Play Vintage Games at the Red Hook Pinball Museum

Explore the museum's collection of meticulously restored vintage machines from as early as the 1800s!

Brooklyn Heights is probably best known for its charming, tree-lined streets filled with 19th century mansions and churches. But the bucolic neighborhood boasts more than just cobblestone lanes and scenic views of Lower Manhattan. Being one of the oldest neighborhoods in New York City, it also has its fair share of stories and secrets.

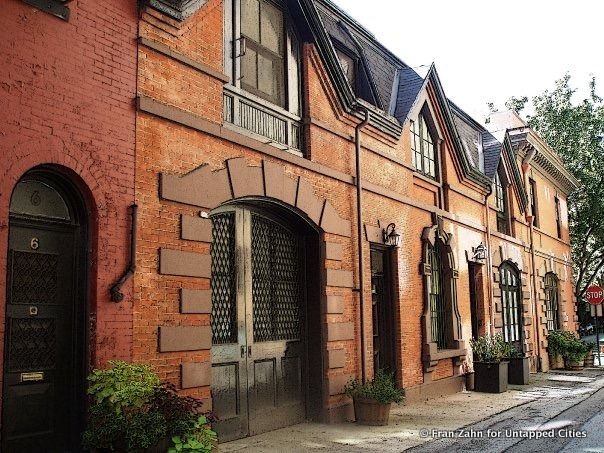

Garden Place, Brooklyn Heights

Brooklyn Heights was a pivotal location in the Revolutionary War. General George Washington stayed at a house on Montague Street before leading the retreat back to Manhattan after the disastrous Battle of Long Island. Around this time, British forces confiscated the Livingston mansion in Brooklyn Heights to be used as a hospital and burial grounds. As a result, reports of Revolutionary-era, British bones being found in the backyards of Garden Place homes have circulated for years.

The St George Hotel, which now houses dormitories for NYU, Pace and other schools, was once the largest hotel in New York City. A large salt water swimming pool could be found in the basement. Remnants of the pool can still be seen in the converted gym there today. The hotel also has a rich musical history as Columbia Records used the ballroom to record songs. The iconic “Rhapsody in Blue” by George Gershwin, among others, was recorded in the hotel. The lobby has since been converted into a subway entrance, one of the quirkier in the city.

A piece of the famous Plymouth Rock resides in the cloister of the Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims on Orange Street in Brooklyn Heights. Henry Ward Beecher, the church’s pastor, was a staunch abolitionist, and helped make the church a stop on the Underground Railroad. Abraham Lincoln’s famous Cooper Union speech was originally slated to take place at Plymouth Church. And though the speech eventually took place across the river, Lincoln still attended services at the church. A statue of The Great Emancipator’s likeness can be seen from Orange Street. See a photo of the Plymouth Rock in Brooklyn Heights and discover where another piece of the rock resides in Brooklyn.

Similarly deceptive is the Häagen-Dazs brand. With a well-placed umlaut, it certainly seems as though the ice cream hails from Scandinavia. However, the frozen dessert is the creation of two Polish immigrants from the Bronx. Furthermore, the letter combinations of “aa” and “zs” do not exist in any Nordic or Scandinavian languages. The original scoop shop exists, however, and can be found on Montague Street.

The ‘house’ at 58 Joralemon Street is actually not a house at all, but rather the world’s only Greek-Revival subway ventilator. The structure also works as an emergency exit for the Lexington Avenue line (4/5) that runs there between the Borough Hall and Bowling Green stops. The facade of red brick and blacked out “windows” blends almost perfectly with the neighborhood’s aesthetic, or at least better than an industrial ventilator would. Read more about this fake townhouse and others here.

Many Brooklyn Heights authors created lasting works here. Parts of “Death of a Salesman”, “Tropic of Cancer”, and “In Cold Blood” were all written in the neighborhood. But one author left an even more concrete legacy, or, better yet, brick and wood legacy. The house on 64 Poplar Street was built in 1834 by a local man with the help of his teenage son, Walt Whitman.

Not surprisingly, Brooklyn Heights has had its share of authors in residence. David McCullough, H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur Miller and W.E.B. Dubois, among several others, have all called the neighborhood home at one point or another. Norman Mailer lived in a few places in Brooklyn Heights. W.H. Auden and Thomas Wolfe lived two doors down from one another. And as Truman Capote, former resident of Willow Street, famously said, “I live in Brooklyn, by choice.”

Photo from inside the now defunct Atlantic Avenue Tunnel. Photo by Vlad Rud via Wikimedia Commons

Photo from inside the now defunct Atlantic Avenue Tunnel. Photo by Vlad Rud via Wikimedia Commons

The Atlantic Avenue Tunnel runs beneath the southern extension of Brooklyn Height’s boundaries from Columbia Place to Boerum Place. Built in 1844, it is believed to be the oldest rail tunnel in North America, and quite possibly the first subway, though the line includes no stations. Originally intended to transport passengers from the heart of Brooklyn to Manhattan-bound ferries at the bottom of Atlantic Avenue, the tunnel has been out of service for over a century. Urban explorer turned tunnel tour guide, Robert Diamond, brought groups to the abandoned tunnel up until 2010. He claims there is also an intact steam engine near Hicks and Atlantic.

Though Brooklyn Heights is known mostly for its charming brownstones and carriage house, there is also a string of 21 buildings, along the neighborhood’s eastern border near Court Street, called the Brooklyn Historic Skyscraper District. In a relatively small area, you can see stunning–and of course very tall–examples of Beaux-Arts, Neo-Romanesque, Neo-Classical, Neo-Gothic, Art Deco and Colonial Revival architecture.

Brooklyn Heights, also known as America’s First Suburb, is the first New York City neighborhood to be added to the National Register of Historic Places. The neighborhood boasts roughly 600 structures built before the Civil War. This wealth of significant architecture – as well as the significant wealth from local residents–helped protect the neighborhood from Robert Moses and his plans to run the Brooklyn Queens Expressway along Hicks Street, effectively cutting the neighborhood in half. The iconic Brooklyn Heights Promenade, with the BQE stacked below, was the compromise between Moses and Brooklyn Heights.

Next, read on for the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central.

Subscribe to our newsletter