Play Vintage Games at the Red Hook Pinball Museum

Explore the museum's collection of meticulously restored vintage machines from as early as the 1800s!

We attended a tour of Fort Washington Park with David Freeland, author of Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville, who, having recently moved to Washington Heights, decided to explore his new neighborhood to see what lost treasures he could find. He came across a collection of relics scattered throughout Fort Washington Park which laid the basis for his tour.

The remnants of Paterno’s Castle in the foreground:

The remnants of Paterno’s Castle in the foreground:

The tour began on the corner of Fort Washington Avenue and 181st Street with a brief history of Revolutionary New York. The fate of the colonists was bleak and a series of forts had been constructed along the New York and New Jersey Palisades. Fort Washington, which lent its name to the park, was located a couple of blocks north from where we stood. Today, Bennett Park is located on the site of the fort. However, the story of the fort itself was merely a distraction to treasures we had waiting for us inside of the park. On our way to the park, our group passed the turreted retaining wall of Castle Village, one of the only remnants of Paterno’s Castle (pictured above).

An 1840s railroad bridge:

An 1840s railroad bridge:

As soon as we entered the park, we crossed over a railroad bridge built in the 1840s by the New York Central Railroad. The railroad was the first to cross into Manhattan. After crossing the bridge, we found ourselves on Sunset Lane, the colonial version of lover’s lane. It took a bit of imagination to picture our founding fathers arm in arm walking alongside their lovers down that very path.

The now paved Sunset Lane:

The now paved Sunset Lane:

Fort Washington Park exists today due to the tireless work of Andrew Haswell Green and his American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society. Nineteenth-century preservation societies viewed the preservation of history and the protection of nature as intertwined. For them, some of the most scenic sites were also the locations of the most turbulent events and therefore would be all the more valuable to future generations. Green was interested in preserving Fort Washington Park because of the unspoiled views it provided, because it was the site of a Revolutionary War fort, because it contained remnants from its American Indian inhabitants, and because possessed the largest collection of tulip trees on the Island of Manhattan.

Unfortunately today, there only only a couple of remaining tulip trees in the park and almost no American Indian relics left, which were still common to find as late at the 1920s. However, not all was lost.

David Freeland standing on Ceder Point:

David Freeland standing on Ceder Point:

Making sure not to slip on the rocks, and land in the Hudson River, we found ourselves at Ceder Point. Green and other nineteenth-century preservationists stood at Ceder Point over a century ago dreaming that future generations would still be able to take in the views of the sparkling Hudson River and the verdant Palisades from that very spot.

The view from Ceder Point:

The view from Ceder Point:

We passed under the tower of the George Washington Bridge on our way further into the park. Fort Washington Park is a patchwork park. Many of its sections are not easily accessible. From the train tracks, to the George Washington Bridge, to the Henry Hudson Parkway, each new threat that encroached upon the park had the potential to do more damage than ultimately occurred. As a result, the park exists today and many of the relics we observed on our tour were merely forgotten as another piece of the park was hidden away.

Jeffery’s Hook, which is most well known for the little red lighthouse, was the site of a gun battery during the Revolutionary War. The original promontory that gave its name to the Hook is no longer visible due to the work of Robert Moses who evened out the coastline with landfill.

Chevaux de frise are obstacles composed of barbed wire or spikes attached to wooden frames, used to block enemy advancement. Under the direction of General Israel Putnum, American ships were sunk in a line across the Hudson River between Fort Washington in Manhattan and Fort Lee in New Jersey to stop the British advancement up the Hudson. In order to sink the ships they first had to be moored and weighted. To our surprise, David pointed out the hooks that were used to moor those ships in 1776:

Jeffery’s Hook was chosen as the site of the chevaux de frise because it was the shortest point in the River. Unfortunately the barricade didn’t work and the British ships continued North up the Hudson River. It is likely that five or six of the ships are still sitting in the Hudson River, waiting for an intrepid team of divers to find them.

Our ascent into the depths of Fort Washington Park

Our ascent into the depths of Fort Washington Park

We ascended into the trees, continuing literally off the beaten path to find the highlight of our tour, the last original man-made Revolutionary War fortification visible in Manhattan. David rediscovered this lost piece of history in an 1898 walking tour created by the New York City Club. Following their directions, to his great disappointment, he came up empty handed. Retracing his steps, David realized he had not proceeded the 100 feet as directed in his guide. On his second attempt David discovered his prize:

The redoubt (fort) and Daughters of the American Revolution monument

The redoubt (fort) and Daughters of the American Revolution monument

Fort Washington had been constructed to stop British ships from sailing up the Hudson River. Despite this mandate, the Fort’s munitions were not powerful enough to reach the British ships. As a result, this redoubt was constructed in 1776 to supplement Fort Washington. The redoubt was designed by Felix Imbert, a French volunteer in the American Army, and constructed by Malcom’s Corps, a Scottish unit in the Army.

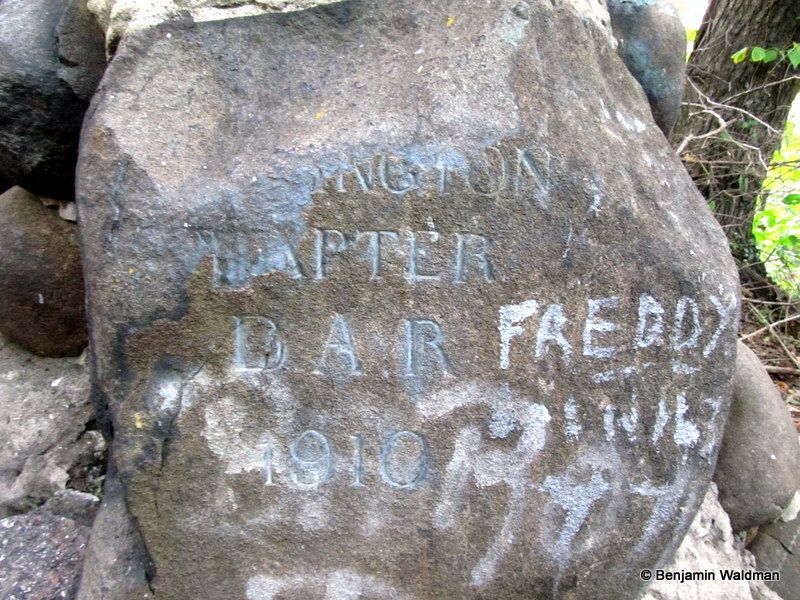

The presently defaced monument designed by Reginald Pelham Bolton:

The presently defaced monument designed by Reginald Pelham Bolton:

On November 16th, 1910 the Fort Washington Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution commemorated the 134th anniversary of the Battle of Fort Washington with the dedication of this monument. The DAR selected the date not to commemorate “either a victory or a defeat but to and show respect to those who in the darkest days of the Revolution fought so willingly and so valiantly for that which we all enjoy to day freedom and the protection of the Red White and Blue on that sacred ground.”

We forgot we were in Manhattan as we avoided thorn bushes and low lying trees:

To reach our next destination, we had to brave the thorn bushes and brush that covered our path. After climbing out of the underbrush we arrived on a promontory which provided a majestic view of New Jersey. Some of the rocks upon which we stood had mysterious metal bolts in them, and one, had a circle cut out of its center.

We learned, to our great surprise, that we were standing on the site of the first telegraph pole to connect New York and New Jersey. The bolts were used to secure the pole, whose construction was personally supervised by Samuel F. B. Morse, and the circle, which now has plants growing in it, was the place where the pole was erected. The telegraph pole was constructed in the late 1840s, but likely had a short lifespan. By the 1890s, no one quite remembered where the telegraph had been situated and there was speculation that this hole was of American Indian origin.

It is likely that these stone structures were built as either oven or grills. They were used by girl scout campers as early as the 1950s. However, their original use still remains a mystery. It is possible they were built by either the Civilian Conservation Corps or the workers who built the George Washington Bridge. A third possibility raised on the tour was that they served an ancient religious purpose used to celebrate the solstice. Unfortunately, we were not able to test this hypothesis on the tour.

One of the mysterious stone ovens:

One of the mysterious stone ovens:

If you are feeling adventurous and would like to retrace part of the tour, David provided directions in an article he wrote for AM New York.

Subscribe to our newsletter