NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

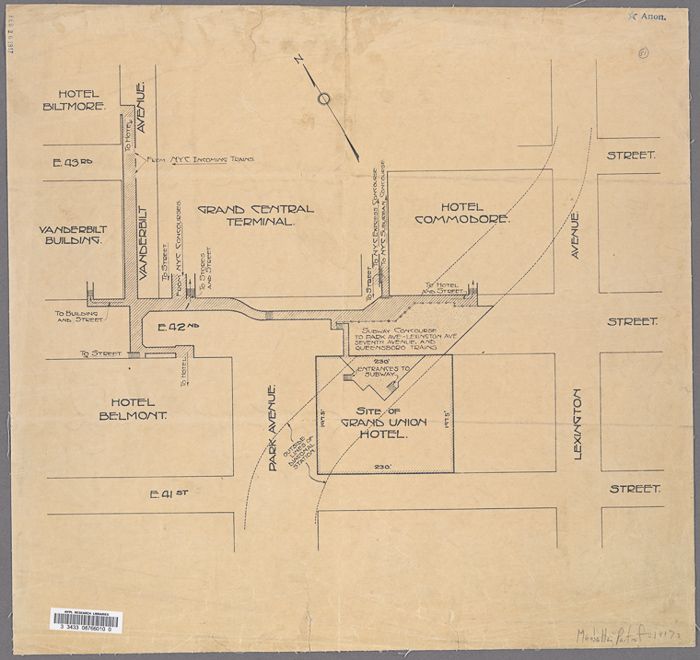

For decades, wealthy visitors to New York City stayed at renowned hotels like the Roosevelt, Waldorf-Astoria and Biltmore due to their proximity to the major shopping and entertainment destinations. Whereas now visitors must take a cab or walk from the transportation hub, Grand Central Terminal used to have underground tunnels connecting to various buildings nearby, including hotels and offices. As part of an underground network called Terminal City built in the early 1900s, many of these tunnels were constructed to better connect New York.

While many of these tunnels have since been demolished, a handful still stand in all their glory, while some contain just a few artifacts and remain still accessible today. Check out these eight historic (and modern) tunnels at Grand Central Terminal!

From hidden tennis courts to the remnants of a lost movie theater and an office-turned-speakeasy, uncover the secrets of New York City's iconic train terminal!

There is a secret passageway below The Roosevelt Hotel that once connected it to Grand Central Terminal. While the hotel side of this tunnel has long been closed off, the other side, which emerged into Grand Central, had been forgotten but rediscovered. Reed & Stem, accompanied by engineer William W. Wilgus, began designing a network of hotels and office buildings called Terminal City in 1902 with the intention of creating a commercial center that stretched the length of Park Avenue. The hotel, which opened in 1924, was part of the second phase of Terminal City’s construction between 1920 and 1931 and included such buildings as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the Graybar Building and 277 Park Avenue.

There are currently locked doors inside Grand Central that lead to the lost tunnel to the Roosevelt Hotel. It continued to run north under Vanderbilt Avenue until there was access to The Roosevelt Hotel’s basement. Within The Roosevelt Hotel, there are two potential known entrances into the tunnels: one closed-off portion was once accessed “to the side of the hotel’s lobby,” and one down a staircase via the shopping corridor one level below the lobby.

Like the Roosevelt Hotel, the Biltmore Hotel also featured a tunnel connecting it with Grand Central. One of the Biltmore Hotel’s best amenities was the ease with which guests could come and go using the hotel’s connection to the terminal; guests of the Biltmore would have their luggage collected from the train by porters, and they would then travel via tunnel to an elevator in the hotel’s basement and be carried up into the hotel without ever having to step outside.

The hotel was stripped down to its steel skeleton in the 1980s, and all that is left of the original structure are small remnants like a passageway and an iconic golden clock. The passageway is notable for featuring Guastavino tile work with an arched herringbone pattern, which is found at dozens of other locations throughout the city. The “Tile Arch System” is one of 24 patents that the Guastavino father and son team devised over time while running the family business. The technique is used to create vaulted arches that consist of layered terra cotta tiles arranged in a zig-zag, most often, herringbone pattern and sealed with specialized cement.

The abandoned Track 61 at Grand Central Terminal has a storied history full of clandestine government movements and illicit affairs, at least according to city legend. Untapped New York busted perhaps the biggest myth of Track 61, the story that the abandoned train car that sat on the track for decades belonged to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, However, there is some truth to other legends. Track 61 and Track 63 were originally built to carry freight and serve as loading platforms for a nearby steam powerhouse that served Grand Central. When the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel purchased the air rights above these tracks in 1929, it also acquired the track below, and the steam powerhouse was subsequently knocked down. A New York Times article from September of that year announced that the hotel would feature “a private railway siding underneath the building,” where “guests with private rail cars could have them routed directly to the hotel.”

The first person to reportedly make use of this private station was General John J. Pershing in 1938, who would proceed into an elevator and make his way into the hotel; it is unclear whether the elevator led directly into the hotel, though. And although the Roosevelt train car myth has been debunked, there is one documented occasion on which President Roosevelt made use of Track 61. On October 21, 1944, Roosevelt made a campaign stop in New York City. A Secret Service memorandum states, “At 10:05 p.m., the President will leave the hotel over the same route he entered, i.e., via east side Lexington Avenue elevator, and will then proceed via New York Central elevators to the New York Central Rail[road] siding, located in the basement of the hotel.” Every U.S. President from Herbert Hoover to Barack Obama has stayed in the Waldorf-Astoria’s presidential suite. According to an article in The New York Post, the track was likely used as an “escape option” by the Secret Service for President George W. Bush, Secretary of State Colin Powell, and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice in 2003 while in meetings for the U.N. General Assembly.

Another forgotten underground passageway was built under 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, the Vanderbilt Concourse building (also known as the Manhattan Savings Bank Building) between 44th and 45th Street. The Manhattan Savings Bank was the key tenant of the building with a branch on the ground floor. The tunnel is still accessible by entering through double wooden doors on 45th Street just off Vanderbilt Avenue, with a glass transom window that says “Grand Central Terminal.”

The tunnel runs south for a short stretch, turns east, and hits the 45th Street Passage inside Grand Central. The tunnel includes Manhattan Savings Bank drop boxes, now repurposed as advertising frames. There is also a graffiti mural with the word “love” repeated over and over by street artist Chris Riggs.

Last year, a long-shuttered tunnel connecting Grand Central to the Socony-Mobil Building reopened to the public The reopening and renovation of this subterranean pedestrian pathway was part of a $220 million transit improvement project completed in conjunction with the construction of One Vanderbilt. Now a New York City Landmark, the Socony-Mobil building at 150 E. 42nd Street was built between 1954 and 1956. The tunnel was completed in 1955 and appears to have closed in 1991. According to a New York Times article, the 215-foot route starts “twenty feet inside the new skyscraper,” then “bends northwest from the southeast corner of Lexington and 42nd Street to a point a little south of center in Forty Second.” It then continued west for 120 feet where it met the Chanin Building passageway then bent toward the Commodore Hotel, now the Grand Hyatt.

Construction of the passageway was rather challenging since work was complicated by the busy streets above and the mess of utilities underground. A water main that stretched directly across the tunnel’s path had to be looped over the passageway’s roof. Workers also had to carefully avoid telephone wires, mail tubes, gas mains, and power cables. The reopening of this historic passageway comes with the addition of two street-level subway entrances and a new entrance to the 42 Street subway station on the southeast corner of 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue.

Underneath Grand Central used to be a trolley loop built in the 1890s under the direction of William Steinway, owner of the piano company which still exists in Astoria, Queens. The tunnels made only a handful of trips in the early 1900s before the tracks were sold to the city, and a large part has been left abandoned.

After the death of William Steinway, August Belmont, the founder of the Belmont Stakes, took the lead on the tunnel project. This came after an accidental explosion in December 1982 that killed five workers, as well as the disastrous Panic of 1893. Because the trolley enterprise was entirely privately run, Belmont was never granted a franchise to operate the line, leading him to sell the tunnels to the city. The tunnels were converted to rapid transit tunnels, and they were expanded after the rapid transit cars had difficulty making tight turns. One segment of the loop was later repurposed as a pump room.

Deep below Grand Central Terminal is a hidden power station known as M42. The original converters, which are no longer in operation, powered much of the New York Central Railroad and were said to be a target for German spies who wanted to sabotage rail movement on the East Coast. While there were spies in America focused on destroying infrastructure, there is no contemporary evidence as of yet that Grand Central, or the M42 basement specifically, was a target. In the book Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America, writer Sam Roberts offers that Grand Central could have been a target but as I Ride the Harlem Line documents, neither the reports from MI5 or first-hand accounts by the spy ring’s own members mention it.

Still, M42 was part of the shift from steam-powered locomotives to electrified rail. This shift occurred following a horrific accident in the Park Avenue tunnel in 1902; steam blocked sightlines in the tunnel out of Grand Central and caused an express train from White Plains and a commuter train to collide under 56th Street. Steam trains were banned in Manhattan starting in 1908 six years after the deadly incident. Third rail power was produced by a steam station on Park Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, which was later demolished both because residents had come to see it as an “eyesore” and because a sale of the increasingly valuable land and air rights was needed to fund the new Grand Central Terminal.

From hidden tennis courts to the remnants of a lost movie theater and an office-turned-speakeasy, uncover the secrets of New York City's iconic train terminal!

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal!

Subscribe to our newsletter