Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

It’s possible that one of Manhattan’s most beautiful landmarked churches will soon be razed to the ground and replaced with a 19-story glass tower. Commanding an important corner on the Upper West Side, West Park Presbyterian Church opened in 1890, the original chapel having been designed by Leopold Eidlitz, architect of the renowned Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue, and the larger church by Henry Kilburn. It “is considered to be one of the best examples of a Romanesque Revival style religious structure in New York City,” wrote the Landmarks Preservation Commission in its January 12, 2010, official designation of the church as an individual landmark. It joined dozens of other individual landmarks in the West Side’s multiple historic districts, despite the church having lobbied heavily in the late 1980s for its exclusion from a district designation.

The designation report went on to say, “The extraordinarily deep color of its red sandstone cladding and the church’s bold forms with broad, round-arched openings and a soaring tower at the corner of West 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue produce a monumental and distinguished presence along those streets.” Remarkably enough in our ever-changing city that modifies and changes buildings constantly, West Park Presbyterian Church “has been little altered since 1890,” says the Landmarks Commission.

Citing economic hardship, the church’s owners have applied to the commission for de-designation, proposing to sell to a developer, Alchemy Properties, which plans to bulldoze the building and construct a 19-story tower. “There is a tendency to assume that religious properties will survive or remain unchanged,” wrote Landmark West! president Page Cowley in 2009, “as though they were immune to the boom and bust cycles of urban property development.” But New York learned long ago that isn’t true. “It is a tragic situation,” says architectural critic Paul Goldberger, “since it is hard to dispute the reality of the congregation’s circumstance.”

Now down to 12 or fewer members, the congregation has no pastor and almost no financial resources. Yet it seems to have made little effort to sell the building to an entity that would re-use and restore it. That is the church’s prerogative, of course, under the American system of property rights. But demolition would be a desolate outcome for the city and for the neighborhood.

“I find it hard to believe that there is no other possible user,” adds Goldberger, “either another congregation or some cultural organization, but I have no way of knowing how hard the current congregation has tried to find an owner who would preserve the building to avoid the sale to Alchemy. With a deal in hand there is certainly no incentive for them to look at any alternatives other than that one.”

Peg Breen, president of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, which has not yet taken an official position, also wonders about the church’s outreach: “It’s not clear how hard they tried to find a partner. Obviously we’re sympathetic with the needs of historic religious buildings but given the state of the building, they knew this was coming down the road. We’re not saying there’s not a lot of work to do there but at some point did they sit down with the congregation and look at all the options?”

Preservationists, community activists, and elected officials—most notably, UWS Councilperson Gale Brewer—have tried for years to raise money to save the building and to work with the congregation to figure out long-term solutions. Brewer and preservationists formed a nonprofit in 2009, Friends of West Park, to receive financial pledges and work with the church as well as several arts groups who were renting space. Despite progress, Friends (since reconstituted as Center at West Park) kept running up against a fundamental problem: they didn’t own the building, and the Presbyterians who did own the building didn’t want to sell. They preferred to retain the option of developing the site and reaping its financial benefits.

But before the building can be demolished, the West Park Administrative Commission, the church’s governing body, must make its case for demolition/de-designation to the West Side community via Community Board 7 and then to the Landmarks Commission. The first step in the planning gauntlet occurred at a four-hour hearing in an evening presentation to Community Board 7’s Preservation Committee on May 15th.

The only grounds for de-designation is a convincing show of economic hardship, demonstrating that the landmarked building is so deteriorated and dangerous that it imposes undue economic costs. The owners must establish that were they to renovate and restore the property they would be unable to achieve a reasonable net annual return of 6 percent of the valuation of the property, currently set at $3.46 million.

Arguing that the church is in serious disrepair, requiring significant upgrades just to comply with New York City’s various codes, the church’s lawyers, architects, and engineers offered impressive evidence. The facade is crumbling, thus the years of scaffolding, and entrances and interior routes are all non-accessible. There’s no sprinkler, no fire alarm, no enclosed stairs, no means of egress. Facade restoration alone will cost $18 million, argues the church, plus another $9.6 million for interior repairs, $2.8 million for structural repairs, $1.5 million for code compliance, and millions in miscellaneous costs bringing the total to $49.824 million. Skeptics among the hearing’s 40 participants scoffed at the figures, saying the true numbers were half that. But whatever the details, everyone agrees that restoring the church will be immensely expensive.

Following a contentious but nonetheless fairly civilized hearing, Community Board 7’s Preservation Committee voted 8-1-1 to deny the application. Next, Community Board 7′s full board will render its advisory opinion on June 7th and Landmarks will hold its hearing on June 14th, followed by the City Council, which can rule on land-use changes.

Were West Park Presbyterian Church a secular site, this debate would be far different. Brewer said at the Community Board 7 hearing that she would like the church to be sold to a nonprofit with a cultural bent, adding that she would then easily be able to allocate city funds: “If the Presbytery would sell it to a nonprofit, we would end up with millions of dollars for it to be renovated, The idea that somebody will tear this down and replace it with condos is beyond reprehensible, and I will do everything I can to preserve this building.”

The West Side has faced this church-state controversy before. The congregation of another UWS landmarked church, St. Paul & St. Andrew, which opened in 1897, voted to demolish their building in 1979. After New York City declared it a landmark in 1981, the church chose litigation, becoming the first congregation in the country to petition the U.S. Supreme Court to ban landmarking of houses of worship as an infringement of First Amendment religious freedom protections. The court declined to hear the case.

But since those fraught days St. Paul & St. Andrew has become a very active congregation within the community, making its space available to several performing arts groups, running a highly successful food pantry, housing the West Side Campaign Against Hunger, and conducting a wide range of religious services, including serving as the host sanctuary for B’nai Jeshuran. Ann-Isabel Friedman, director of The New York Landmarks Conservancy’s Sacred Sites division, argues that St. Paul & St. Andrew represents a model for the future.

Can West Park have a similar future? The politics of preservation can be combative when both big money and fundamental principles become entangled. During the 2010 landmarking dispute, West Park’s pastor, Robert Brashear, argued that “The government has no right to take away the life of a church to save a building. Nobody has taken seriously the expense of restoring this building to functionality.” Saying that the legal requirements for restoring a landmarked building had severely decreased the price of the building, making it less desirable to developers, Brashear set its post-landmark value at $7.5 million, far less than its previous $30-35 million.

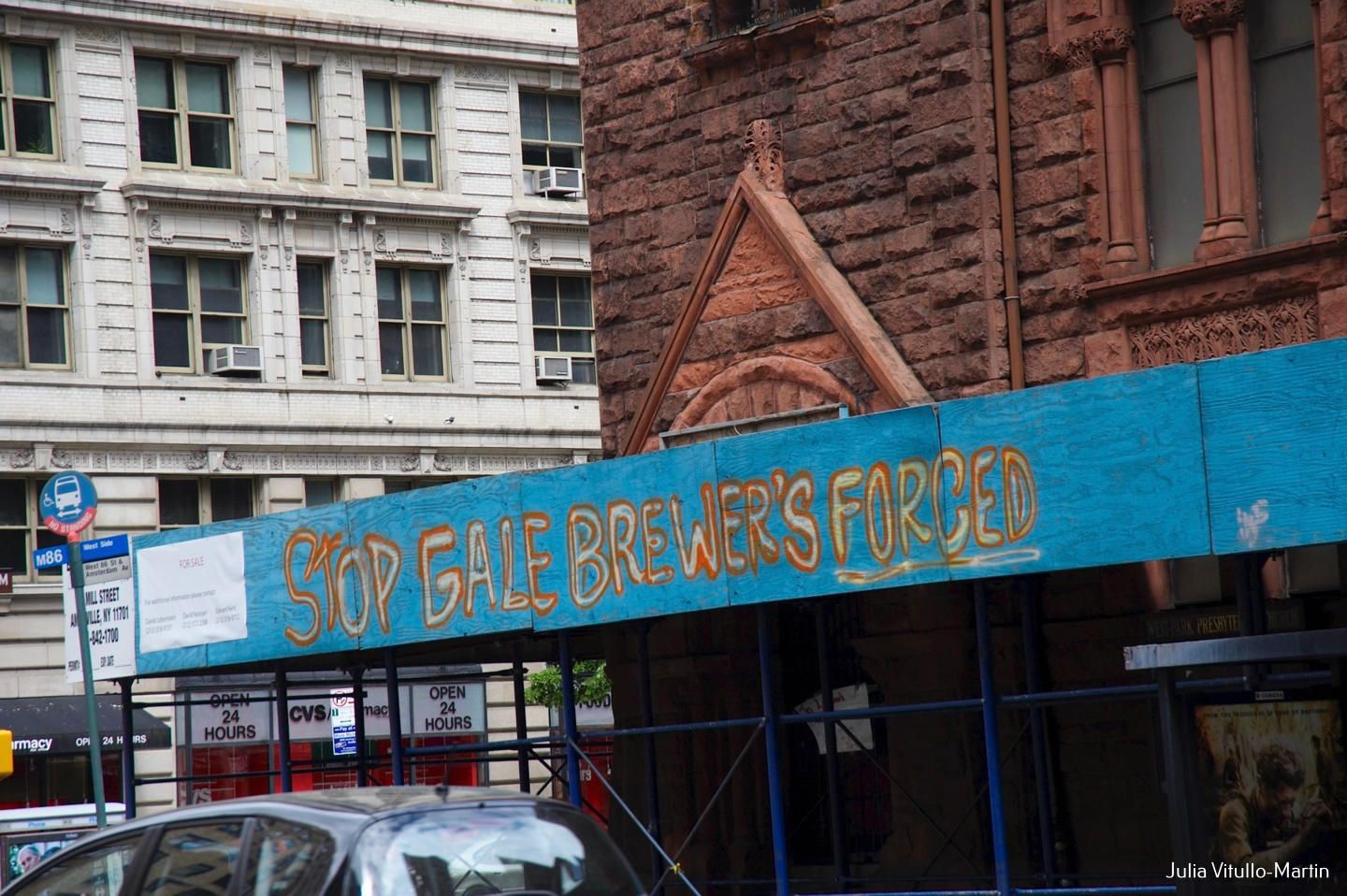

Some congregants, such as West Park elder Hugo Meneses, concluded that talk was not enough. He was arrested by police during an April 2010 protest while he tried to paint “Stop Gale Brewer’s Forced Landmarking” on the sidewalk scaffolding. “The concept of forced landmarking is unconstitutional,” he told a Presbyterian Church publication. “The so-called preservationist groups have little care about the effects landmarking would have on the congregation or the church itself. Their only concern is trying to preserve the building without making any effort to help financially. They have been trying for 25 years to have this church landmarked. They make big promises, but they are empty promises. How much money have they raised or given to help restore the church over the last 25 years? None.”

Friends of West Park obtained pledges for several hundred thousand dollars and Brewer is confident that she would be able to raise millions of dollars were the church to be sold to a nonprofit. Everything always comes back to ownership. “We proposed a $2 million purchase price three years,” says Susan Sullivan, a neighbor who is now on the board of the Center for West Park, “The Presbytery said no way. Then we asked for a long-term lease. They said no. Our current proposal to buy is $5 million.”

Landmark West! president Cowley says, “Here’s what I propose: we can raise the money. We don’t have to do the restoration in one go, can do it in phases, we can find a way. We made the right choice when we designated the property, now our charge is to locate people and sponsors to save this building.”

It’s not just the church’s architectural heritage that puts it at center stage on the West Side. Its eminent activist and spiritual legacy is matchless. Kathryn E. Holliday, author of a sort of architectural biography of Leopold Eidlitz says It was no accident that the Presbyterian Church hired him in the early 1880s. He had been America’s first Jewish architect and a proponent, like his contemporary Louis Sullivan, of organic architecture. He described his West Park chapel as “muscular,” appropriate for the evangelical mission of the Presbyterian Church.

From its earliest days West Park promoted “ethnic inclusion,” wrote the Landmarks Commission in 2010. Its socially progressive pastor, Anson Phelps Atterbury, invited Chinese congregants to worship at the church at the peak of anti-Chinese hysteria in the 1880s. Over the decades West Park fulfilled its spiritual mission in part through its continued strong community activism, hosting principled rebels like the Berrigan Brothers, and sheltering AIDs protestors, among many others. It was the first home of such crucial New York institutions as Joe Papp’s Shakespeare in the Park and God’s Love We Deliver.

Today the church building is home to many arts groups, including artists, dancers, and musicians. The Russian Arts Theater & Studio, for example, opened its production of George Orwell’s Animal Farm on May 12, donating a portion of the ticket proceeds to organizations helping refugees of the Ukrainian crisis. Artistic Director Aleksey Burago says that Orwell’s scathing satire of the Soviet Union and its stealthy descent into totalitarianism offers many lessons for today’s world.

Will the church building continue to anchor its West Side neighborhood with its beauty and heritage? The Landmarks Commission is generally loath to overturn its designations. Only 19 hardship applications have been filed since the commission’s creation in 1965. Of those, thirteen were approved, four denied, and two not voted on. These numbers might be reassuring to preservationists but the past may not be prologue here. It’s likely that no previous church hardship application ever had the big legal and engineering guns that West Park has produced.

“It would be an awful loss for preservation and horrible for the neighborhood,” says Paul Goldberger, were de-designation granted. “But it’s hard to be optimistic. It’s interesting to note that of the few hardship de-landmarkings there have been, one of them is just a few blocks away on West 79th Street, where the mid-block Mount Neboh Synagogue was replaced by a banal apartment building. Here, the impact would be far greater because of the prominent corner site.”

The summer Landmarks Commission hearings will be a test of many cherished principles, pitting religious property rights against historic preservation. It will also be the first serious preservation challenge confronting our new mayor, Eric Adams, his Landmarks Commission, and the many newly elected members of the City Council. A sobering reminder to preservationists: The City Council in 2003 overturned the designation of the exterior of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Julia Vitullo-Martin, who lives in the Belnord, across the street from West Park, can be reached at @JuliaManhattan. Next read about the secrets of the Upper West Side.

Subscribe to our newsletter