“The underground galleries, organs of the large city, would function like those of the human body, without revealing themselves to the light of day. Pure and fresh water, light, and heat would circulate there like the diverse fluids whose movement and maintenance support life. Secretions would take place there mysteriously and would maintain public health without troubling the good order of the city and without spoiling its exterior beauty.” [1]

”” Baron Georges Haussmann, 1854.

The analogy Haussmann draws between the underground and the human body has roots in Saint-Simonian philosophy, a prevalent philosophical movement in nineteenth-century Paris. It is believed that Haussmann’s convictions are in fact a distillation of this thought, as the Saint-Simonians “favored an even more elaborate corporeal metaphor of renovated Paris as a woman complete with fountain-breasts and the works.” [2] Nevertheless, an underground system is not, and cannot ever truly be contained below the surface as Haussmann desired but in fact manifests on the exterior of a city through deliberate built structures, such as manholes and hatches, and accidental seepage.

England’s urban systems were evolving in tandem with Paris, when “The Great Stink” of 1858 catalyzes the construction of the modern London underground. The particular potency of the pollution that summer prompted lawmakers to finally enforce and enact public health and environmental legislation: “It was a smell that arose from the banks of the Thames, enveloping anything with the bad fortune to be downwind of the river and forcing even such august institutions as Parliament and the Law Courts to close not only their windows but, when the stench was bad and the temperature high, their entire offices as well.” [3]

The word “sewer” is defined in old English as “seaward,” which described the open drainage ditches that sloped downwards to the Thames.[4] The Oxford English Dictionary traces the origin of the word to the old French word seuwiere, “a channel to drain overflow.” [5] By the nineteenth-century, the waste from these conduits eventually overwhelmed the ability of the river to self-cleanse. Despite attempts by Henry VIII, King Richard the II and other monarchs to address waste management, unprecedented population growth connected with the Industrial Revolution ultimately lead to the “Great Stink” of 1858. The first Public Health Act is passed in 1848 but the more comprehensive 1875 act provides “Britain with the most extensive public health system in the world.” [6] This act specifically addressed the problem of contaminated water supply and sewage. It had become clear that simply dumping waste upstream or burying it was not the solution. The smell withstanding, three cholera epidemics claimed 30,000 lives in the nineteenth-century.[7] London therefore looked simultaneously towards the future and back into its heritage for a solution.

The mythological origins of London/Londinium are traced to A.D. 43 when Brutus of Troy captured England for the Roman Empire after a battle with Gog and Magog. Although the etymological origin of the word “London” remains under debate, water is a prominent figure in many theories. Richard Coates believes London is derived from the Celtic word (p)lowonida, meaning a river too wide to ford-a reference to the River Thames. Others believe London is a derivation of Llyn Did, meaning “lake fort” in Celtic.[8] Vitruvius provides evidence of an early sewer system in Rome called the cloaca maxima, lending evidence that England likely had knowledge underground waste systems due to the Roman occupation.

Preliminary research indicated the existence of just two manholes inside Westminster Abbey and that the ancient River Tyburn flowed beneath. In actuality, 15 manholes are visible to tourists inside Westminster Abbey with a total of 53 floor openings of various types. This article will be a catalog of the many manhole companies that have worked inside the Abbey, including Thomas Crapper, T&W Farmiloe, Burn Brothers and Burt & Potts. We even came across a wooden manhole, likely dating back two centuries.

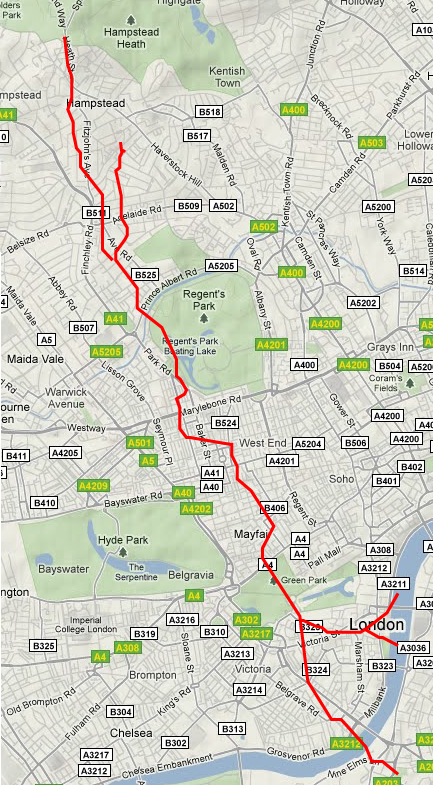

The Tyburn River begins in Hampstead, flows through Regent’s Park and St. James Park, and empties into the Thames. The river once branched to form the island of Thorney, upon which Westminster Abbey was built.[9] The river was first used as a source of fresh water and later as a de-facto sewer. In fact, the first record of an underground sewer and water system in London was under Westminster, built during the reign of Henry II.[10] While the Londonist has reported on the path of the Tyburn from a pedestrian angle, guerilla urban explorers such as Steve Duncan have followed the Tyburn River underground. He writes, “Today, the Tyburn is a sewer flowing through a brick tunnel. Officially titled the King’s Scholars’ Pond Sewer, it’s about three meters in diameter when it passes underneath Buckingham Palace. Walking through it we saw many side channels-some go only a short distance to manhole shafts, some connect to side-street sewer lines. There are also consistent tap-ins (individual sewer pipe outlets) from buildings built above the tunnel.” [11]

Map superimposing the path of the ancient Tyburn River onto a current map of London (by the author using Google Maps & strangemaps.wordpress.com)

Author Andrew Duncan recounts the history of King’s Scholars’ Pond Sewer in a book entitled Secret London. Kings’ Scholars’ Passage is a smelly road whose name derives from King’s Scholars’ Pond, into which the Tyburn used to flow. Duncan writes, “The King’s Scholars themselves were schoolboys at nearby Westminster School. When the Tyburn was covered over, this section was christened King’s Scholars’ Pond Sewer.” [12] Thus, the Tyburn and Westminster Abbey are linked both physically and etymologically to each other.