After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

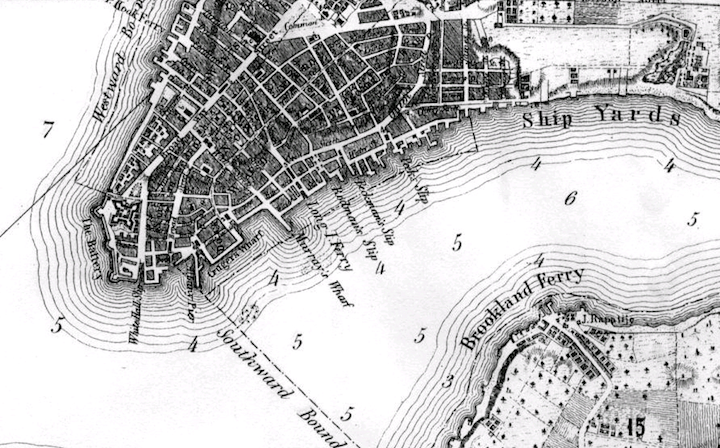

This 1766 map shows the some of the earliest known slips in what was then New Amsterdam, including Peck’s Slip, which once sheltered George Washington and his troops from the British Army.

Though you’d never know it nowadays, many of the long, narrow parks that cut into the Eastern edge of lower Manhattan and run almost all the way to the East River once served as some of the primary boat slips for old New York’s shipping enterprise nearly two hundred years ago.

Dating back to when the first Dutch immigrants populated what was then New Amsterdam, these slips actually formed some of the only non-man-made parts of the marshy East River waterfront. In what would have been typical fashion, the Dutch settlers actually built up the land on the shore when the tide went out. They created an extensive polder that became the easternmost coast of lower Manhattan, and left only the narrow slips as evidence of the ocean that at one time covered the whole waterfront.

These narrow landfills not surprisingly became somewhat ambiguous land, existing between urban territories, and have re-surfaced in our urban consciousness most recently as the site of contention between residents and a forthcoming high-rise development that will replace the local Pathmark store. Pike Slip was notably the first location of Pathmark in Manhattan but is slated to close before the end of the year (though the company retains the right of operation in the new development). Of particular concern is the access to affordable food for the neighborhood. Equally incongruous to the current social and built fabric is the presence of luxury developer Extell (the same developers as One57 in Midtown) on the property.

According to an 1825 publication called The Picture of New York, or The Stranger’s Guide to the Commercial Metropolis of the United States, written by E.M. Blunt, twelve slips were once in operation on the East River–although another publication from the same time period adds George, Catherine, and Charlotte Slips to Blunt’s list:

Most of these slips were eventually filled in by 1898, but only some of them remain distinguishable today, functioning as parks, public malls and roads. Pike Slip is by far the largest of these, but the other slips have an equally interesting history.

Peck’s Slip, for example, which occupies the area between present-day Water and South streets, served as an active docking place for boats until 1810, and even served as a temporary hideout for George Washington and his troops in April 1776 when they fled from the Battle of Long Island. Then, in 1838, the first steam-powered vessel to make a transatlantic voyage, the S.S. Great Western, docked in Peck’s Slip to the cheers of a quickly growing crowd of onlookers.

However, you might better recognize the space as the former parking lot for the Fulton Fish Market, which was moved to the Bronx in 2005. According to city Parks and Rec, construction on Pecks Slip Park will start in 2013. However, the area is already pretty active within the community; just last November, the first annual Peck Slip Pickle Festival took place at the New Amsterdam Market, further up the slip.

Catherine Slip, which you probably know as Catherine Slip Mall, located between Cherry Street and South Street, is named after Catherine Rutgers, after whom the New Jersey university is named. The only daughter of the wealthy Anna Bancker and Johannes De Peyster (who was appointed mayor in 1698), Catherine was part of one of the elite Dutch mercantile families that lived in lower Manhattan in the 1700s. Originally part of the Rutgers’ expansive land holdings, Catherine Slip became part of the city’s public holdings sometime around 1730, and in the late nineteenth century, after the little boat slip had been converted into a landfill as part of the city’s efforts to extend the edges of Manhattan, Catherine Slip served as a public market, providing an escape, albeit a small one, for the choked population of the squalid tenement buildings during that time.

Around that time, Catherine Market became famous for its Sunday morning eel market, frequented by traveling musicians, and the bizarre but popular “Dancing for Eels Contest,” in which the best dancer would win a live eel. (A blog called Knickerbocker Village has a great little slideshow about the custom.) Long after the city condemned the tenements and the market itself disappeared, the slip became one of the many public land holdings restored by the Works Progress Administration under Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939; workers planted trees and installed benches, reconstructing the park to serve as a central mall, which has lasted until present day, thanks to its maintenance by NYC Parks and Rec.

A stereoscopic view of Coenties Slip in 1876. Photo from the Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views, part of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs found at the New York Public Library system’s Steven A. Schwarzman building in midtown.

Of these former inlets, Coenties Slip saw the longest period of use as an actual shipping alley, and was the last of the slips to be filled in for use as a landfill in 1868. Its strange name is actually a contraction of the first names of the couple to whom it was dedicated, Conraet Ten Eyck and his wife Antje. While in its heyday, the little inlet became a favorite docking place for Canadian barges out of the Erie Canal, Coenties Slip (pronounced Koh-un-tees) also became well-known in the 1950s as home to a group of artists led by Robert Indiana (the man responsible for 6th Avenue’s “LOVE” sculpture), who made their studios in former sailmaking shops.

The narrow swath of land is now a historic pedestrian walkway which culminates in a small, round park that features a futuristic sculpture by artist Bryan Hunt. The sculpture, erected in 2006 as part of the Art Commission of NYC’s Percent for Arts Program, is a 20 foot tall stainless steel form resting upon a dome of cast glass that is called “Coenties Ship,” and is meant to “invoke buoyancy and nautical nuance poised for a future,” according to Hunt’s website. Located at Pearl Street near Water Street, Coenties Slip park is also home to part of New York’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza.

Coenties Slip today

Nonetheless, these former waterways are a wealth of New York history and culture, and you can still visit many of them today in their new form as city parks. If you want a chance to visit a relic of the original New York, stroll down one of these slips and try to imagine the taste of saltwater on the air, the sounds of the creaking hulls of wooden ships and the snap of partially rolled up canvas sails, the sight of barges and steamships charging into the slips.

Discover more of New York City’s maritime history on an upcoming Untapped Cities Walking Tour!

Tour of NYC’s Maritime History

Get in touch with the author @kellitrapnell.

Subscribe to our newsletter