Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

For some the addition of music or buskers on the bus, train or metro is a welcome accessory to their daily commute. In Madrid, as of lately I have seen more and more artists take the underground or stake claim in Puerta del Sol and Plaza Mayor as an opportunity to earn their daily bread. I’ve seen them surrounded by the metro’s white tiles in a corner next to the escalators, riding alongside the other passengers with their guitar bag or pull-cart of a speaker or waiting at high traffic areas for commuters to finish their lunch hour or work day. The other day someone told me that they had experienced a full-on Shakespeare troupe in the metro–how cool!

However, another day riding the subway I encountered a new circumstance. Two security guards ushered a busker off the metro–without force–while the entertainer was mid-song. I asked one of the guards why they had done that, “Is it illegal to play music on the metro?” She answered that it is prohibited only when it is a nuisance or annoyance to the passengers. Therefore, it could be perceived as permitted in wide hallways, during hours of slow commuter traffic or if no objections are made.

Which led me to contemplate, how do we perceive art? What is bothersome to us? Will we allow ourselves to be introduced to new forms or are we only willing to pay for something if we choose to enter the four walls housing the exposition, act or artwork? How then does urban art, an “intrusive” form of art–being that it is never up to us if we see it or not, it is just there–affect Madrid’s civilians and which artists are changing our perceptions?

According to another set of policemen, la guardia civil, graffiti is illegal on all accounts in Spain, minus in situations where an artist has been commissioned to produce something and the legal paperwork has been filed to validate this agreement.

A store front window is decorated in black and white, likely the outcome of a hired artist and approved city codes.

A store front window is decorated in black and white, likely the outcome of a hired artist and approved city codes.

Apartment building mural in the Lavapiés neighborhood. Calle Lavapiés #17, designed by Cristina Gayarre.

Apartment building mural in the Lavapiés neighborhood. Calle Lavapiés #17, designed by Cristina Gayarre.

There are over forty-four museums in the Spanish capital. If you are interested you can find a wide variety of sculptures, classic pieces, modern, theater, comedy, photography and specialty museums, like the Naval Museum or even 18th century garments. Street art however is a rarer sight, especially along the tourist path running from el Museo Prado to the Palacio Real on the far west end of the city. Splashed across shuttered store fronts, trains out towards the city limits or on crumbling walls of deserted warehouses you are more likely to see “bubble” signatures or tags of that nature.

I suppose the phenomenon in Madrid starts with the definition of graffiti. We are generally, from a young age, taught or gather from the media that graffiti has a negative effect on society.

graf ·fi ·ti [gruh-fee-tee] noun

1. plural of graffito.

2. ( used with a plural verb ) markings, as initials, slogans, or drawings, written, spray-painted, or sketched on a sidewalk,wall of a building or public restroom, or the like: These graffiti are evidence of the neighborhood’s decline.

The second influence is our government’s perception. If a city, district or nation bans or allows this type of expression from its residents or tourists, the city’s entire persona can be altered accordingly. Take a look at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, as Michelle the founder of Untapped Cities called attention to the city’s aggressive and prismatic landscape in her featured article in the Huffington Post. Is there a coincidence that this city is home to the happiest people on Earth?

Getting away from adverse connotations of graffiti to educating the citizens about street art is in the hands of the artists. People will need to be surprised, awed and moved. Tagging is no longer the answer for grabbing attention, and defacing property isn’t the motto of today’s street art icons. Murals, small objects in wall corners or building skins need to be unique and speak to the population. Spanish artist Escif is quickly gaining the attention of the urban art scene for his international work, however the majority can be found in Valencia, Spain, where he resides. Escif paints rather politically themed murals and one-offs with a minimal color palette. He also keeps a YouTube channel to display his works to fans.

Madrid has proven to be a little slower to adapt. There are less artists than say Paris or New York City, but according to word on the street, the artists that roam the capital are active in what they do.

Mostly found in the neighborhoods of Malasaà±a and Lavapiés, you should keep your eyes out for 3ttMan, a multipurpose artist who in 2011 headed a campaign based on cement carvings. He worked in broad daylight, blending in as a construction worker, yet still received threats and fines for his expressions.

“Mas obra, menos arte, More construction, less art,” states this piece by 3ttMan on Calle de la Luna.

“Mas obra, menos arte, More construction, less art,” states this piece by 3ttMan on Calle de la Luna.

The door of a small storage-space becomes the canvas for an urban graffiti artist in Madrid.

The door of a small storage-space becomes the canvas for an urban graffiti artist in Madrid.

REMED, a Frenchman who claims Madrid as his adoptive city, creates colorful and generally large scale pieces, e1000ink specializes in surreal and 3D paintings, Neko, very active in Madrid, produces stickers, posters, stencils and neon light fixtures that take the place of advertising modules or telephone booths. Sam3 has been gaining more national and international attention, arriving to be known in London and Portugal. His most recent billboard makes references to the recortes, or budget cuts that have been hitting Spain’s state, education, health and cultural programs with drastic cutbacks. dosjotas who has a gift for the irony, reinvents street signs, garbage collection notices, public advertising or state information with a twist. Only those who read the fine print or recognize the sarcasm in the changed landscape will know he has been there.

2009 mural by 3ttMan and REMED on Calle de la Luna in Madrid’s city center.

2009 mural by 3ttMan and REMED on Calle de la Luna in Madrid’s city center.

A fresh fish shop is adorned with the art of 3ttMan on Calle del Noviciado.

A fresh fish shop is adorned with the art of 3ttMan on Calle del Noviciado.

Finally, Nuria Mora or just Nuria in the art world has been painting geometric shapes with “girly” touches–floral or gingham effects–for years now. She has a tendency to choose attention grabbing locations in the touristic center of the city. For a large mural on Calle de Cedaceros she worked 7 hour days for a finished product that mixes the industrial feeling of the street with her daintiness. When I went to visit, it had already been covered by others, more proof that these pieces are so temporary, or at least always straying further and further from the artist’s’ original intentions.

Pastels and flowers merged with city landscapes in Madrid’s historic center. Mural by Nuria.

Pastels and flowers merged with city landscapes in Madrid’s historic center. Mural by Nuria.

There also exists a movement of people who are dedicating themselves to capturing this art, documenting it before it is removed, worn-away or splashed over, such as Madrid based photographer Guillermo de la Madrid and artist Alberto de Pedro. Or bloggers dedicated to making Madrid known to the rest of the world.

Today street art is more mainstream, once underground sites like Street Art News and Unurth, give a daily update of happenings and discoveries around the globe to thousands of fans, through various social media platforms. But like anything that goes big, the anti-movement will likely be even more powerful, aware and present of the opposition. Although this Guardian article dates back to 2007 and it speaks to the UK’s position on street art, its trifle nature remains an international current affair. The answer quite simple, those creating the pieces do less harm than those removing it.

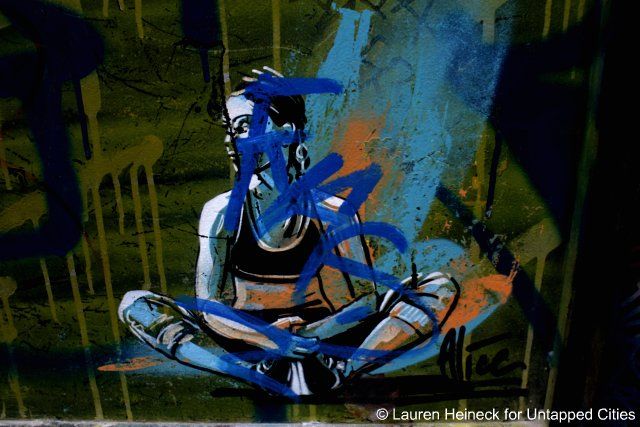

A moment too late, a small piece by street artist Alice is covered by a tag in Madrid’s Malasaà±a district.

A moment too late, a small piece by street artist Alice is covered by a tag in Madrid’s Malasaà±a district.

You may wonder what makes certain cities more artsy than others. Is it rebellion? For instance Parisians are more likely to jump the metro and they have a history of being flamboyant protesters. Are they creating an environment for anti-system procedures and free expression? Is it something already present in their culture? If so, Madrid should be almost at the top of the list with Velázquez and Goya as a base. Or has the Spanish capital been too far gone from the creative nucleus, as artists in the early 20th century fled to Barcelona, France and beyond? I don’t have the answer for you, I can’t tell what moves the artistic and inventive cooperative of the city. But I’d be willing to guess that Madrid will show more expression in the coming years, that artists will be passing through or settling permanently between which they’ll leave their mark on the city. Why? Because Madrid is in transition. The unrest of politics, unemployment, civilian rights and a renaissance or revolt of what it means to be “Spanish” will speak itself in the form of art. Or at least I hope so, because a city is bare, weak, lacking energy and character if its artistic set cannot be lauded and admired on display for the public.

“La calle es de todos, es para transmitir el arte que cada uno de esos artistas urbanas lleva dentro.”

“The street belongs to everyone, it exists so that every artist can transmit what they carry inside to the masses.”

– Mario Suárez, Journalist and autor of urban art books.

Follow Untapped Cities on Twitter and Facebook! Get in touch with the author @jamon_y_vino

Subscribe to our newsletter