Preview The Orchid Show: Mr. Flower Fantastic's Concrete Jungle

Get a sneak peek of the New York Botanical Garden's exquisite new exhibition!

Last night, 800 people in person (and 1,400 people and counting through Facebook live) attended The Summit for the Future of Penn Station at Cooper Union, an event produced by Untapped Cities in partnership with the Museum of the City of New York. This discussion, moderated by Jose Martinez, transit reporter for NY1 about the challenges and potentials of the future Penn Station featured Susan Chin, President of the Design Trust for Public Space; Robert Eisenstat, Chief Architect at the Port Authority of NY & NJ; Gina Pollara, President of the Municipal Arts Society; John Schettino, Designer of The New York Penn Station Atlas; Tom Wright, President of Regional Plan Association.

Introductory remarks were given by Michelle Young, Founder of Untapped Cities and Adjunct Professor of Architecture at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and Whitney W. Donhauser, Ronay Menschel Director and President, Museum of the City of New York.

Young spoke of the importance of a design that involves the input of New Yorkers. “New Yorkers were certainly not part of the decision to demolish the original station so how can we, the public, make our voice heard in the developments to come now?” Sharing about the activism of Untapped Cities about Penn Station and its popular Tour of the Remnants of Penn Station, she contended, “It is our belief that a new Penn Station should be conceived as a great civic public space that can persevere for centuries, that it should be designed with the input of the public, and that it should serve not only the functional needs of a growing New York City but also be an example of what this city can build, together.”

Donhauser brought for the competing visions of Penn Station in the mind of New Yorkers, saying “Penn Station lies at the intersection of New Yorkers’ understanding of style and substance, with the old building recalling visions of civic beauty and the current transportation hub causing modern day commuting nightmares. Few subjects mean so much to our city from both an aesthetic and a practical perspective.”

Here are 10 fun facts about the current Penn Station, many of which we learned at last night’s event.

The urgency for a new Penn Station is very real. Built for 200,000 commuters, today, 650,000 people go through Penn Station each day, more than the daily passengers for all three major New York City-area airports combined. As John Schettino of The New York Penn Station Atlas so effectively pointed out in his presentation, this number is also larger than many of the major cities of the United States: Atlanta with a population of 463,878, Miami with 441,003, and Cleveland with 338,072.

The official number of visitors to Grand Central Terminal is 750,000, but that includes the many tourists and shoppers that take in the sights there. Penn Station, because of its less than desirable interior, is mostly packed with commuters, which makes a future Penn Station that truly serves its users more important than ever.

Last night, a trailer about the Untapped Cities tour The Remnants of Penn Station was also shown, explaining the mission behind the tours and its origin as a Kickstarter gift for the off-Broadway play, The Eternal Space. Justin Rivers, the playwright of the play, gives the tours, showing that there is still a “still-beating heart of the old one.” On the tour, we show you more than a dozen remnants of the original Penn Station hidden in plain sight inside the current station, and why they still persist. They range from small tiles and floor pieces to a full building that takes up half a block. The cast-iron waiting room partition above in the Long Island Railroad concourse was only discovered in the renovations of Penn Station in the 1990s, behind a walled off area.

Join us for an upcoming tour:

Tour of the Remnants of Penn Station

This remnant is considered the holy grail of remnants, out of sight to the public for decades in a storage closet near the Lost & Found and baggage area. These cast-iron track indicators once stood at the entrance of the boarding gates at Penn Station and were custom designed, according to Lorraine Diehl in The Late Great Pennsylvania Station, to”conform to the ornate fencing that enclosed the platform area.” We were able to locate a portion of that original fence in Penn Station, which is a visit on our tour.

The indicator would have had a number of the track number in the red portion on top. The 1 and the 7 numbers are part of a departure time that used to be displayed.

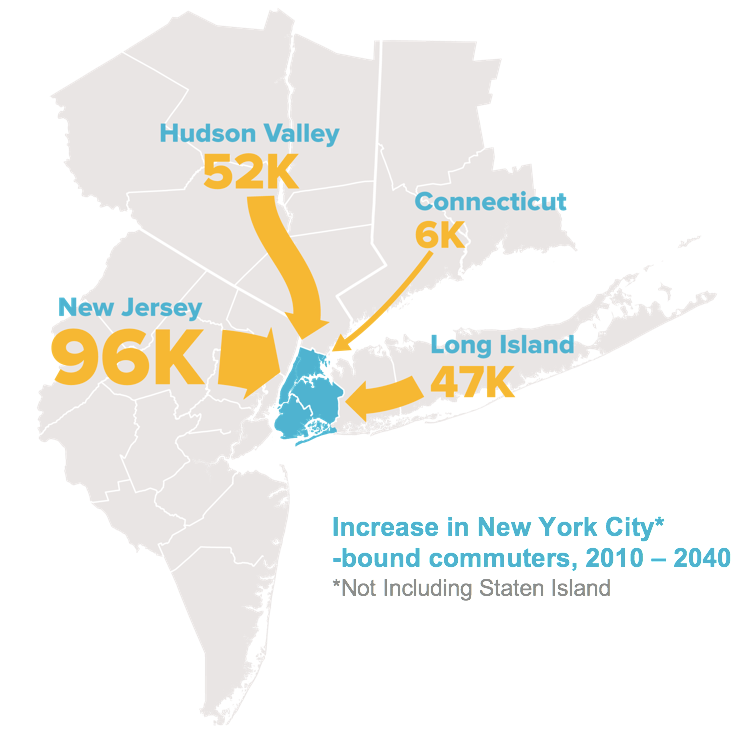

Graphic via Regional Plan Association

As Tom Wright, President of The Regional Plan Association, showed in his presentation last night, it is estimated that by 2040, 210,000 more commuters will come into New York City every day (not including Staten Island). 46%, of 96,000 of that increased is expected to come from New Jersey alone. And historically, 83% growth in Manhattan-bound commuters from 1990 to 2010 was driven predominantly by that state. This easily demonstrates the urgency of not only renovating Penn Station into a world class transit hub, but also increasing capacity for regional transportation.

As John Schettino pointed out, Penn Station is both congested and confusing, with congestion amplified because of confusion. He points out that each area of Penn Station is managed separately – Amtrak, Long Island Railroad, New Jersey Transit and the MTA subway system– with very little alignment between them, particularly in terms of wayfinding signage.

One of the ways we show our tour-goers how to tell where you in Penn Station is to look at the floors. Each part of the station has a different type of floor, depending on which transit agency area you’re in – marble for New Jersey Transit, the area most people agree is the nicest in the station, the granite-like tile in the Long Island Railroad area, and the massive blocks of tile in the Amtrak area, separated by silver joints. The cleaning crews of each also literally only go up to the line of their jurisdiction, conveniently noted by the change in floor pattern.

The Hilton Passageway gave access for commuters between Penn Station and the N/R/Q and B/D/F/M trains until the 1970s, when it was closed off due to security reasons. It was reputedly narrow and in a state of disrepair. Today, it is simply blocked off by bricks – you can see the original opening by the change in white bricks along the wall.

A remnant of the old Penn station

As John Schettino pointed out, the novice user of Penn Station, the tourists, regional travelers, those that may only come to Penn Station “once in their life,” are the people we should plan for because confused users turn into lost resources. Robert Previdi, former New York City transit planner told The Star-Ledger in 2013 that he estimates novice users to number 30,000 people per day. Even if we work from a conservative estimate and say that 1% of daily users are novices in Penn Station, that could be around 6,500 people using the 650,000 user number.

Using this conservative estimate, Schettino estimates that 43 weeks of time are lost per year dealing with confused users. He calculates this using 5000 people x 15 second queries = 20.83 hours per day. He also notes that some of the station’s security apparatus become dedicated to answer questions from lost commuters and that the indirect movement of confused users cause delays for the daily, experienced users and the occasional users.

Thus, even though the novice user is a small percentage of the total, “Novice impact is inverse to size of novice group,” says John, emphasizing the need to plan for this minority.

To the average New Yorker, Penn Station notorious for being quite possibly the most hated building in entire city. Not only is it difficult to maneuver around the throngs of people, but the station itself is a replacement of a much grander landmark. Despite these grievances, we urge you to pay attention to the signage and discover some great puns in Penn Station. (Or should we say, Pun Station?)

One of the locations you’ll discover on our Remnants of Penn Station tour is the original coal-fired power plant of the station, built as a mirror image using the same Tennessee granite as the lost Stanford White masterpiece. This building on 31st Street is just one of the many pieces (though this is certainly the largest remnant) scattered throughout the station area including eagles, railings, floor tiles and more.

Today, the power plant is a significant state of disrepair, with windows. As of 2003, it was reported by The New York Times that the building was used for “storage and backup systems.”

A rendering of Vishaan Chakrabarti’s plan. Image via Practice for Architecture and Urbanism

Instead of demolishing Madison Square Garden, as earlier plans to transform Penn Station had called for, Vishaan Chakrabarti, founder of the Practice for Architecture and Urbanism seeks to transform it into a “neighborhood gathering spot.” The proposal would eliminate the need to construct an entirely new building by utilizing Madison Square Garden’s stripped skeleton to make a glass pavilion; the venue would also be relocated to the west end of the Farley Building.

Join us for an upcoming tour of the Remnants of Penn Station:

Tour of the Remnants of Penn Station

View the Facebook livestream of the event here. Next, check out 5 Remnants of the Original Penn Station in NYC and see What Penn Station May Look like in 2020.

Subscribe to our newsletter