One Bryant Park, the first high-rise building to reach LEED Platinum certification ever, is a tower of fun facts. The Durst Organization that built and runs One Bryant Park has not been shy with unique initiatives, like making honey from rooftop bee hives or letting the public control the colors in the spire. For infrastructure nerds, the building also has a co-generation power plant, one of just a few that exist within commercial buildings in New York City and the first to go online back in 2009. We recently had the opportunity to visit the power plant and the bowels of One Bryant Park with Jordan Barowitz, Vice President of Public Affairs at the Durst Organization. “You want to use your energy on the people in the building,” Barowitz tells us, “You don’t want to waste the energy on mechanical systems that are inefficient.”

A co-generation power plant captures waste heat and coverts it into power for heating and cooling. Basically, fuel goes into a gas turbine which is turned into power, but the hot exhaust from the turbine goes into a steam generator which produces power from the exhaust which would normally have gone up in smoke in a traditional power plant. In fact, with traditional coal-fired power plants, about 66% of energy is actually lost as heat upon generation, and an additional 7% is lost en route while being delivered.

Inside the co-generation plant inside One Bryant Park

The Durst Company says its 4.6 megawatt natural gas co-generation power plant is two to three times more efficient than a traditional plant, because it eliminates transmission loss and captures the waste heat. In the winter, this recaptured energy provides heat for the building and the water, and in summer, helps the production of air conditioning. This is all part of an overall effort to use green design to increase the health and productivity of tenants and to reduce the overall environmental footprint of the building. (Buildings overall contribute about 43% of the world’s CO2 emissions).

The plant itself is spotlessly clean and you need hard hats to enter. Outside the doors, a sense of humor still pervades: “Meet the person most responsible for your safety” reads a sign on top of a mirror. Still, the safety measures are numerous, including an exterior wall that is designed so that it can blow out into the open space above a green roof terrace on the sixth floor in case of an issue.

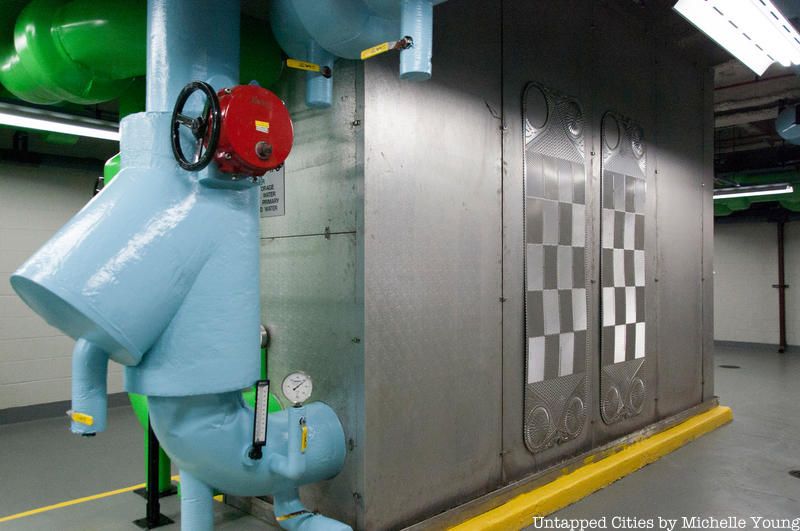

About 40 ice storage tanks are part of a system that cools the building

Examples of the heat plates are affixed to the outside of the ice storage heat exchanger

One room in the basement is host to electrical centrifugal chillers, large industrial versions of a window box air conditioner, Barowitz explains to use in layman’s terms. The chillers are in different sizes — “they run at maximize efficiency when they run at maximum capacity” says Barowitz, and that the building will use different chillers depending on the demand in the building.In the evening, very cold glycol enters one of about forty ice tanks that are filled with miles of rubber tubing. During day time, the glycol goes through a plate frame heat exchanger, located next to the tanks, which cools the water which is then piped through the building as air conditioner.

Three of the electric centrifugal chillers

Air vents from the floors can be opened or closed to control temperature

All of the activity is monitored on a big digital screen which shows not only all the relevant data on the chillers, ice storage tanks, and co-generation plant, but also exactly what is happening on each floor from CO2 levels to temperature and other metrics. When CO2 levels get too high, Barowitz says, people get sleepy, and denser floors will create higher levels of carbon dioxide.

The beehives on One Bryant Park

To the Durst Organization, “Green means business,” and One Bryant Park is its showcase example of how sustainability and the bottom line can operate in tandem. Other institutions have also found that the high initial investment pays off. NYU’s 13.4 megawatt cogeneration plant, located under the plaza of the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, kept humming while the rest of Lower Manhattan was knocked out of power during Hurricane Sandy. Cooper Union’s first co-generation plant at 41 Cooper Square was so successful that it built a second one on its landmarked Foundation Building. Size of building has also not been a major limiting factor, with the configuration of cogeneration plants using microturbines, such as the ones installed at residential buildings like Tribeca Green and Millennium Tower. Like most things sustainable, it takes a long time for ideas to become mainstream but buildings like One Bryant Park are leading the way.

Next, check out 10 exciting sustainable energy projects in NYC.