Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Bill de Blasio already has a parody Twitter account (@BilldeBleezy) in his honor. The mayor elect, who will assume office in January as the 109th chief public official of the City of New York, represents a major paradigm shift in the political drumbeat in the most visited city in United States. His predecessor, three-term serving billionaire Michael Bloomberg, has a Twitter parody, too, but de Blasio’s will no doubt be of a decidedly different tone. For starters, his Spanish is markedly better.

Last week, de Blasio was elected with almost three-quarters of votes, a margin that should surprise no one in a city where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans 6-to-1. Yet, this will be the first time New York has a democratic mayor since 1993, when incumbent David Dinkins lost to Republican Rudy Giuliani, in an election and mayoral administration that some say changed the history of the city. Indeed, in the final weeks before the election, de Blasio’s Republican rival Joe Lhota, an longtime ally and former Guiliani staffer, put out an ad that threatened a return to early 1990s New York (high murder rates, graffiti-filled subways cars, rampant muggings, and all) should de Blasio be elected. (We should be so lucky to ever see rents that low again.)

Despite the stacked political odds, and a crowded primary field that included Bloomberg’s hand-picked successor and New York’s most infamous Twitter politician, de Blasio managed sweeping victories, both in the primary, where he unexpectedly garnered the 40% of the vote needed to avoid a runoff, and in the general election.

But what exactly has de Blasio promised New York, and how will it affect the shape and shaping of the city? The central focus of his campaign was to address growing inequality. Beginning with the youngest New Yorkers, he has touted universal Pre-Kindergarten as a central tenet of his campaign platform. Education is generally a crowd pleaser, but this proposal brings up the simple logistical question of where exactly these tens of thousands of Pre-K seats will be housed. If the new mayor does see us through on the promise of a classroom seat for every four year-old, we can safely assume some classrooms will have to be built. This sounds like good news for architects and builders.

In addition to classroom seats, de Blasio has pledged to preserve or create 200,000 units of affordable housing, without the usual huge tax breaks to developers. The projected success of that proposal is mixed; some say that without incentives, affordable housing simply will not be built. As rents continue to rise in New York, this plan could be an important counter-action to rapid displacements and gentrification, which has deleterious effects on the diversity and stability of neighborhoods.

On transportation, de Blasio has proposed the creation of a citywide Select Bus Service (NYC’s version of a Bus Rapid Transit network) with more than twenty lines, connecting currently transit underserved communities to transit hubs and jobs. On his list of SBS routes are Co-op City to the West Side, Long Island City to LaGuardia Airport, Flushing to Washington Heights, Bay Ridge to Jackson Heights, and the Rockaways to Jamaica. On the ever hot and debated topic of bicycle infrastructure and Citibike, an effort championed by Bloomberg under the leadership of DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan, de Blasio has pledged that bicycles will count as 6% of vehicle trips by 2020. His transportation plans articulate commitment to relatively low-cost connectivity solutions, that will make getting to work and living in New York easily for millions of people.

But while de Blasio has painted himself an advocate of increasing multimodal mobility, his stance when it comes to transportation and public space is not uniformly progressive. During a mayoral debate, he called Sadik-Khan a “radical,” in the less than positive way (quite the unexpected insult from a man who worked as an organizer alongside Nicaraguan Sandinistas). At the same debate, when asked “Would you take out the tables and chairs from Times Square and Herald Square and re-open Broadway?,” de Blasio answered, “I have profoundly mixed feeling on this issue. I’m a motorist myself and I was often frustrated — and then I’ve also seen on the other hand it does seem to have a positive impact on the tourist industry.”

For urban planners, this comment has alarming implications about de Blasio’s knowledge on current progressive thinking about how to create better cityscapes, and betrays his lack of familiarity with the data that points to the uncontested success of the Herald Square and Times Square plazas. Given that de Blasio’s campaign centered on the principle of giving an equal chance to all New Yorkers, many transportation advocates are baffled at how he might think to put anyone other than pedestrians (the ultimate egalitarian mode) first.

In an interview on the Brian Lehrer Show the day after the debate during which he pooh-poohed Sadik-Khan and seemed lukewarm on the transformation of Broadway, de Blasio could not seem to articulate credit to pedestrian plazas as anything other than a type of traffic-calming device. Perhaps, in this particular arena, he will need to confer with progressive transportation experts (someone send him an all-caps memo, please!) in order to consider rethinking his position. The best planners can do is seek to advocate for the safest and most equitable choices at game time. Hopefully someone will familiarize him with the Braess Paradox, the mathematical theorem that shows that traffic does not deteriorate when public space is added.

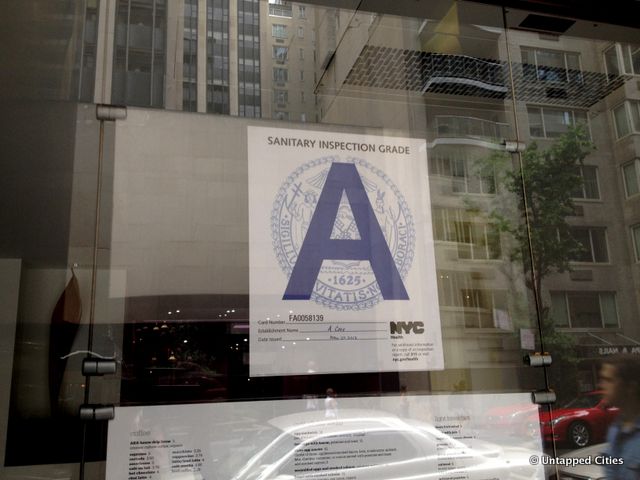

There are endless big plans to be made over the next four years. New York and its mayoral administrations are built on grand schemes, the promise and premise of large-scale change, but urbanites know, sometimes the true gifts (we’ll leave the Devil shout-outs to Justice Scalia for at least another month) are in the details. Among the countless smaller-scale adjustments de Blasio has pledged to make are changes to the fine teeth of the restaurant sanitary grade inspection system, which levies damagingly high fines for violations that have nothing to do with food quality or cleanliness (such as a minimum $400 fine for subjective judgments made by inspectors about the best way to store sanitized utensils). In this kind of attention to detail, de Blasio demonstrates an understanding and, more important yet, and empathy for how large bureaucratic decisions can affect the little guy, and his commitment to cultivating a kinder playing field.

Only time will tell how effectively de Blasio will go about building the networks needed to make New York more accessible to the 8.3 million people who currently call the city home. Less than one-eighth of the city’s population voted in the general election, and less than 10% (752,604 New Yorkers voted for him on November 5) cast the votes that put him in office. But for those who did elect him, de Blasio seems ready to serve, both them and the rest of the city. During his victory speech at the Park Slope Armory, he buoyantly proclaimed, “The people of this city have chosen a progressive path. And tonight we set forth on it, together, as one city.”

The people will be waiting. And planning. And building. And hopefully enjoying safer and shorter commutes. Stay tuned.

Subscribe to our newsletter