Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Deep below Grand Central Terminal, there’s a hidden power station known as M42 that does not appear on a single map or blueprint. In fact, the very existence of the M42 basement was only acknowledged in the late 1980s and its exact location is still not public information. Nonetheless, unpublicized special tours have allowed the curious to head down there in the last five years or so. We can’t share all the details of how we landed on the coveted visit, but we were given the opportunity to explore this and other off-limits places in Grand Central Terminal recently – and took photographs.

Most famously, the M42 basement (also known as Substation 1T and 1L) is said to have played an important, clandestine role in World War II. In a story long told by Daniel Brucker, the former docent-in-chief at Grand Central, the original converters, which are no longer in operation, powered much of the New York Central Railroad and were a target for German spies who wanted to sabotage rail movement on the East Coast. Brucker would say that the M42 basement was so secret that you risked being shot on-site if you went down there.

While there were spies in America focused on destroying infrastructure, there is no contemporary evidence as of yet that Grand Central, or the M42 basement specifically, was a target. In the book Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America, writer Sam Roberts offers that Grand Central could have been a target but as I Ride the Harlem Line documents, neither the reports from MI5 or first-hand accounts by the spy ring’s own members mention it.

Historically, M42 was part of the shift from steam-powered locomotives to electrified rail, spurred on by a horrific accident in the Park Avenue tunnel in 1902. Steam blocked sight lines in the tunnel out of Grand Central Station (the previous incarnation of the current terminal) and an express train from White Plains and a commuter train collided under 56th Street, becoming the worst train accident in New York City up to that point. Steam trains were banned in Manhattan starting in 1908 and the New York Central set out to find an alternative.

William Wilgus, the chief engineer of the New York Central, worked with General Electric to design the new rail system, which used 600-volt direct current. As Thomas J. Blalock, a development engineer at the General Electric High-Voltage Engineering Laboratory so thoroughly details in IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, the voltage was “distributed via third rails with one track rail serving as the return. Eventually, this power system was extended through the Bronx and into Westchester County to the north.”

Third rail power was produced by two different steam substations – one on Park Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets and one in Yonkers. The latter, the Glenwood Power Station, still stands today but following years of abandonment and much urban exploration is staged to be redeveloped. The Park Avenue power station was later demolished, both because residents had come to see it as an “eyesore” and because a sale of the increasingly valuable land and air rights was needed to fund the new Grand Central Terminal. You will recognize this plot of land today as the site of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

In 1929, the power for the New York Central was moved underground into a new space, which was formerly the steam plant beneath Grand Central. Equipment from the Park Avenue substation was lowered via a hatch in the floor of the former substation onto flatbed trains, and then down another hatch. One of the tracks used on the upper level train yard is the famous Track 61, used by Franklin Delano Roosevelt to move in and out of the Waldorf-Astoria.

As Blalock explains, a “total of 850 tons of electrical equipment was eventually moved in this manner. A new 35-ton overhead traveling crane was used to reassemble the rotary converters and other equipment in Substation 1T.” A massive battery was also moved underground through a different method. All of this was done without disrupting train traffic and was actually completed ahead of schedule.

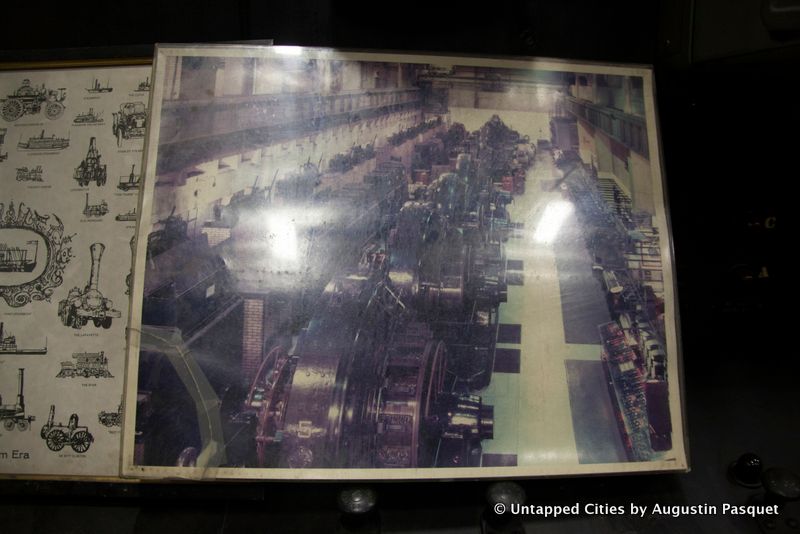

Here, in the M42 Basement, high voltage alternating current was transformed into direct current. There were ten rotary convertors here, as you can see on the vintage photograph that is on display in the basement room today:

The M42 basement is accessed by keycard through a nondescript door somewhere in Grand Central Terminal. You head down levels and levels of staircases, until you can reach out and touch the original Manhattan Schist rock.

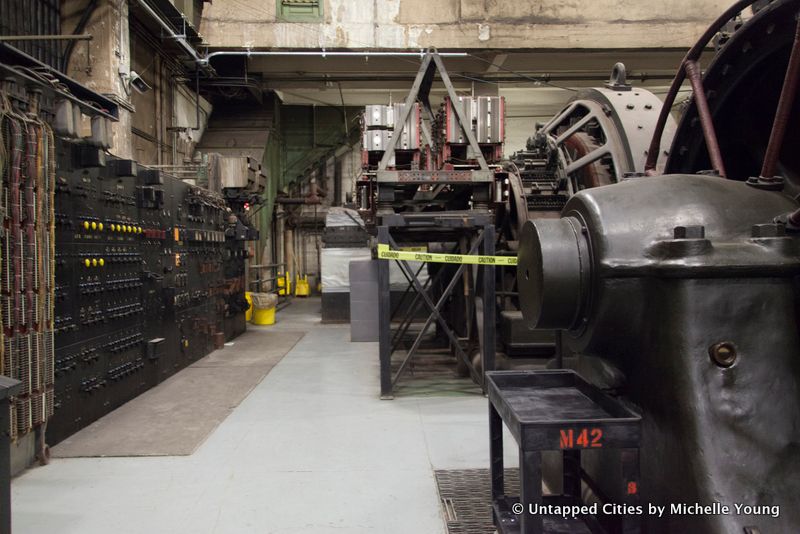

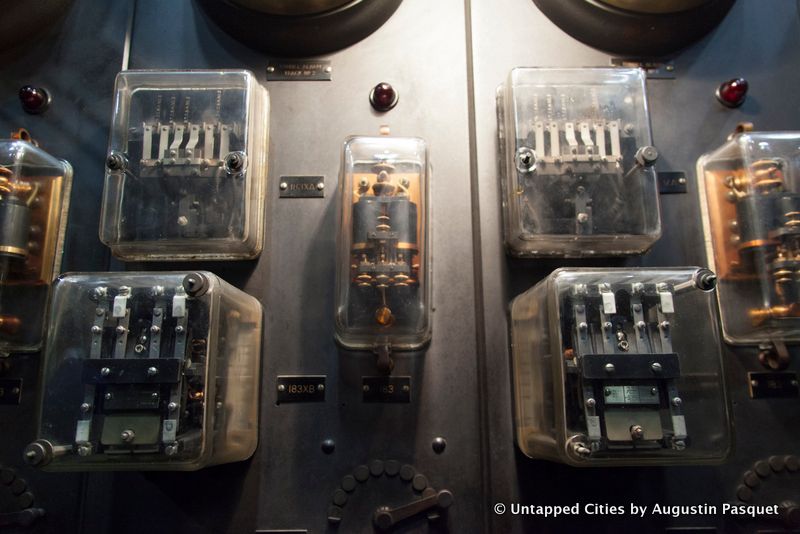

The numerous rotary converters in M42 were later replaced by rows of more modern equipment, which still operate today:

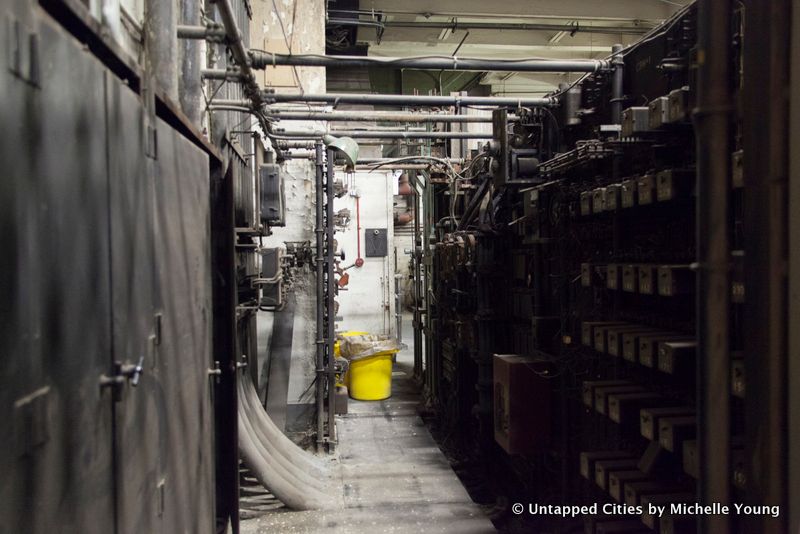

But a few have been left deliberately for posterity:

A Weston ammeter that measured the current in circuits:

A cart labeled M42:

The first thing you’ll see when you enter M42 is the back of the switchboards on the left:

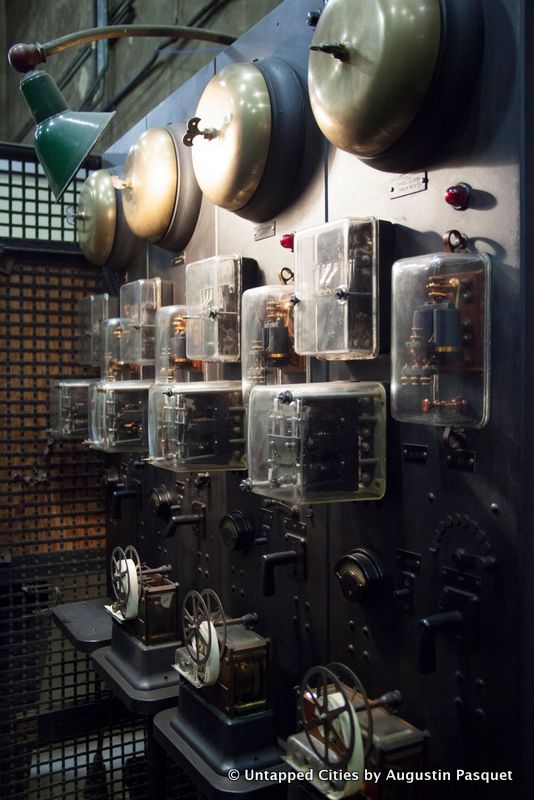

Front of the switchboards:

Numerous voltage meters:

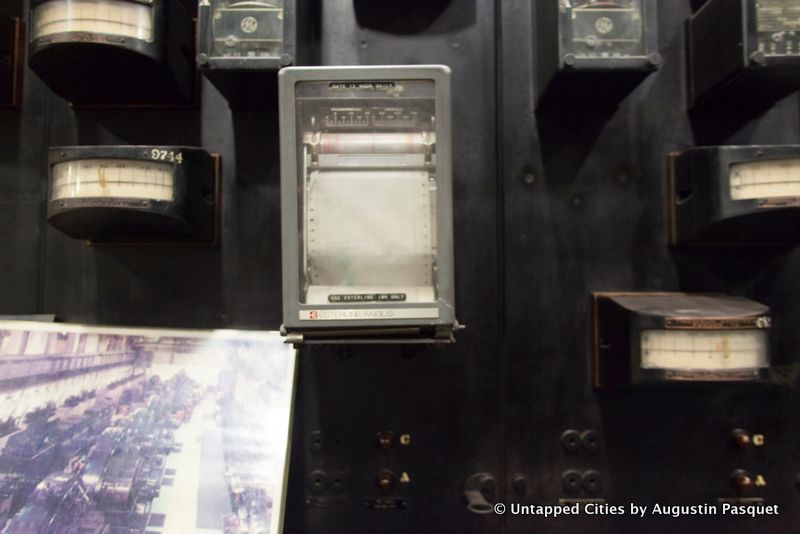

Below are notifications from Substation 1B, which is an adjoining room and has been in operation since 1927 to power the Graybar Building and the Commodore Hotel, all within the Grand Central Terminal City complex:

More equipment:

View from the old equipment area of M42 looking towards newer equipment and office:

Photo of Untapped Cities contributors, which include architects, urban planners and photographers:

Next, discover more Secrets of Grand Central Terminal and join us for an upcoming tour of the terminal’s secrets (but the basement level is not available for public tours):

Subscribe to our newsletter