New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

Belfast is the capital city of Northern Ireland; home to 286,000 inhabitants (650,000 in the greater Metropolitan area). It is the region’s economic powerhouse but remains a deeply divided city. An industrial city, Belfast was once given the title ‘Linenopolis’ as it was the largest producer of linen in the world during much of the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, the most famous ship of them all was built in Belfast, the Titanic.

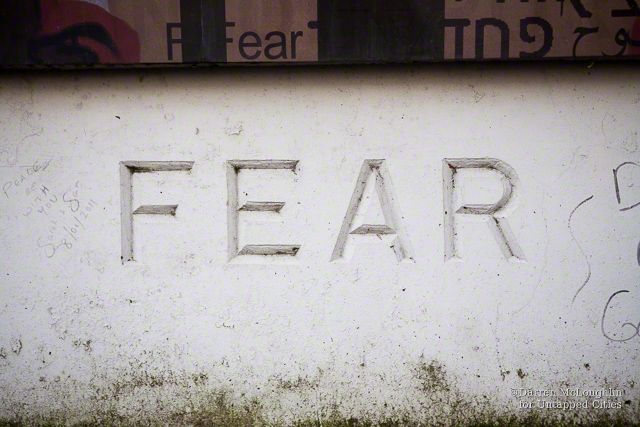

There is no doubt that Belfast has come a long way from the height of The Troubles, the ethno-political conflict that lasted from 1969 to the mid-1990s and which plagued Northern Ireland costing over 3,500 lives. Today Belfast City is a bustling centre of trade and commerce with a thriving music, arts and café scene. Still, there are 99 barriers that prevent movement between adjoining districts in the city.

Included in these barriers are the “peace lines” or walls crossing the city keeping neighboring Protestants and Catholics apart. Approximately one third of these walls have been erected since the paramilitary ceasefires of the mid-1990s that led to the Good Friday Agreement – a political settlement chaired by US Senator George Mitchell between the Irish and British governments and the opposing paramilitary groups that had been engaged in conflict for almost 30 years.

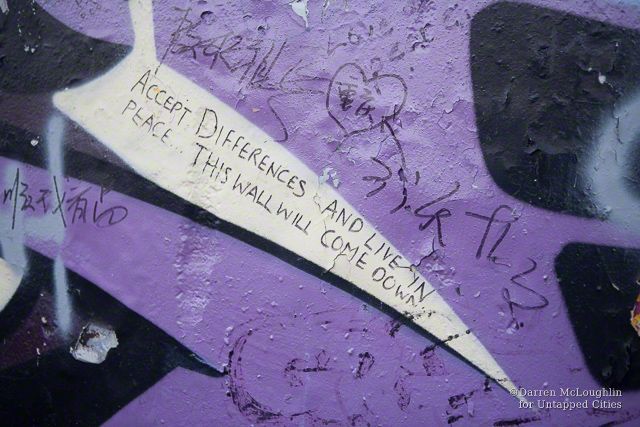

With a recent deal agreed between parties in the Northern Ireland Assembly (the regional government) all of these walls and other barriers are scheduled to be taken down within the next 10 years. Funding is available to local community groups to encourage this to happen.

In the west of the city, the Falls Road and the Shankill Road come close together and many of their link roads were, occasionally still are “flashpoint” areas where trouble can erupt spontaneously. During The Troubles some of these roads were used by gangs to facilitate bombings in neighboring communities or to abduct and kill members of the public, some simply chosen on the basis of which direction they were walking in. Because of this historical legacy and the feeling of security that the walls give to those that live near them, they remain in place and many of the roads are closed at night or during times of heightened tension.

The longest of the peace lines, Cupar Way divided the two communities, Protestants on the Shankill and Catholics on the Falls. It was built in 1969 at the start of The Troubles and is composed of 4 metres of concrete wall with 3 metres of metal sheeting topped off by a further 6 metres of mesh fence. That’s 13 metres or nearly 45 feet high and it has been in place for longer than the Berlin Wall was in existence.

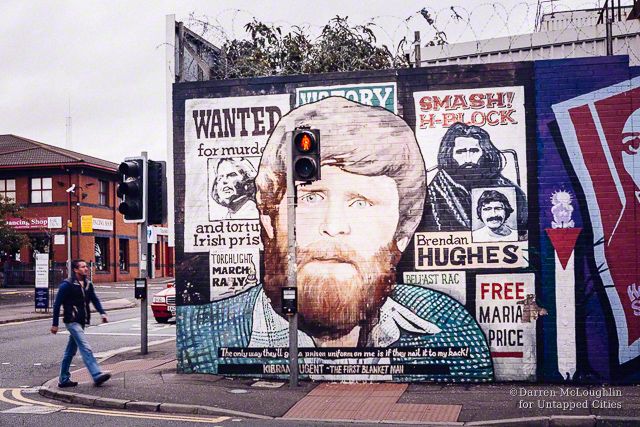

Encouragingly there is a growing development of cross-community initiatives that aim to bring people on both sides of the wall together and this are is now home to an vibrant mix of political murals, graffiti and commissioned public art.

Although not on the peace line itself, the “International Wall” sits close to Cupar Way on the Falls side and includes some murals on political themes, environmental issues and features famous world figures. Importantly this wall still has a mural painted by two artists based on Picasso’s Guernica. One a Catholic, the other a Protestant these two artists come from different traditions, from different sides of the peace walls and it was an important step in creating the possibility for more collaborations and cross-community initiatives.

Banquet by Rita Duffy

Rita Duffy, a Catholic Belfast woman was chosen by the Shankill Women’s Centre to create a mural celebrating the centenary of International Women’s Day in 2011. Featuring local women in various roles, Banquet, a large-scale photographic work was funded by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. Above the piece some of the houses on the Falls Road side of the wall can be seen behind the wire mesh fencing.

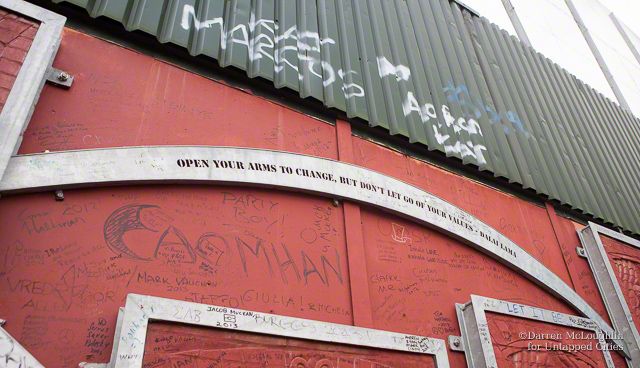

The Arts Council, the statutory body responsible for promoting the arts in Northern Ireland have funded much of the public artwork on Cupar Way under their Building Peace through the Arts – Re-Imaging Communities program. The program supports community groups in Belfast and across the six counties of Northern Ireland as well as the border counties of the Republic of Ireland “to tackle sectarianism and racism by engaging local people with artists and the development of public art.” The program seeks to use public art to encourage communities to integrate while allowing them to express their own identity, perhaps best summed up by a quotation featured on the wall by the Dalai Lama during a visit to Belfast “Open your arms to change, but don’t let go of your values”.

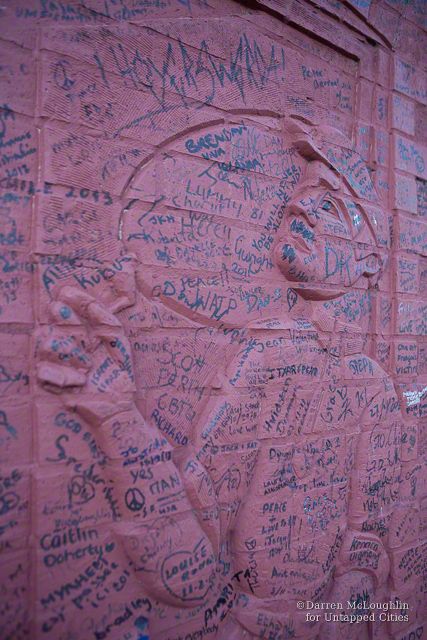

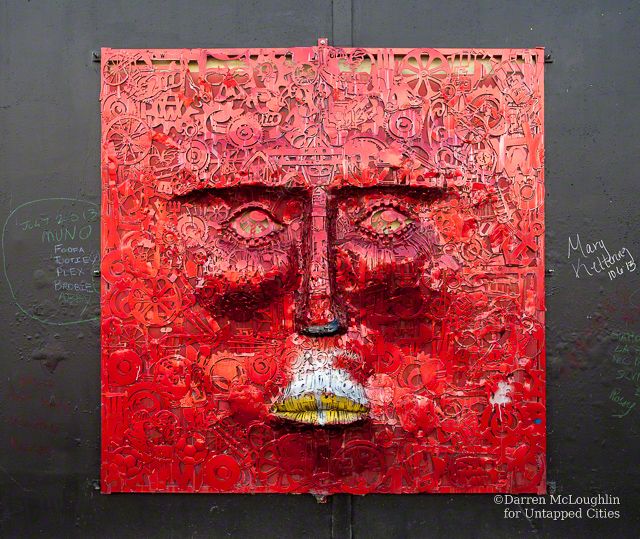

The Face by artist Kevin Killen, is part of the “If Walls Could Talk” project and was created in collaboration with young people from the area and is comprised of elements representing Belfast’s heritage and culture.

Graffiti can also be found in abundance on the Cupar Way peace wall. At times the colour leaping off the concrete panels as the road stretches into the distance is attractive, juxtaposed against the high mesh fencing erected to stop objects being thrown over. Local, Irish, British and international artists have all put their stamp on the wall.

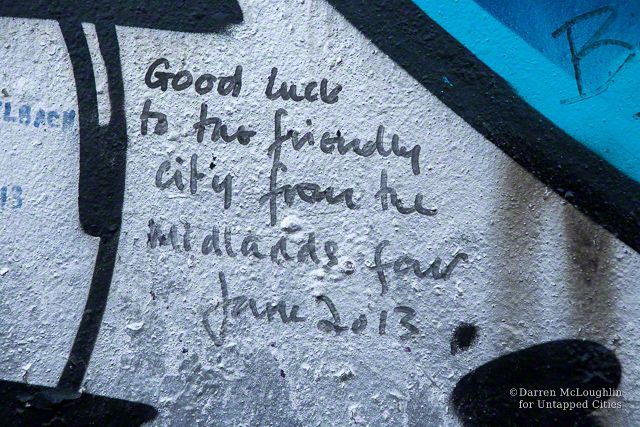

Today on Cupar Way it’s rare to meet a local out walking, yet many tourists stop off during their Black Taxi Tours to see the wall, its murals and street art. Thousands upon thousands of messages are scrawled onto every inch of the wall from an estimated 500,000 annual overseas visitors. Many of these visitors are attracted to Belfast and its peace walls by recent reviews from international media outlets citing Belfast as a must-see destination. Some of the messages are just dates and names but all along the wall are short messages of peace and hope.

If the Cupar Way peace wall should come down it would be fair to say that the art and artists working here, encouraged and fostered by the local communities will have played a role in facilitating the transition from a divided city to a progressive, integrated one. It’s all good.

Read more about street art in Ireland, in “The Evolution of Dublin’s Street Art Scene.” Get in touch with the author @travelimages.

Subscribe to our newsletter