Vintage 1970s Photos Show Lost Sites of NYC's Lower East Side

A quest to find his grandmother's birthplace led Richard Marc Sakols on a mission to capture his changing neighborhood on film.

Until the 1960s, single women traveling alone were often not permitted to check into hotels or dine in restaurants unless accompanied by men who could vouch for them. Although women had won the right to vote in 1920 and began to enter the workforce in droves during the same decade, their lives were often controlled by laws and regulations intended to maintain their safety and “preserve their virtue” before marriage. Single women seeking independent careers in New York often faced the obstacle of finding safe, affordable housing, resulting in the establishment of women-only hotels. From the 1920s to the 1970s, New York was home to dozens of women’s residential hotels, which offered a respectable and affordable place for women to stay while providing them with social and professional connections.

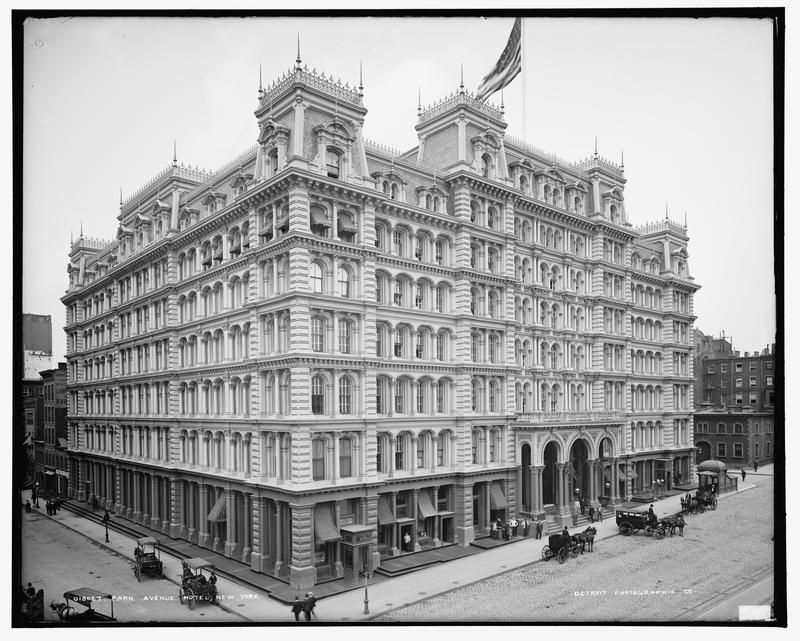

New York’s first “Working Women’s Hotel” was founded by Irish businessman Alexander Turney Stewart and opened in 1878 on Fourth Avenue, now Park Avenue, between 33rd and 34th Streets. Named The Stewart Hotel for Working Women and often simply called The Women’s Hotel, Stewart envisioned it as a place for “industrious young women… to foster individuality and self-dependence.” One of the largest hotels of its time, it featured an elegant cast iron structure composed of columns, lunettes, and a courtyard. It could house up to 1,500 working women. Women could rent a private room for seven dollars a week and a shared room for six dollars. This first foray into women-only hotels was short-lived. In June 1878, just forty-five days after the hotel opened, it was closed and rebranded as the luxury Park Avenue Hotel. Citing a lack of patronage, the hotel managers opened it up to guests of both sexes to maximize profits. The building was demolished entirely in 1927.

While the city may not have been ready for Stewart’s women-only hotel yet, there were a plethora of “moral homes” to house working women of the late 19th century as they flocked to the city to find factory, retail, and secretarial work. These homes were often run by Christian organizations with strict rules and restrictions designed to reinforce good behavior, such as morning prayers and a ban on men except for supervised visits in the parlor. Women were watched over by house matrons known as “mothers,” who monitored their behavior and instructed them in middle-class morals. By 1898, 46 cities had homes for working girls according to a report by the Department of Labor. In New York, one such home was the Young Women’s Christian Association’s Margaret Louisa Home, which opened in 1891 at 14-16 East 16th Street. Rent was to be paid in advance, and the facilities were scarce, with no cooking and washing facilities. Lights were out by 11pm. Residents were milliners, governesses, librarians, and saleswomen. Requirements for admission included “good character,” “self-supporting,” and “respectability.”

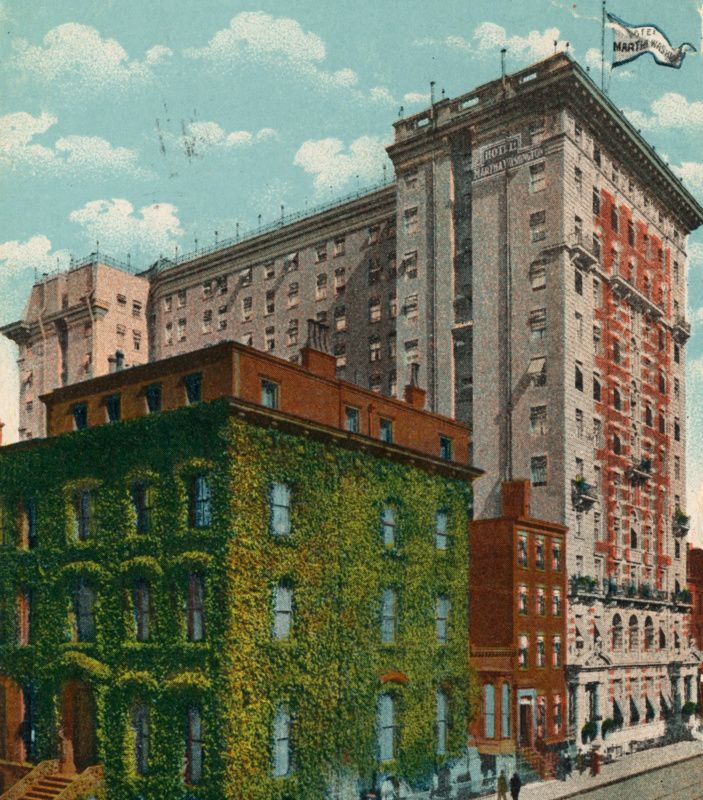

The Martha Washington Hotel, the first exclusive women’s only residential hotel, opened on March 2, 1903, at 30 East 30th Street in the Rose Hill neighborhood of Manhattan. Initially, the elegant Renaissance Revival-style hotel banned male guests, smoking, and alcohol. It was operated by an almost all-female staff. The Martha Washington Hotel was designed for a new generation of college-educated women who intended to pursue professional careers, such as businesswomen, teachers, musicians, writers, doctors, and nurses. The hotel became the headquarters of a feminist group, the Interurban Women Suffrage Council. Upon its opening, The Sun newspaper reported:

Between three and four hundred women are now making themselves at home at the new Martha Washington Hotel for women on East Twenty-ninth street, New York. They moved in one night, bringing with them piles of baggage. There were no exercises. The women walked in and took possession, just as calmly as a crowd of drummers or confirmed travelers might. Women of every description were there. They included professional women, women with their hair rolled back from high foreheads, women truly frivolous and feminine in fluffy sorts of evening frocks, women who carried lorgnettes [i.e., eyeglasses] and missed nothing, the shyer kind who shrank behind the shelter of some potted palm, women from Brooklyn, women from Terre Haute, working women and confessed idlers.

The Martha Washington Hotel was an immediate success, with luxury amenities for its upper-class clientele, including a drug store, manicurist, and tailor shop. It caused such a sensation that in 1904 the New York Times reported that organized tours now passed in front of the hotel: “The observation automobiles have now included it among the places of interest to point out to the out-of-town sightseers, and one would suppose that the inmates were a new kind of freak that had not yet been classified in a museum or menagerie.” Notably, the hotel offered women a new form of freedom that could not be found in the “moral homes” and broke a taboo in 1933 when it applied for a liquor license. Its famous guests included poet Sara Teasdale and actresses Louise Brooks and Veronica Lake. The hotel building survives today as the women-run Redbury Hotel.

In the 1920s, after women had earned the right to vote and increasingly began to enter the professional sphere, many new women’s hotels opened up: the Virginia Hotel, the Sutton, the Hotel Irvin for Women, The Allerton, and the Hotel Rutledge among them. In 1929, a New York organization even held a contest and offered a six-day trip to Bermuda for a “business girl” who submitted the winning name for a new women’s hotel. During their heyday from the 1920s through the 1970s, women’s hotels provided a place where ambitious women could make friends, pay affordable rent, and get a fresh start in the city. The luxurious Allerton Hotel, built in 1927, featured a ballroom, a library, and a rooftop garden. The art deco Beekman Tower Hotel was built in 1928 as a club and hotel for women in sororities, symbolized by the Greek letters on the facade, before shifting to non-sorority all-gender housing in the 1930s.

Perhaps the most famous, luxurious, and enduring of the women’s hotels was the Barbizon, a neo-Gothic skyscraper that opened in 1927 on the corner of East Sixty-third Street and Lexington Avenue. Memorialized as the Amazon Hotel in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and in Joan Didion’s “Goodbye to All That,” the Barbizon also hosted actresses like Grace Kelly and Liza Minnelli, the writer Peggy Noonan, and the future First Lady Nancy Reagan. The hotel could accommodate over seven hundred women and featured amenities including a swimming pool, gymnasium, library, lecture halls, music rooms, and a rooftop garden. Guests could enjoy free afternoon tea and a lobby with a hairdresser, dry cleaner, pharmacy, and hosiery and millinery shops. These amenities were designed to appeal to middle and upper-class young professional women. The hotel maintained an air of propriety by barring male guests from residential floors.

The Barbizon Hotel cultivated a certain type of young, white, well-educated, and professional women. Undoubtedly exclusionary, the hotel screened its residents by looks and age: aspiring residents under 28 were assigned “A” grades, while those above 28 received a “C”. Artist and writer Barbara Chase was likely the first Black woman to stay at the Barbizon when she also became the first Black woman to be accepted as a guest editor at Mademoiselle magazine in the summer of 1956.

The hotel required letters of recommendation and expected its residents to actively pursue employment; however, it also helped to open professional doors. The Barbizon featured club rooms for some of the Seven Sisters schools, and maintained special relationships with elite employers and institutions. For example, students from the exclusive Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School had a private dining room and lived on two floors of the Barbizon while they learned typing and shorthand. The Barbizon was also home to models from the John Robert Powers agency, a high-powered modeling agency whose models appeared in Sears or Montgomery Ward catalogs.

Beginning in the 1930s, the women’s magazine Mademoiselle founded a guest editor program that offered college students prestigious summer internships while housing them at the Barbizon. Many of the guest editors went on to successful writing careers, including Joan Didion, Sylvia Plath, and Gael Greene. Plath fictionalized the Barbizon in her novel The Bell Jar as the Amazon, including a real-life scene where she threw all of the clothing she had bought for the internship off the hotel’s roof. Didion began her essay “Goodbye to All That” with her arrival in New York for the program. Greene later wrote a series of essays about the women who lived in the hotel, designating some of them “lone women” who choose to stay permanently for work or because they would or could not marry. These literary portrayals of the Barbizon helped to enshrine the hotel in popular midcentury culture as a symbol of the increasing opportunities available to women. Both a respectable place with strict regulations and a luxurious hotel offering metropolitan freedom to its residents, the Barbizon came to symbolize the plethora of choices available for independent career-minded city women, both those making their way in the professional world and those seeking to enjoy the best of New York’s high life.

By the 1970s and with the rise of the women’s liberation movement, women’s hotels began to fall out of favor. By 1979, the New York Times counted just three women-only hotels in the city. The Barbizon, the Martha Washington, and The Allerton House. At that time, their luster and luxury had worn off. The Barbizon began accepting male guests in 1981 and was converted to condominiums in 2006. Some of The Barbizon’s original residents continue to live in the rent-stabilized rooms they rented decades ago. Many of the formerly women-only hotels, such as the Redbury, continue to survive in new iterations. The Allerton lives on as Hotel 57. The fifty-year heyday of New York’s women’s hotels is a reminder of the increasing professional opportunities available to women in the big city, and the many obstacles they had to conquer in order to forge a life of freedom and independence.

Next, check out 10 Secrets of the Barbizon

Subscribe to our newsletter