Last Chance: The Annual Orchid Show Soars at the New York Botanical Garden

The vibrant colors of Mexico come to NYC for a unique Orchid Show at NYBG!

Historically, Union Square has been the site of many meetings, demonstrations and speeches, including rallies for the Union during the Civil War, the nation’s first Labor Day parade in 1882, the first suffragette parade, an anarchist bombing, and the funeral processions of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Jackson. Union Square has continued its role as a gathering place for political protest through the Vietnam War into the present day, and in the demonstrations over the weekend surrounding the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Union Square once again become one of the public spaces to manifest social unrest. Like many places in New York City and elsewhere around the country, peaceful protests during the day gave way to more violent clashes in the evening.

NYPD commander putting out a trash fire on Union Square west, just as FDNY rolls up. It sounded like he was on the phone with his wife. “What am I doing right now? I’m putting out a fire!” May 30, 2020. Photo and caption by Joseph Anastasio.

Quite lost to history is the former Union Square Pavilion (also known as the Women’s and Children’s pavilion) located on the north end of the park, which became a de-facto stage for protest and demonstration that was designed by park architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to accommodate a public requirement for mass meetings. According to Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, author of Design for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square, “When thousands of working-class New Yorkers marched around Union Square in triumphant assembly in 1882, they claimed one of the city’s premiere public as their own. For the next fifty years, unions and political groups used the Square as a stage for elaborately choreographed presentations of working-class power and solidarity designed for both internal and external audiences.”

In order to use the park for a meeting, organizers would have to apply for a permit with the Parks Department. Merwood-Salisbury writes that “while the police had the ability to deny permits for public gatherings, they had seldom withheld permits in order to preemptively supress political gatherings.” And in fact, the police would use Union Square themselves for public demonstrations as well, to “establish an image…[of] the city as a whole, as a stronghold of stability and lawfulness.”

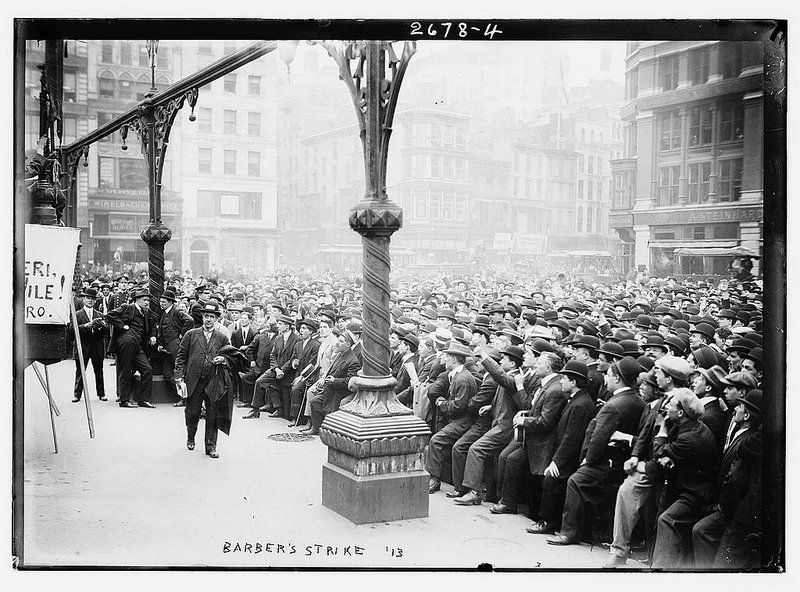

1913 Barber’s Strike. Photo from Library of Congress.

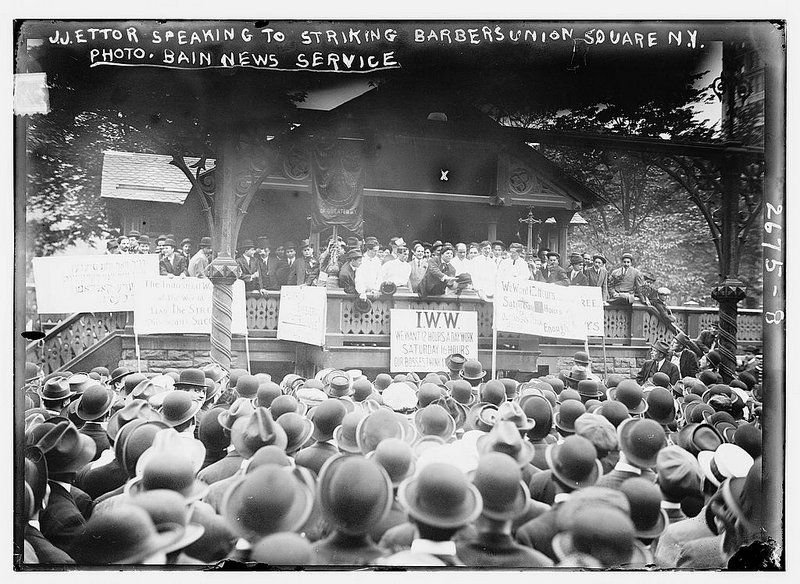

The pavilion, where much of the events took place was a wooden structure designed in the Victorian Gothic style, akin to the buildings designed by Olmsted and Vaux like The Dairy in Central Park or those in Prospect Park. In front of the building was a porch with staircases rising up from the ground. In front of the porch were the stands, a platform close to the ground but slightly elevated delineated in space from the public by elaborately ornamented columns and railings.

Labor Leader Joseph James Ettor Speaks at the 1913 Barber’s Strike. Photo from Library of Congress.

In addition to adding the pavilion, Olmsted and Vaux, who had completed Central Park in 1857, changed the design of Union Square Park significantly. An enclosed fence was removed, the sidewalks around the park widened, new trees planted, and a muster ground for the military added — all of which increased space for public gathering.

In March of 1908, Selig Cohen (also known as Selig Silverstein), a Russian member of the Anarchist Federation of America, threw a bomb during a socialist meeting in Union Square. The bomb prematurely detonated, killing a bystander and mortally wounding the bomber. Image from Library of Congress

The 1890s saw a crackdown on public gathering, with the increase in anarchist activities around the city. But, according to Merwood-Salisbury, an interesting experiment began after the detonation of a bomb in Union Square in 1908: “Influenced by a progressive municipal administration, the Police and the Parks departments fundamentally changed their attitude regarding mass meetings. Parks Commissioner Charles B. Stover and Police Commissioner Arthur Woods promoted a reform attitude to the control and use of public space, arguing that the role of the police was to protect rather than repress public speech, even when it was highly contentious…In this way, Union Square was momentarily transformed from a highly dangerous space, the literally explosive home base of a nationwide anarchist threat, into a fragile test case for progressive attitudes to the protection of public assembly for the purpose of political expression.”

1914 May Day gathering ( (Suffragettes caption mislabels the event and date, as noted by the Library of Congress). Image from Library of Congress

Photographs from the Library of Congress show organized, peaceful demonstrations at the Union Square pavilion in both 1913 and 1914. In one, labor leader Joseph James Ettor speaks to striking barbers during the Brooklyn Barbers’ Strike of 1913 at the Union Square stands. The Industrial Barbers Union was an organization within the Industrial Workers of the World. They demanded a shorter, 12-hour workday and a 6-day work week. The union was granted their demands. In 1914, a socialist and labor union demonstration took place on International Labor Day (May Day) in 1914.

Photo and caption by Joseph Anastasio.

Amidst current events, the history of New York City’s legally mandated spaces for mass meetings and demonstrations, as well as the recorded detente initiated by the city’s police force in regards to public gathering is worthy of note. If public spaces were designed once again to accommodate demonstrations and if privatization of public spaces had not become the prevailing trend, would the city see the same level of destruction to private property during periods of social unrest? The story of Union Square seems to indicate that design, and how we conceive of the functions of public space, can even have a direct impact on how policing is done. And it would certainly provide formal, physical outlets for the populace to express their beliefs, with the understanding that the demonstration spaces are in themselves provided by the city.

The history of demonstrations in Union Square is included in the book Broadway that I wrote which was published in 2015. This is how I first came across the legal mandate for mass meetings in New York City and the existence of this former pavilion in Union Square. Next, check out 10 riots that have taken place in NYC’s history, over Shakespeare, flour and more.

Subscribe to our newsletter