Is Brownsville Brooklyn””long regarded as one of New York’s most troubled neighborhoods””ready for its comeback? There are some hopeful signs. The once-gorgeous Loew’s Pitkin Theatre, which debuted in 1929 and closed in the late 1960s, has undergone a $43 million renovation by Poko Partners, reopening with an Ascend charter school on the top floors and retail on the ground floor.

Pitkin Avenue itself, Brownsville’s crucial commercial corridor, has a revitalized Business Improvement District, headed by lifetime Brooklynite Daniel Murphy. A handsome 12-unit condo building developed by Habitat for Humanity welcomed its new owners in April. The percentage of students performing at grade level in reading and math is increasing, allowing StreetEasy‘s ads for modest houses to confidently stress the “transformed public school system.”

And why not? Geographically, Brownsville is the next in line to receive the youngsters and members of the creative class (to use Richard Florida’s term) that helped pull Bushwick up from the economic devastation wrought by the arson and riots of 1977. If Bushwick, Brooklyn (despite high crime) can attract investment and income diversity then so, surely, can Brownsville. Indeed, the L train””which cuts in a straight line across Manhattan’s 14th Street, plunges under the East River, and emerges in Williamsburg-Greenpoint before rather jauntily swerving through Bushwick””shows the way.

Rosanne Haggerty, an internationally renowned expert in housing and social issues who is now the president of Community Solutions, calls the L the “gentrification train,” which can bring income diversity to Brownsville while providing its residents with access to jobs. Also served by the IRT’s 3 line, Brownsville is a prime candidate for transit-oriented development. After all, as NYU’s Furman Center points out, over 85% of Brownsville residents live within a half mile of a subway or rail entrance. Haggerty has a plan, partly inspired by Jane Jacobs’s ideas in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, for how to harness the forces of gentrification, attracting far better retail and services, without displacing any residents or demolishing any housing units.

Can this work? Many New Yorkers, especially those with roots in Brownsville, would like to see the neighborhood do well. In its comeback journey, Brownsville’s vivid history is a potential asset.

A Neighborhood of Strivers

“Brownsville has always been a neighborhood of strivers,” says Daniel Murphy. “People want their children to do better than they did.” In his memoir of New York, A Walker in the City, the writer Alfred Kazin recalled the pressure of his upbringing in Brownsville, which in the early 20th century was a Jewish neighborhood known for radical politics. “It was not for myself alone that I was expected to shine,” wrote Kazin, “but for [my parents]””to redeem the constant anxiety of their existence. . . . Anything less than absolute perfection in school always suggested to my mind that I might fall out of the daily race, be kept back in the working class forever.”

Kazin was especially fearful of falling into what he called the “criminal class,” because Brownsville, Brooklyn was home to Murder, Inc. and its mobsters, including Lucky Luciano and Bugsy Siegel. Nonetheless, Brownsville also produced celebrated New Yorkers, including composer Aaron Copland, comedian Danny Kaye, television host Larry King, public intellectual Norman Podhoretz, and historian Howard Zinn. Most of these achievers had been raised in the tenement housing stock built in the late 19th century and demolished in the 20th””often to make way for federally funded public housing, built for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

Jewish households left Brownsville in large numbers after World War II. In the 1960s the neighborhood, which had become mainly African-American, remained poor and crime stayed high. Brownsville was seared by a damaging riot in September 1967, which drove even more merchants out of business, followed a year later by the devastating Ocean Hill-Brownsville teachers’ strike, which seriously frayed the relationship between New York’s black and Jewish communities, says historian Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation.

The ’60s had been bad for Brownsville, and the ’70s weren’t much better. New York City’s near bankruptcy in 1975 followed by years of fiscal crisis, raised taxes, and depressed city services, left Brownsville isolated and pretty much abandoned to its own resources. Violent crime became so endemic that architect Oscar Newman, author of Defensible Space, based his argument that high-rise buildings were inherently unsafe on the daily crime in the Brownsville and Van Dyke projects. Coverage in mainstream media over the next few decades focused on little other than crime. The occasional good-news piece was usually about one of Brownsville’s gifted athletes””Mike Tyson, Riddick Bowe, Shannon Briggs, Willie Randolph””or entertainers””Masta Ace, M.O.P., and The RZA.

True to its earlier heritage, Brownsville continues to produce writers. Music critic and filmmaker Nelson George, for example, whose family had moved to New York from Virginia, says they were part of the wave of black and Latino immigrants from the South and from Puerto Rico. The neighborhood was still sufficiently Jewish and Italian for George to grow up eating knishes, going to bar mitzvahs, and consuming Italian food. His mother was upwardly mobile and determined to go to college to become a teacher while bringing up George in the Tilden projects, “where the threat of violence” swept up “out of the ground.”

Playwright and performer Elaine Del Valle, author of Brownsville Bred, also grew up in the projects, in her case, the Langston Hughes Houses, which she recalls as the “toughest buildings in Brownsville.” She set herself firmly on the upward path by getting admitted to Brooklyn Technical High School, thanks to her teachers at PS 284, who “were kind, compassionate, empathetic, ready to help us succeed, to teach us pride in who we are””even though everybody outside looks at you as if where you live is the worst place on earth.”

Tough Buildings

Brownsville has the highest concentration of public housing projects in New York””and thus probably in the country. The projects’ design””which almost no one defends today””developed from the ideas of eminent mid-20th century planners, dubbed “Decentrists” by Jane Jacobs, who borrowed the term from housing activists. Decentrists thought urban streets were destructive environments for human beings, and recommended turning housing inward toward sheltered greens, away from the street. The basic unit of design would be the block, especially the superblock. Commerce would be segregated from residences and parks, and limited according to scientific calculations of what residents needed. By design the projects became what Jacobs called “self-isolating.”

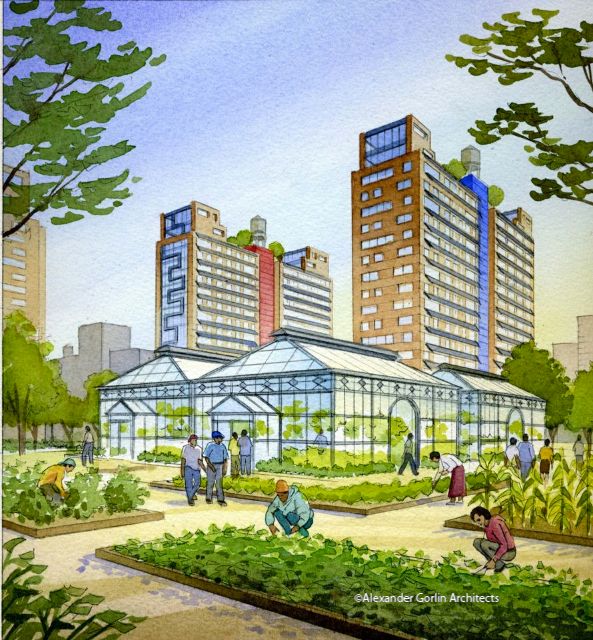

Brownsville’s existing site, as rendered by Alexander Gorlin Architects, shows the inward-looking, self-isolating design so familiar in public housing.

The Decentrists’ ideas are starkly laid out in Brownsville, whose immense projects are built on superblocks stripped of retail, making a mockery of Jacobs’s description of urban neighborhoods as “delicate, teeming ecosystems.” Ironically, despite their seeming density, the projects are inefficiently built in contemporary terms, with large amounts of deserted open space””in other words, space that offers an opportunity to develop something better without displacing any residents. Indeed, architect Alexander Gorlin estimates that Brownsville has some 2 million square feet in unused air rights. Fred Harris, NYCHA’s Executive Vice President for Development, is supportive, noting that “the forms of our buildings that look nice on a map often feel insecure and exposed at ground level. We’d like to see our streets lined with stores, welcoming entrances off sidewalks, maybe even a new residential tower close to the subway station, which might be a candidate for housing for moderate-income households.”

Indeed, in his well-received book, Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto, historian Wendell Pritchett points out that while many employed, moderate-income residents left in the 1970s, many stayed, in part because they moved into the Nehemiah Houses, constructed by the East Brooklyn Churches. In other words, the demand for moderate-income housing, such as that identified by Harris, remains strong in Brownsville.

Rosanne Haggerty hopes to start with a particular spot””Livonia and Rockaway, an entrance to the Tilden Houses that now looks bleak and empty, except for some garbage bags and parked cars.

The very fact that Haggerty has a plan brings hope to people struggling to turn Brownsville around. Her efforts in other neighborhoods””Times Square, for example””have been so successful that people new to New York often regard the bad old days as urban myths. They have trouble believing that Times Square hosted heroin addicts, street prostitutes, and vicious violent felons. Haggerty’s ability to look upon even the most troubled person as a human being worthy of respect combined with her acute analysis of the social problems associated with living on the street helped her formulate a remarkably effective strategic approach to combating homelessness. (As a “pioneer in the development of supportive housing and other research-based practices that end homelessness,” Haggerty received the Rockefeller Foundation‘s 2012 Jane Jacobs Medal, administered by the Municipal Art Society. The award cites Common Ground, which she founded in 1990, for providing “innovative shelters for homeless adults” through a “network of well-designed, affordable apartments, which link people to the services they need to maintain their housing, restore their health, and regain their economic independence.”)

But in her Common Ground days she observed that many families who applied to live at city shelters had come from a few neighborhoods, suggesting the need for place-based solutions. One neighborhood was Brownsville. “Follow the data,” she says, “and you’ll see concentrated problems. You’ll find that a large percentage of people who are homeless had been in the child welfare system. At the same time Brownsville has huge clusters of young men who have never worked. Many dropped out of high school. Brownsville also has high levels of obesity and diabetes, indicating that it matters how a neighborhood gets its food, it matters what people eat.” Thus Gorlin’s renderings of how public housing might be reconfigured include reestablishing the street grid, as Jane Jacobs suggested, and also providing community and rooftop gardens.

Haggerty’s approach involves working with talented people from all fields””health, education, justice, housing, parks, business””“chipping away at the problems, starting to produce change.” To move the plan forward the Brownsville Partnership will build on its remarkable range of partners to hold community discussions and conferences. Reflecting on his life in old age Alfred Kazin commented, “Brownsville is the road which every other road in my life has had to cross.” Brownsville is itself now at a crossroads. The future won’t be easy, but Brownsville’s energy and aspirations, Haggerty’s ideas, Gorlin’s renderings, and NYCHA’s receptivity to reintegrating its projects into city life bode well.