN, particularly its secrets and the architecture of the headquarters on Manhattan’s east side. We’ve also learned a lot about the secrets of the Waldorf-Astoria itself. The connection between the UN and Waldorf-Astoria was definitely news to us too.

The United Nations had been temporarily located in New York City since the early months of 1946 — moving from building to building. This was six years before the UN Headquarters we all know was completed. The major event of 1946 was the General Assembly, with the international delegates set to arrive in October. “New York’s selection, in 1946, as a temporary, and then permanent headquarters for the UN, created an acute spatial challenge…the question of where to house [the delegates] led to numerous logistical and (given American prejudice and its potentially disastrous implications for multiracial visitors) social dilemmas, writes Freeland in American Hotel.

Freeland tells us that “The UN Secretariat had been very concerned about the likelihood of racial prejudice, as manifested through de facto segregation, in New York City.” Many New York hotels at this time were still practicing de-facto segregation and Black Americans would consult the Green Book to know which hotels were open to them. In American Hotel, Freeland tells of the story of a 1957 visit from the finance minister of Ghana who took a road trip from New York (ostensibly to discover America) and was refused service at a Howard Johnson’s in Delaware.

Discussions between the UN and hotel manager Lucius Boomer began in April 1946 about potentially holding meeting at the Waldorf-Astoria. The hotel was also considered to be an ideal location, “one of the closest large hotels to UN temporary headquarters at Flushing Meadows, Queens,” Freeland writes, and it already had a “long-standing reputation for hosting prime ministers, diplomats, and other international guests.”

Freeland tells us that “Significantly, the Waldorf agreed to house all delegates regardless of color; in return, the UN promised to use the Waldorf for housing. The Waldorf had always been known as a host to royalty and diplomats, but this is the point at which that reputation moved to a new level.” The whole set up “saved the U.S. government from the embarrassment that occasionally resulted from situations in which America’s practices were unmasked as not living up to its ideals,” concludes Freeland.

The Waldof-Astoria’s role in national and international relations doesn’t end there of course. Freeland tells us, “At the end of 1946, the Council of Foreign Ministers conference was held inside the Waldorf – there, representatives of the U.S., England, France, and Soviet Union worked out reparations for the defeated Axis powers. The future of Trieste was determined inside of the Waldorf-Astoria — it’s hard to imagine an American hotel bearing that kind of political influence today!” And of course, even earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the likes of General Pershing, were using the special siding under the hotel, known more famously as Track 61, to come directly in and out of the hotel.

Furthermore, in the much more exclusive Waldorf Towers next door, suite 42-A, which was home to the U.S. representative of the United Nations, was used as a place where private talks could take place between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1960s. This was also exactly how the hidden apartment inside the United Nations Secretariat building was used in the 1950s.

More broadly, the Waldorf-Astoria was a center point of the ideological battles waged in the United States — over “gender equality, Prohibition, organized labor, communism, racial segregation, welfare and public relief, rights for the LGBT community,” writes Freeland, and it became a place for public figures to make a statement (and willingly engage with counter protestors).

Freeland approaches the Waldorf-Astoria as a public space and American Hotel looks at this iconic institution through this unique lens. Like all of Freeland’s previous books, the meld of storytelling, historical research, and deep knowledge of New York City make American Hotel a must-read.

Untapped New York will be hosting a talk with David Freeland to celebrate the launch of American Hotel this Wednesday May 19 at 12 PM. Tickets are free for Untapped New York Insiders.

Subscribe to our newsletter